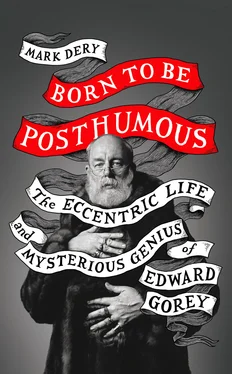

Outside the classroom, however, he floored the accelerator. Harvard is where Gorey perfected his image, stylizing his zany fashion sense and theatrical mannerisms into the persona that, with a few last tweaks (pierced ears, copious necklaces, sidewalk-sweeping fur coats dyed heart-attack green or yellow), would turn heads in Manhattan. More important, Harvard is where he sketched in the intellectual substance of his eccentric persona, drawing inspiration from writers like Firbank and Compton-Burnett. From Lear, he took the limerick form. Encouraged by Ciardi, he put to drily amusing use a mock-moralistic tone that parodied Victorian writing for children. Even the melancholy epitaphs at Mount Auburn Cemetery, mementos of the Victorian cult of mourning, and the Puritan reproaches to mortal vanity in the Old Burying Ground near Harvard Square had something to teach him: their lugubrious cadences and morbid sentiments, so melodramatic they verge on black comedy, echo in Gorey’s verse.

He learned as much from his antipathies as he did from his sympathies: in several interviews, he returned to a subject dear to his heart, his adamantine hatred of Henry James, whose tendency to explain things to death he found wearisome, whose labyrinthine sentences maddened him, and whose characters he found morally repugnant, motivated by “utterly unpleasant arid curiosity.” 103In an essay for a comp lit class, he wrote, “James’s favoured method of unfolding an action is to have it revealed, slowly, bit by bit, through inexhaustible questionings, probings, pryings, comparings on the part of onlookers of the main action…. If anyone ever literally died of curiosity I am certain it must have been a Jamesian character.”

Crucially, he discovered that he wasn’t a novelist but that he might, by combining his gifts for narrative compression and epigrammatic wit with his meticulous, hand-drawn engravings, produce masterpieces of miniaturism that defy categorization. All the while, he was evolving as an artist, polishing his draftsmanship and, through his exploration of watercolor, developing a taste for subtle color harmonies and deliciously queasy hues.

But when it came to Gorey’s maturation as an artist and a thinker, nothing in his four years at Harvard affected him more profoundly than his relationship with Frank O’Hara. Their friendship introduced both men to new interests and influences; each sharpened his ideas about art, literature, music, film, theater, and ballet on the whetstone of the other’s equally nimble, wide-ranging mind. Postmodernists avant la lettre , they embraced lowbrow, highbrow, and middlebrow tastes with gusto and without apology.

As important, each was present at the birth of the other’s self-creation and, consciously or not, lent a hand. “All of us were obsessed ,” Gorey later recalled, characterizing the mood of their Harvard years. “Obsessed by what? Ourselves, I expect.” 104The bearded dandy nerd in Keds and fur coat, fingers dripping rings, was “a kind of this-is-me-but-it’s-not-me thing,” Gorey later confided. 105Meaning: “Part of me is genuinely eccentric, part of me is a bit of a put-on.” 106He added, slyly, “But I know what I’m doing.” (Another time, he struck a more poignant note, seeming almost trapped by his eccentric image: “I look like a real person, but underneath I am not real at all. It’s just a fake persona.”) 107

Though Gorey and O’Hara crossed paths briefly after graduation through their involvement with the Poets’ Theatre, in Cambridge, their friendship wouldn’t survive long. After both men moved to Manhattan—O’Hara in ’51, Gorey in ’53—their lives intersected only occasionally, though they frequented the New York City Ballet, had friends in common, and lived just a subway stop apart.

Their diverging trajectories had something to do with it. In New York, O’Hara’s engagement with contemporary art would draw him into the orbit of the abstract expressionists, whose frenetic socializing and improvisatory aesthetic would show him the way out of naturalism’s imitation of life and into a poetry collaged out of scraps of life itself—snatches of conversation, things seen and freeze-framed by his camera eye, quotations from his encyclopedic reading and movie watching and gallery going. O’Hara was addicted to the Now—to art forms such as action painting, which captured “the present rather than the past, the present in all its chaotic splendor,” writes Marjorie Perloff in Frank O’Hara: Poet Among Painters . 108

Gorey, by contrast, immersed himself ever deeper in things past—silent movies, Victorian novels, Edward Lear, the Ballets Russes. Pursuing his solitary obsessions, he chased a vision all his own, wholly new yet sepia-tinted with a sense of lost time. *O’Hara was avant-garde; Gorey was avant-retro. At Harvard, Gorey distilled his influences into a concentrated essence that would nourish his art for the rest of his life. O’Hara, by the summer of ’49, was shaking off his Firbankian affectations. Critiquing a friend’s poem, he wrote, with mock condescension, “I can see certain tendencies in you which we all have to get rid of. With me it was Ronald Firbank, with you it looks a bit like the divine Oscar …” 109

Their friendship came to grief over one of O’Hara’s pointed wisecracks. Maybe there had always been a little rivalry beneath their sharp-witted jousting—who knows? But O’Hara’s hipster derision at Gorey’s Firbankian sensibility—so arch, so preciously aesthetic, so aloof from the cultural ferment of the moment—emerged undisguised in a jab that cut too close to the bone. “Ted told me that he’d seen Frank at some point shortly after he’d moved to New York,” Larry Osgood remembers, “and Frank’s opening remark, practically, was, ‘So, are you still drawing those funny little men?’ And Ted took great offense at that, and that was that for that relationship.”

Years later, Gorey settled the score. Rolling his eyes at the idea that his former roommate, who banged out his poems on the fly, was some kind of genius, he told an interviewer, “I was astonished after his death, and even before, when he became a kind of icon for a whole generation. If you know somebody really well, you can never really believe how talented they are. I know how he wrote some of those poems, so I can’t take them all that seriously.” 110

O’Hara died in 1966, at the age of forty, killed by a teenager joyriding at night in a Jeep on the beach at Fire Island. At Harvard, in the first flush of their friendship, he’d written a poem for Ted that was later included in his posthumous collection, Early Writing . Titled, simply, “For Edward Gorey,” it evokes not only the Victorian-Edwardian setting of Gorey’s work and its insular, dollhouse psychology but also the sense of the Freudian repressed that haunts it. Referring to the “anger” underlying Gorey’s “fight for order,” he notes, “you people this heatless square / with your elegant indifferent / and your busy leisured / characters who yet refuse despite surrounding flames / to be demons.” 111He evokes the taxidermy stillness of Gorey’s vitrine worlds (“You arrange on paper life stiller than / oiled fruits or wired twigs”) and the obsessive cross-hatching that is a Gorey signature (“See how upon the virgin grain / a crosshatch claws a patch / of black blood …”).

Strangely, in O’Hara’s spyhole view of Ted’s world, Gorey’s funny little men are female: “You transfigure hens, your men cluck tremulous, detached …” Is this a coded reference to their gay circle at a time when it was common for gay men, among themselves, to jokingly adopt women’s names? The poem ends on a moody, crepuscular note, wonderfully evocative of the perpetual twilight in which Gorey’s stories always seem to take place: “And when the sun goes down,” O’Hara writes, the hen-men’s “eyes glow gas jets / and the gramophone supplies them, / resting, soft-tuned squawks.”

Читать дальше