Aged twenty-three, pregnant with Alexander and ruling over a country that had just lost its king and a huge number of men, all at the hands of her brother and sister-in-law, Margaret’s role as regent must have seemed fraught with difficulty. A pro-French faction took shape at Parliament, urging that Margaret be replaced by the French-born uncle of James V, John Stewart, Duke of Albany. For just over a year, she deftly managed to fend off the rival factions around her whilst maintaining a tenuous peace with her home country. In seeking allies, however, she would end up making the mistake of falling for the pro-England Archibald Douglas, Earl of Angus (described by his own uncle as a ‘young, witless fool’), whom she secretly married. In doing so, she forfeited the regency and Parliament appointed the Duke of Albany in her stead in September 1514. Margaret headed to Stirling Castle, where she was forced to hand her two sons over into the care of their uncle.

Now pregnant with the Earl of Angus’s child, she escaped to England, and in Harbottle Castle in Northumberland she gave birth to Margaret Douglas; two months later, in December 1515, she learned of the death of her second son, Alexander. Angus, showing his true colours, fled back to Scotland, leaving Margaret to head to the protection of her brother Henry in London. She returned to Scotland in 1517 to discover that Angus had rekindled a relationship with Lady Jane Stewart, with whom he’d had an illegitimate child, all the while living on Margaret’s dower income. Margaret was rightly outraged and mooted divorce to her brother, although Henry was opposed to it (which was a bit rich coming from him), and in angered response Margaret allied herself more closely with the Albany faction.

The Duke of Albany, who had been in France for three years, returned to Scotland in November 1521 and both he and Margaret actively sided against Angus. This lasted until 1524, when Margaret organised a coup d’état and ousted Albany, restoring twelve-year-old James to the throne, with Margaret formally recognised as the chief councillor to the King. Still desperately wanting a divorce from Angus, she ordered cannon guns to fire on him when he appeared in Edinburgh with a large group of armed men. Angus (sadly) managed to dodge the cannon balls and ended up in control of the King, whom he kept a virtual prisoner for three years.

In 1527, Margaret was finally granted a divorce by the Pope, after which she married a member of her household, Henry Stewart, later titled Lord Methven. When James assumed the full role as King in 1528, Margaret and Methven would act as close advisors to him, although by 1534 she fell out of favour with her son when she was discovered betraying state secrets to her brother, Henry. All was not well with her marriage either, as Methven proved equally partial to cavorting with other women and spending Margaret’s money. She would eventually reconcile with Methven and in 1538 form a close bond with her new daughter-in-law, the French queen consort of James V, Marie de Guise, before dying of a stroke in 1541 at Methven Castle in Perthshire.

Margaret Tudor’s tenure as Scottish Queen was turbulent and her life was made all the more difficult by the loss of James IV and her subsequent marriages to unscrupulous men. Throughout it all she tried to bring about a better understanding between long-time enemies England and Scotland, and no doubt would have whooped with delight at the eventual union of the Scottish and English crowns under her great-grandson, King James VI and I.

Born: circa 1048

Died: 1138

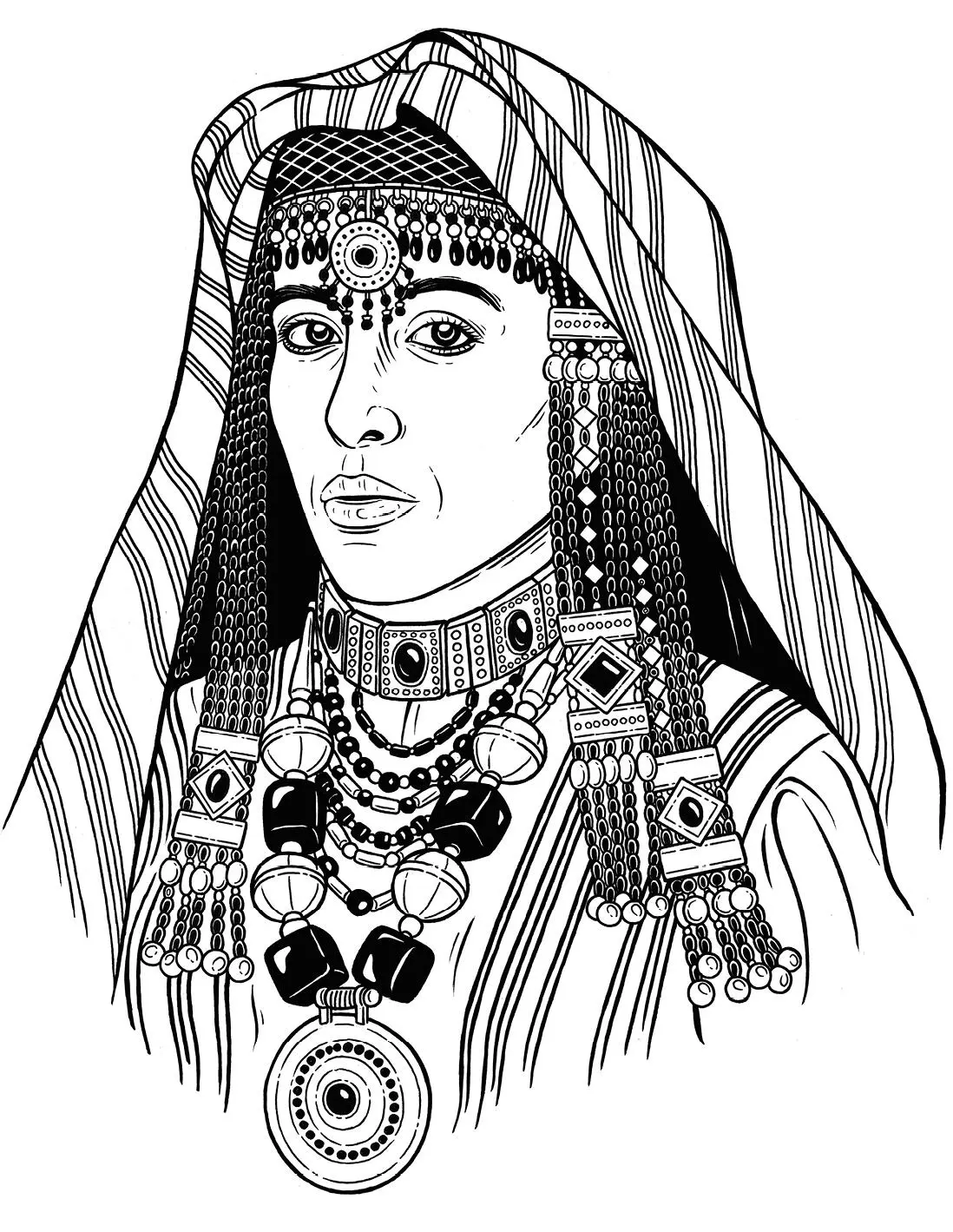

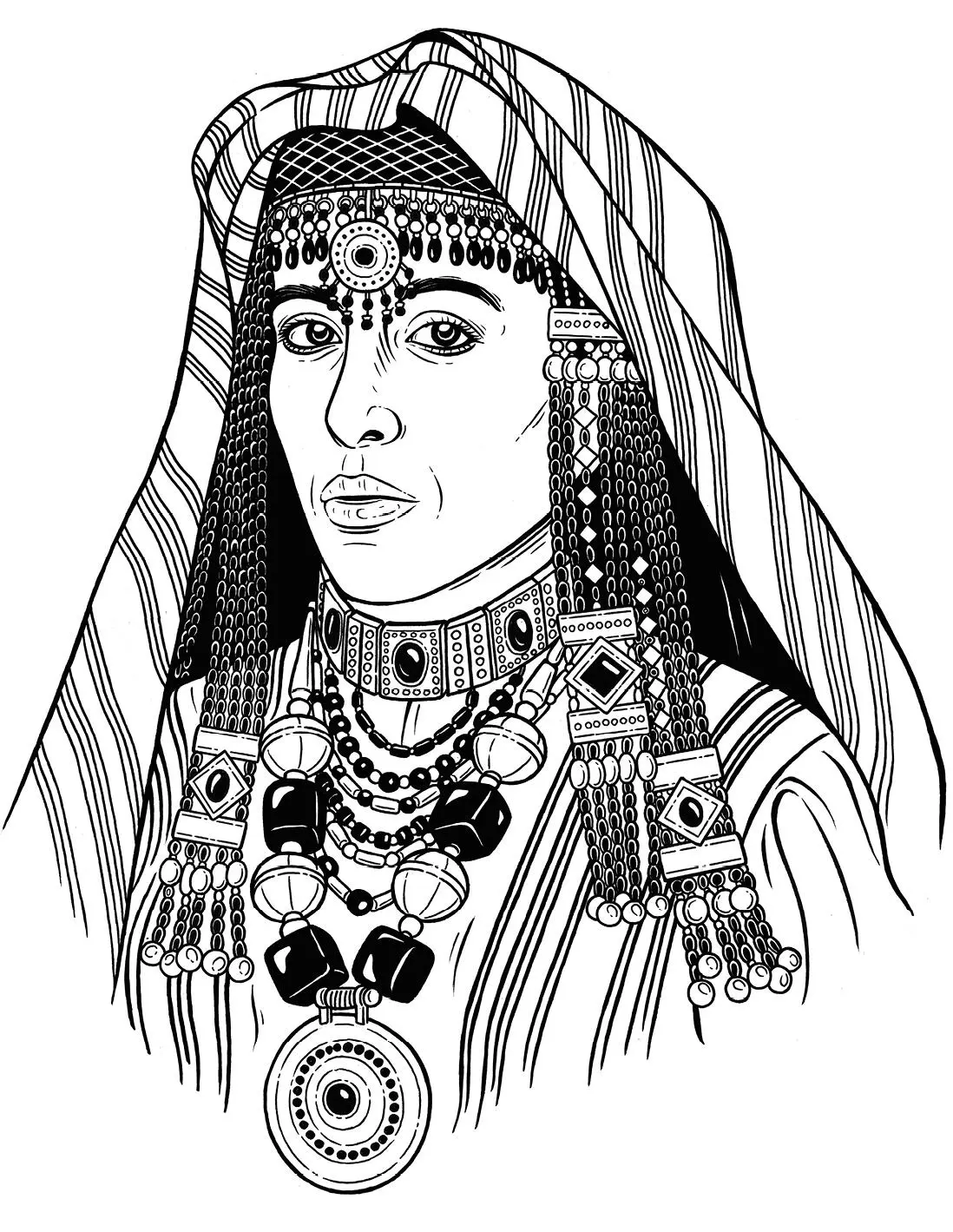

Arwa al-Sulayhi was a long-reigning and powerful queen of Yemen. She was affectionally called by her many supporters the ‘Little Queen of Sheba’, as some claimed her throne was even greater than the biblical Queen of Sheba, who was thought to rule the kingdom of Saba in Yemen. She and her aunt before her were respected as sovereign rulers of the Sulayhid dynasty, and for the first time in Arab-Muslim history khutba prayers in mosques were proclaimed in their names, a privilege traditionally given only to monarchs. Arwa occupies a unique place in Islamic history, not only because she was a female ruler but also because her reign brought prosperity and stability to Yemen. And yet few know of her rule or even her name, her memory consigned to that now hefty file of forgotten queens.

Orphaned at a very young age, Arwa was brought up by her uncle, Ali al-Sulayhi, the then ruler of Yemen, and her aunt, Asma bint Shihab, in the palace of the Yemeni capital Sana’a. Ali, who had ruled since 1047, had named Asma ‘ malika ’ (queen) and formally acknowledged her as co-ruler, and her name was proclaimed in mosques alongside her husbands in the khutba . As a result, Asma attended council meetings and the King regularly sought her counsel and consulted with her over state business. Growing up alongside her cousin, Ahmad-al Mukarram, Arwa was groomed to be Queen. At the age of seventeen, she married al-Mukarram (cousins as marital partners are a popular choice for royal families wherever you are in the world). The bride received the principality of Aden as her dowry, after which she took charge of its management, appointing governors and overseeing collection of its taxes.

In 1067, King Ali and Queen Asma took a pilgrimage to Mecca. On the way there, their large caravan stopped for a night at an oasis. Suddenly they were attacked by their Ethiopian enemy, Sa’id ibn Najah, the Prince of Zabid. Ali was killed, his 5,000 accompanying soldiers were persuaded to join Sai’id, and Asma was taken to a secret prison in Zabid. There, it was said that the severed head of the King was placed on a pole where his widow could see it from her cell. After a year’s imprisonment, Asma managed to get a message to al-Mukarram. Notables in Sana’a immediately rallied in support of al-Mukarram ‘to save the honour of the Queen’. Three thousand horsemen rode to Zabid and succeeded in routing the 20,000 Ethiopians defending the city, and al-Mukarram rushed to the prison where his mother was being held.

Still wearing his helmet, he arrived at the door of Asma’s cell, announced who he was and asked if he could enter. With his face masked, however, the Queen was suspicious and it was only when he took his helmet off that she could see it was her son and immediately greeted him as the King. It was said that al-Mukarram was so shocked, both at seeing his mother alive and being named as King, that he suffered partial and permanent paralysis.

Both mother and son returned to Sana’a, al-Mukarram was invested as King but Asma acted as the effective regent as al-Mukarram was now largely bed-ridden. Asma also brought in her aunt Arwa to help with affairs of state, which she did for another two decades. In 1087, Asma died, al-Mukarram had largely removed himself from public life and Arwa was acknowledged as co-regent. She became known as Sayyida-al Hurra (meaning ‘noble queen’) – the same title given to another much-admired Moroccan queen of the 1500s (see Sayyida al-Hurra).

As ruler, Arwa set upon reasserting the might of the Sulayhid dynasty and to avenge her father-in-law’s death. She moved the capital from Sana’a to the mountainous fortress city of Jabala, installing al-Mukarram there along with her treasure. Near to Jabala she managed to crush the army of Sa’id ibn Najah, having lured their leader to Jabala under the pretext that her allies were about to abandon her, whereas they were in fact lying in wait for the Ethiopians. Sai’d was killed and his wife Umm al-Mu’arik was imprisoned. Arwa then ordered that Sai’d’s decapitated head be placed on a pole just outside his wife’s cell, mirroring the punishment meted out to her aunt and uncle – proving that queens can be just as vindictive as their male counterparts.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)