It was splendid – and yet, Sophie knew that if the sightseers were to venture the full length of the long street, they would find it changed entirely. By the time they reached its opposite end, the magical grandeur would have melted away like a dream. The shops and palaces would be replaced by ramshackle tenements; the elegant people by ordinary working folk in old shawls and big aprons, or muddy sheepskins; an old man selling roasted pumpkin seeds from a brazier, and beggars huddling out of the cold.

Just like London, St Petersburg had two different faces – and during the six weeks she had been here, Sophie had made it her business to get to know them both. She knew most English people in the city stayed away from its darker corners, remaining safe in their own comfortable circle – socialising at the New English Club, shopping at the Magasin Anglais, and barely understanding a word of Russian. But Sophie wanted to know the real St Petersburg. She’d spent hours walking around the city streets until her feet ached; and had persuaded Vera’s son, Mitya, to begin teaching her to speak Russian herself.

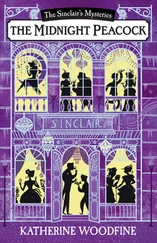

Today however, no Russian would be required. Sophie’s destination was on the most splendid section of the Nevsky. Beneath the sign of the Imperial Eagle, gold letters spelled out in both English and French: Rivière’s Jewellery & Fine Goods . Some of the sightseers had paused to admire the sumptuous façade, and to peep into the arched windows, through which it was possible to glimpse St Petersburg’s elite, lingering over glass-fronted cabinets. Inside them, a treasure trove of exquisite objects glittered like a fairy hoard.

Rivière’s was a maker of marvels and dreams. There were twinkling crystal flowers fit for an enchanted garden; tiny jewelled scent bottles, no bigger than Sophie’s thumb; and little gold tea sets that the Tsar’s daughters used for their tea parties. There were jewel boxes no bigger than a bird’s egg, and diamond brooches that glittered like frost. There were miniature animals, carved from precious stones, which Nakamura said made him think of the Japanese sculptures called netsuke – a carnelian fox with eyes of rubies, a crystal rabbit, a jade frog with a single pearl in its mouth.

But what Rivière’s was really famous for was its music boxes. Each year, Monsieur Rivière himself designed a new music box for the Tsar to give to his children at the New Year festivities. Each music box was extraordinary – from a silver-gilt castle, with jewelled flags flying, to a moving carousel, complete with golden horses. Keen to follow the Imperial family in everything, St Petersburg’s wealthy flocked to Rivière’s to purchase music boxes of their own. Sophie’s favourites were all in the shape of birds – a green parrot in a gilded cage, a wonderful peacock with a jewelled tail, and a magnificent golden firebird, decorated with gleaming rubies. They reminded her very much of a music box which had been made here in this very shop: the Clockwork Sparrow.

In a strange way, she thought, as she made her way behind the shop towards the staff entrance, it was the Clockwork Sparrow that had brought her here. It had certainly helped her get this job at Riviere’s: when she’d explained she had worked at Sinclair’s, London’s finest department store, for the famous Mr Edward Sinclair, himself a great collector of Rivière’s objects, and when she had talked of his marvellous Clockwork Sparrow, she had been hired almost at once. Of course, it helped that she spoke French – the language of St Petersburg’s aristocrats, who considered Russian the language of the peasants. And being English was a distinct advantage too: for in Russia, her new colleague Irina had explained to her, any English person was automatically considered someone of importance – even a ‘milord’ or ‘milady’.

Now, she pushed open the door and went through into the workshop at the back of the shop. No one even glanced up at her – except for Boris, one of the master jewellers, and Vera’s husband – who gave her a quick, kindly smile from where he was already hard at work examining some technical drawings that were spread out on the workbench before him.

Sophie was quite used to that. In Rivière’s workshop, there was always a feeling of intense concentration in the air. The only sounds to be heard were the scrape of a stool on the floor, the clink of a delicate jeweller’s instrument, or the occasional brief mutter in any one of a dozen languages – for Rivière’s artisans came from all over Europe. With protective smocks over their clothing, the jewellers bent low over their workbenches, holding tiny paintbrushes or magnifiers in their hands – whilst behind them, polished wooden shelves stretched from floor to ceiling, each filled with miniature objects, glinting with precious stones or bright with enamel designs.

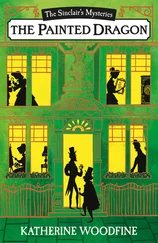

Sophie slipped quietly past, towards the cloakroom. She found herself thinking, as she often did, of how strange it was that the Clockwork Sparrow had been made here in this very room. How peculiar it was that so much could have come from something so small – a tiny mechanical bird she could hold in the palm of her hand! For if the Clockwork Sparrow had never existed and been stolen, she might never have discovered her talent for detective work; Taylor & Rose might never have existed; she might never have known about the Baron and his secret society, the Fraternitas Draconum . And of course, if it were not for the Fraternitas she wouldn’t be in St Petersburg at all.

She’d come here on the trail of a notebook which the Fraternitas had stolen: a most important notebook that contained research about the sinister society itself, but more significantly, information about a powerful secret weapon they had hidden away centuries ago. They had concealed clues to the weapon’s location in Benedetto Casselli’s dragon paintings, so that future members of the society could find it. The notebook contained information about how the clues in the paintings could be ‘decoded’ to locate the weapon: but if the Fraternitas were to get hold of it, Sophie knew they would use it to help spark off a terrible war in Europe. It was down to her to get the notebook – and prevent them.

Somewhere, she mused, as she went into the cloakroom to hang up her coat and tidy her hair, in some other world, there was no Clockwork Sparrow. In that world, there was a Sophie who had never come here, who didn’t think at all about things like secret weapons, or wars, or shadowy societies. Perhaps that Sophie was still selling hats at Sinclair’s, gazing out of the window at Piccadilly Circus, and looking forward to going out to tea with Lil.

It was a cosy thought, yet at the same time it made her feel strangely uncomfortable. Her old life seemed small and restricted – a little box into which she would no longer be able to contain herself. Now, she was a thousand miles from London and Piccadilly Circus. And yet at the same time, Rivière’s was oddly like Sinclair’s, she mused, as she went through into the shop, where sales assistants in white gloves moved quietly to and fro. There was the same sumptuously thick carpet; the same richly polished wood and velvet; the same aroma of beeswax, and perfume, and luxury. The Russian countesses admiring jewels could so easily be London ladies, excited about a new Paris hat.

The shop manager gave her a quick nod, gesturing towards a group gathered around a display of diamond bracelets. Sophie went over to them at once: ‘ Bonjour, mesdames ,’ she began. ‘May I be of any help?’

But even as she showed them the bracelets, Sophie kept a sharp eye out. There was someone she was looking for amidst the silk top hats and frothy ostrich feathers – one person she wanted to see, more than anyone else.

Читать дальше