EGMONT PRESS: ETHICAL PUBLISHING

Egmont Press is about turning writers into successful authors and children into passionate readers – producing books that enrich and entertain. As a responsible children’s publisher, we go even further, considering the world in which our consumers are growing up.

Safety First

Naturally, all of our books meet legal safety requirements. But we go further than this; every book with play value is tested to the highest standards – if it fails, it’s back to the drawing-board.

Made Fairly

We are working to ensure that the workers involved in our supply chain – the people that make our books – are treated with fairness and respect.

Responsible Forestry

We are committed to ensuring all our papers come from environmentally and socially responsible forest sources.

For more information, please visit our website at www.egmont.co.uk/ethicalpublishing

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is an international, non-governmental organisation dedicated to promoting responsible management of the world’s forests. FSC operates a system of forest certification and product labelling that allows consumers to identify wood and wood-based products from well-managed forests.

For more information about the FSC, please visit their website at www.fsc-uk.org

Also by Michael Morpurgo

Arthur: High King of Britain

Escape from Shangri-La

Friend or Foe

The Ghost of Grania O’Malley

Kensuke’s Kingdom

King of the Cloud Forests

Little Foxes

Long Way Home

Mr Nobody’s Eyes

My Friend Walter

The Nine Lives of Montezuma

The Sandman and the Turtles

The Sleeping Sword

Twist of Gold

Waiting for Anya

War Horse

The War of Jenkins’ Ear

The White Horse of Zennor

Why the Whales Came

The Wreck of Zanzibar

For Younger Readers

Conker

Mairi’s Mermaid

The Best Christmas Present in the World

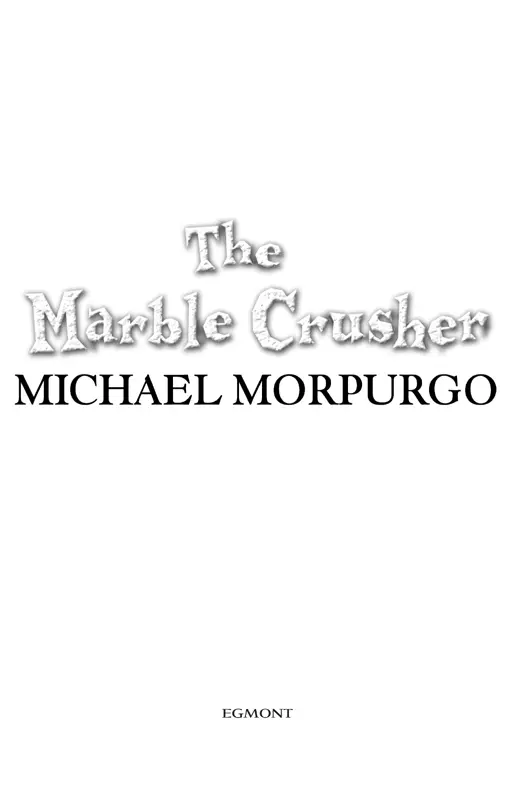

First published in Great Britain as three separate volumes: The Marble Crusher published 1992 by William Heinemann Ltd Text copyright © 1992 Michael Morpurgo

CONTENTS

THE MARBLE CRUSHER THE MARBLE CRUSHER CHAPTER ONE ALBERT WAS TEN YEARS OLD. HE WAS A quiet, gentle sort of a boy with a thatch of stiff hair that he twiddled when he was nervous. He had moved to town from the countryside. ‘We have to go where the work is,’ his mother had told him, and there was work in the town. So Albert came from his little village school to a new school, a school which was noisy and full of strange faces. The other children called him Bert, or Herbert, neither of which was his name. They kept asking him questions and they wouldn’t leave him alone. There was somewhere to get away from it all, behind the bike shed in the playground, but never for long. By the end of each day Albert felt like a sponge squeezed dry. He smiled so much that it hurt. He tried to laugh at everyone’s jokes, and he believed everything they told him. He was naturally a trusting child, and now, in the first weeks of his new school, he wanted to please everyone, to make friends. They teased Albert of course, and he was easy enough to tease, but Albert just smiled through it all. They called him ‘Twiddler!’ and Albert smiled and went on twiddling his hair. He did not seem to mind. It was Sid Creedy who discovered that Albert would believe almost anything he told him. They were playing football in the playground in break when Sid turned to his friends and said, ‘Watch this.’ He dribbled the ball over towards Albert, and his friends followed him. ‘My dad,’ said Sid, ‘he played centre-forward for Liverpool. Did for years. Then they asked him to play for England, but he didn’t want to – he didn’t like the colour of the shirt.’

COLLY’S BARN

CONKER

THE MARBLE CRUSHER

CHAPTER ONE

ALBERT WAS TEN YEARS OLD. HE WAS A quiet, gentle sort of a boy with a thatch of stiff hair that he twiddled when he was nervous.

He had moved to town from the countryside. ‘We have to go where the work is,’ his mother had told him, and there was work in the town.

So Albert came from his little village school to a new school, a school which was noisy and full of strange faces. The other children called him Bert, or Herbert, neither of which was his name. They kept asking him questions and they wouldn’t leave him alone.

There was somewhere to get away from it all, behind the bike shed in the playground, but never for long. By the end of each day Albert felt like a sponge squeezed dry. He smiled so much that it hurt. He tried to laugh at everyone’s jokes, and he believed everything they told him. He was naturally a trusting child, and now, in the first weeks of his new school, he wanted to please everyone, to make friends.

They teased Albert of course, and he was easy enough to tease, but Albert just smiled through it all. They called him ‘Twiddler!’ and Albert smiled and went on twiddling his hair. He did not seem to mind.

It was Sid Creedy who discovered that Albert would believe almost anything he told him. They were playing football in the playground in break when Sid turned to his friends and said, ‘Watch this.’ He dribbled the ball over towards Albert, and his friends followed him.

‘My dad,’ said Sid, ‘he played centre-forward for Liverpool. Did for years. Then they asked him to play for England, but he didn’t want to – he didn’t like the colour of the shirt.’

CHAPTER TWO

THAT EVENING ALBERT TOLD HIS MOTHER all about Sid Creedy’s father, but his mother wasn’t listening, she was too busy washing up.

Encouraged by his success, Sid Creedy’s stories became more and more fantastic. ‘You know Mr Cooper, Bert?’

‘You mean the PE master?’

‘Yes, that’s him.’ Sid spoke in a confidential whisper, his arm around Albert’s shoulder. ‘Well, Bert, no one else knows this, but Mr Cooper isn’t really a teacher at all – he’s an escaped monk.’

‘How do you know that, Sid?’ said Albert.

‘You look at his head,’ said Sid. ‘It’s all bald in the middle isn’t it? You know, like Friar Tuck. Anyway I found his brown cloak in the boot of his car. He always wears sandals, and he never swears. And haven’t you noticed he sings louder than anyone else in Assembly?’

‘But why did he escape?’ said Albert.

Sid shrugged his shoulders. ‘Didn’t like the food,’ he said.

‘And he knows you know?’

‘Course he does, but I told him I’d keep it quiet. You’re the only one I’ve ever told, Bert.’

Albert went home and told his mother, but his mother was busy making his tea.

‘Mum,’ he said, ‘that Mr Cooper at school, he’s an escaped monk.’

‘Yes dear,’ she said. ‘Now get those wet shoes off before you catch your death.’

CHAPTER THREE

BACK AT SCHOOL SID CREEDY TOLD ALBERT more and more of his secrets. Every teacher at school it seemed had a deep, dark secret – even the Headmaster, Mr Manners.

Читать дальше