‘Or water first?’ Emma frowned at the TV screen and shouted: ‘Swim bladder!’

‘Bread? Crisps? This will be ready soon. Potassium chlorate!’

I felt it should be me in the onesie, with them as my helicopter parents. ‘Beer, please. Who else is coming?’

‘I asked Ros, but of course she never leaves her own postcode. The dissolution of the monasteries! She says she’d love to see you soon and lend an ear though.’

Get all the juicy details, more like, while revelling in her own two kids and semi in Hendon. I was becoming very bitter with all the solicitous, coupled-up friends who wanted to mother me. ‘Any sign of Cynth?’

‘Isiser? No, it’s not the eighties.’ Ian laughed to himself. ‘Henry the Fifth! Oh, come on, that was an easy one.’

Emma rolled her eyes. ‘Snugs, that was dreadful, even by your standards. She said she’d leave at seven. Burkina Faso!’

‘Reckon she’ll come?’ Often she didn’t leave work at all, just stayed up all night and sent out to La Perla in the morning for clean knickers. This was called ‘living the dream’, apparently.

However, I’d barely eaten my way through five hundred poppadoms when she turned up, dispensing kisses and clinking carrier bags. ‘Hello, darling.’ Immediately, I felt bad that I had brought only one bottle. But then, I was broke and she could afford to chuck away La Perla knickers, so perhaps everything was relative. I was sure there was a Bible story just like this, except without the undies—Jesus being strictly an M&S guy, I feel.

‘They let you out for good behaviour?’ In the kitchen I could see Cynthia saying hi to Ian.

‘Bad behaviour. Apparently, it’s worth more by the hour. Mmm, smells yummy. I think the last time I cooked we still thought fringes looked good.’

‘Taste.’ He held up a spoon for her to try and she closed her eyes for a second.

‘The Kelvin scale!’ shouted Emma.

‘Mmm. I can really taste the … whatever random ingredient you used that we’re supposed to be able to detect.’

‘Galangal.’

‘Yep. I can definitely taste that, whatever it is.’

‘Björn Borg!’ shouted Ian. ‘God, this lot are really thick this week.’

‘Is it nearly done, Snugs? Fermat’s Last Theorem!’ called Emma.

‘Just about. Honeybunch, don’t use those plates. They don’t match.’

‘We don’t own four that match, Snugs. You broke one last week doing air guitar to “Sweet Child O’ Mine”. The Appalachians!’

‘Oh yeah. They’ve got some on sale at Sainsbury’s. Should I pick some up?’

‘OK, and get some more cleaning wipes. We’re out. Samuel Pepys!’

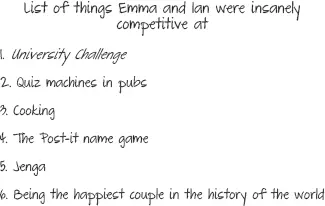

I tried not to catch Cynthia’s eye during this, partly because I still couldn’t believe this was our rebellious Emma, who’d once refused to shop in supermarkets for an entire year until they started charging for plastic bags. But also because I missed having this with someone, passing words back and forth like dishes, barely listening to what you were saying. Reminding someone to buy milk. All that.

Ian, like many men, required you to make a whole performance of admiring his food whenever he cooked. You had to look at it, smell it, guess what spices he might have used, and only then were you allowed to dig in. Dan and I had given up cooking when things got bad. We were on first-name terms with the Papa John’s delivery man—I’d even given him a Christmas card, to my shame.

‘So,’ said Emma, as soon as she’d finished wiping her plate with naan. ‘It’s Rach’s first night with us alone.’

‘Not really,’ Ian pointed out. ‘She hadn’t brought him out with her for at least the past year.’

‘He was always so busy with work,’ I said defensively. ‘I brought him. Sometimes.’

Things that suck about divorce, number thirty-four: finding out that none of your friends or family really liked your spouse in the first place; they just didn’t say so at the time when you could actually have done something about it. We’d all been at university together, so my friends had had a good ten years to get to know Dan. It was sad to think he was going to slip out of their lives too, without a backward glance.

‘It’s her first night properly alone,’ Emma repeated.

‘Do you have to keep saying “alone”?’ I was still working on my third curry helping and most likely only seconds from an Ian pun about passing out in a korma. Unlike those pale tragic women in books, misery made me eat everything in sight.

Cynthia rubbed my arm. ‘You’re not alone, darling. You’re independent and fabulous.’

Easy for her to say when she was going home to Richy Rich and their mansion with a cleaner and once-a-month gardener.

‘Anyway.’ Emma was doing her ‘could the class come to attention’ voice. ‘Rach, I know you’re feeling a bit wobbly at present.’

‘You could say that,’ I mumbled through curry. ‘Is anyone eating that?’

Ian passed over more naan. ‘Your naan,’ he said. ‘Geddit? Like your mum.’

‘Could you listen, please?’ Emma was waiting. ‘I think what you need is a project. All the books say the first few months post-split are the hardest.’

‘You read books about it?’

‘Of course. I wanted to support you.’

‘It’s a bit worrying seeing a book called Steps Through Divorce beside the bed,’ Ian said, chewing.

‘You have to be married to get divorced,’ Emma said, with a slight edge in her voice, which made me hurriedly swallow my curry.

‘So you’ve got a project for me?’

‘Better.’ She smiled triumphantly and pulled out a small notebook. ‘I’ve got a project plan .’

We all groaned. Cynthia said, ‘Not again, Em. I thought we’d talked about this scrapbooking issue.’

‘It’s nothing! Just some glue-gunning, and a bit of découpage and sketching … you know.’

‘Don’t make us do another intervention. Remember my wedding invites.’

I winced. ‘I thought we’d agreed, we do not talk about the wedding invites.’

Emma was huffing. ‘I don’t see what the fuss was about. They looked lovely. Everyone said.’

Cynthia ticked it off on her fingers. ‘They cost five hundred pounds in materials! I could have got them at the Queen’s stationer for that! They put indelible pink stains on everyone’s hands!’

‘Hand-dyed paper! It was a lovely touch.’

‘Touch was exactly what they couldn’t do.’

Ian met my eyes, pleading, as he gathered up our plates. ‘Can I see the plan?’ I said. I was the peacemaker in the group, which meant, like many peacekeepers, I was often riddled with metaphorical crossfire bullets. ‘Thank you, Em. It’s pretty.’

Emma was an excellent primary school teacher. She was authoritative, briskly kind, organised and on top of this a dab hand at cutting and gluing things. Unfortunately, she couldn’t curtail this, and so was prone to a vice you might call ‘scrapbooking gone mad’. Every page was decorated in sparkly gold pen, with glued-in photos and drawings. ‘So what’s the—’

‘Well,’ she jumped in, ‘I read in this book that the best way through a big life change is to have a list. A to-do list.’

That didn’t sound so bad. Lists were my comfort zone—I’d had interventions about this too. I turned the leaf. Page one said —do stand-up comedy . It was accompanied by a picture of me rather drunk, in a party hat, in the middle of saying something that was clearly very important. I looked up at them. ‘What is this?’

Читать дальше