“At noon,” Canceaux ’s log recorded, “the fire began to be general both in the town and vessels, but being calm the fire did not spread as wished for.” Concussion and recoil also fractured several gun carriages on the British ships—the sloop Spitfire was “much shattered,” Mowat reported—so thirty marines and sailors went ashore to toss torches through windows and doorways. The breeze picked up at two p.m., and by late afternoon Falmouth “presented a broad sheet of flame” from Parsons Lane to Fore Street.

Britain had murdered another Yankee town. The Essex Gazette tallied 416 buildings destroyed, including 136 houses, the Episcopal church, various barns, the meetinghouse, the customs house, the library, and the new courthouse. Many of the hundred structures still standing were thoroughly ventilated by balls and shells, and the three-day rain that began at ten p.m. ruined furnishings that had failed to burn. Mowat counted eleven American vessels sunk or burned, four others captured, and a distillery, wharves, and warehouses “all laid into ashes.” With his ammunition nearly spent and the flotilla badly in need of repairs, he anchored overnight in ten fathoms, then sailed for Boston. The remaining eight towns on Admiral Graves’s chastisement list would be spared.

The admiral claimed to have administered “a severe stroke to the rebels,” but he soon took a stroke himself when a letter from London arrived relieving him of command. Graves had done both too little and too much in six months of war; the Admiralty had grown weary of his excuses and the army’s complaints. He would be missed by no one except perhaps his nephews. As an act of vengeance, the razing of Falmouth may have brought brief satisfaction, but it made little sense tactically or strategically. While nearly two thousand residents sought shelter at the beginning of a Maine winter, couriers carried the news to the outside world. “It cannot be true,” the Gentleman’s Magazine opined when reports reached London. The French foreign minister called the attack “absurd as well as barbaric.” In Cambridge, General Lee denounced “the tragedy acted by these hell hounds of an execrable ministry” and recommended seizing British hostages in New York. “This is savage and barbarous,” James Warren wrote John Adams. “What more can we want to justify any step to take, kill, and destroy?”

The wolf had risen in the heart. Enraged and unified, Americans demanded revenge. Coastal towns fortified themselves and organized early warning systems with beacons and express riders. The Yale College library became an armory. Some colonial governments had already authorized privateers—merchantmen converted into warships—to attack enemy shipping, and Congress would soon follow suit. Such patriot marauders collected from a third to the entire value of a captured ship, with severe consequences in the coming years for several thousand British vessels.

Few were angrier than General Washington. He rejected Falmouth’s plea for ammunition and men—the commander in chief could hardly disperse his modest army among coastal enclaves—but in a pale fury he denounced British “cruelty and barbarity.” More clearly than ever he saw the war as a moral crusade, a death struggle between good and evil. In general orders to the troops he fulminated against “a brutal, savage enemy.” Many Americans now agreed with the sentiment published in the New-England Chronicle a month after Falmouth’s immolation: “We expect soon to break off all kinds of connections with Britain, and form into a grand republic of the American colonies.”

5.

I Shall Try to Retard the Evil Hour

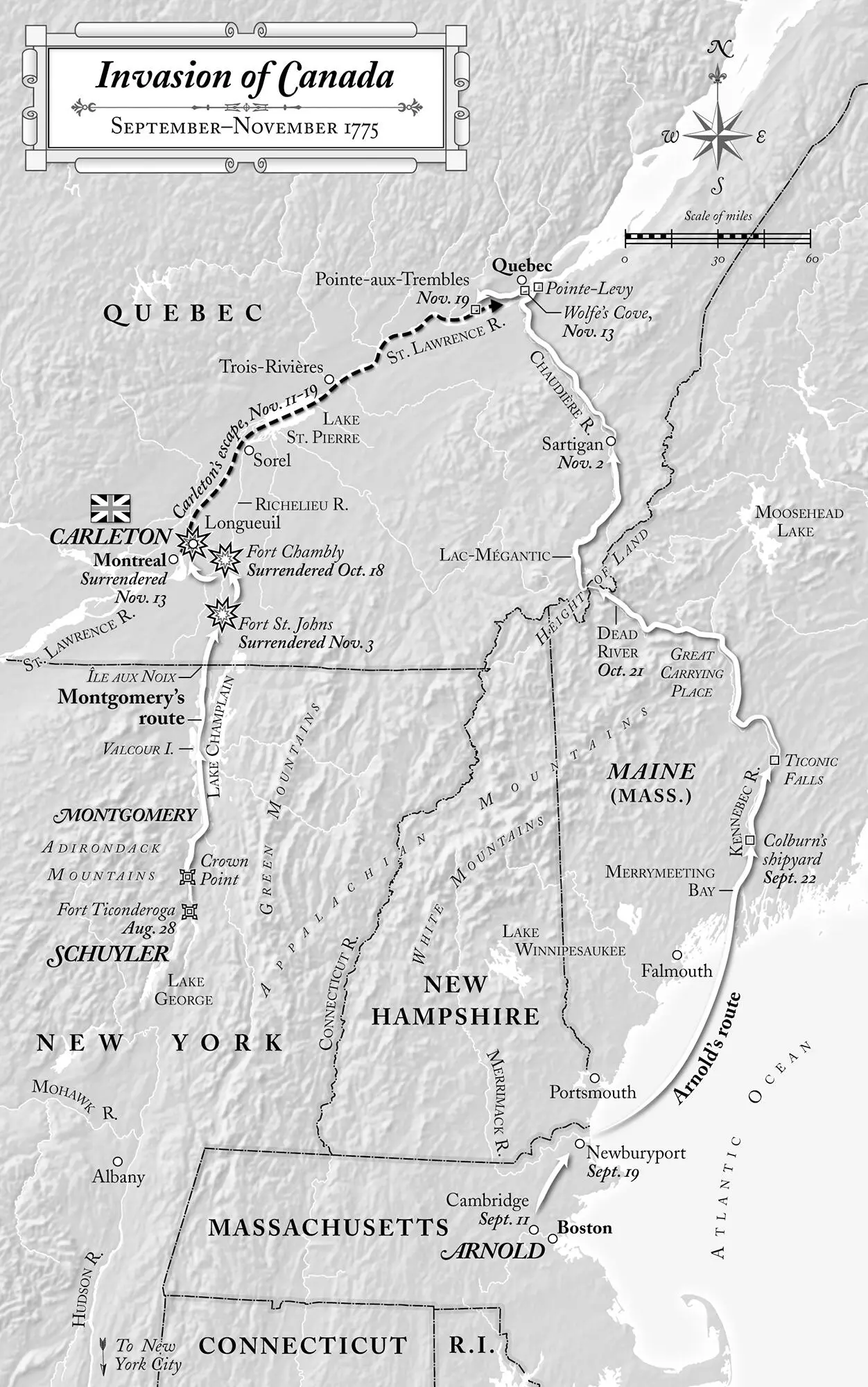

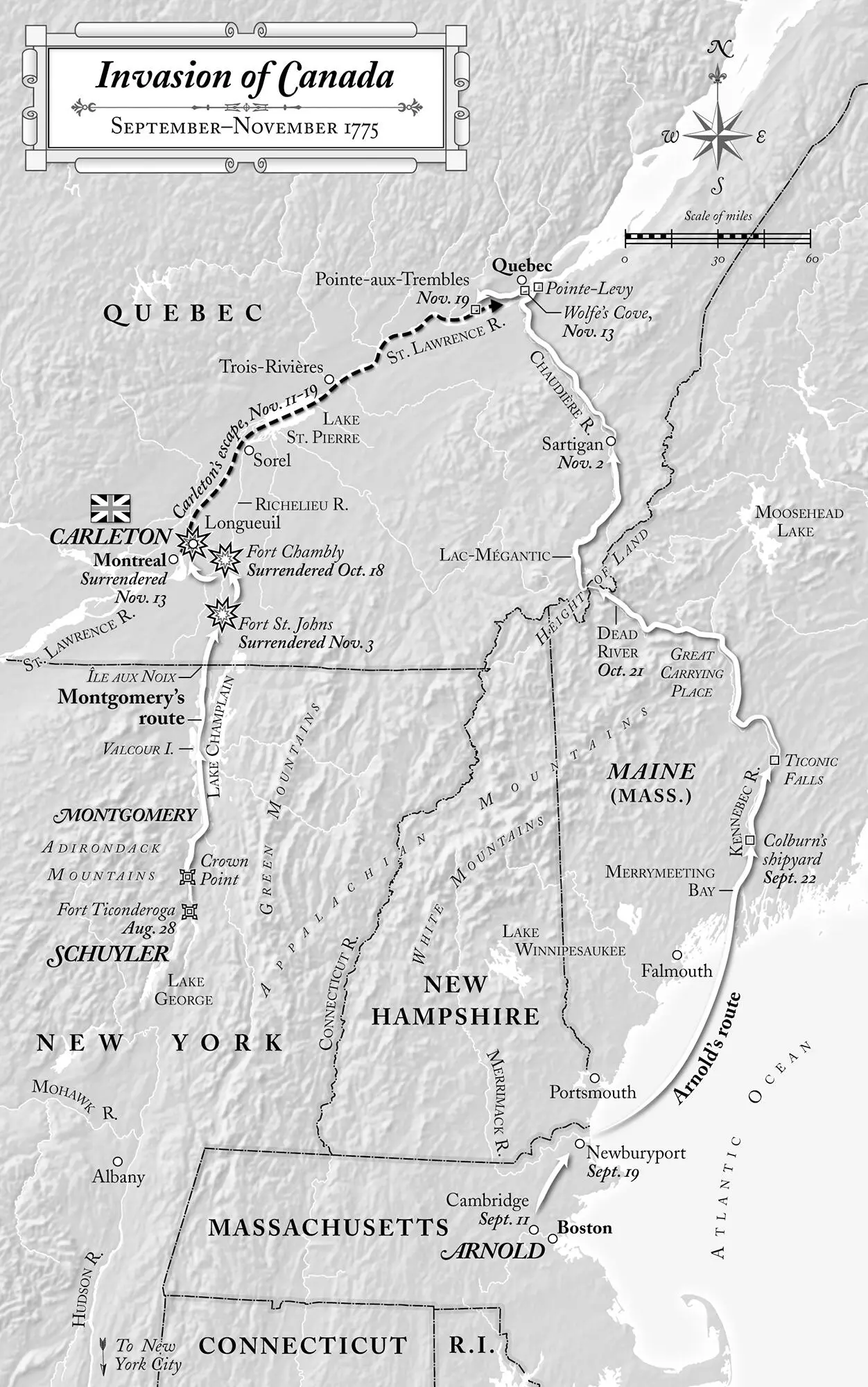

INTO CANADA, OCTOBER–NOVEMBER 1775

Some 230 miles northwest of Boston, a second siege now threatened Britain’s hold on Canada. For almost a month, more than a thousand American troops had surrounded Fort St. Johns, a dank compound twenty miles below Montreal on the swampy western bank of the Richelieu River in what one regular called “the most unhealthy spot in inhabited Canada.” A stockade and a dry moat lined with sharpened stakes enclosed a pair of earthen redoubts, two hundred yards apart and connected by a muddy trench. A small stone barracks, a bakery, a powder magazine, and several log buildings chinked with moss stood in the southern redoubt. Thirty cannons crowned the ramparts and poked through sodded embrasures, spitting iron balls whenever the rebels approached or grew too impertinent with their own artillery. By mid-October, seven hundred people were trapped at St. Johns, among them most of the British troops in Canada—drawn from the 26th Foot and the 7th Foot, known as the Royal Fusiliers—as well as most of the Royal Artillery’s gunners, eighty women and children, and more than seventy Canadian volunteers. Sentries cried, “Shot!” whenever they spotted smoke and flame from a rebel battery, and hundreds fell on their faces in the mud as the ball whizzed overhead or splatted home, somewhere.

The regulars still wore summer uniforms and suffered from the cold: the first hard frost had set on September 30, followed by eight consecutive days of rain. Some ripped the skirts from their coats to wrap around their feet. The garrison now lived on half-rations and shared a total of twenty blankets, with no bedding or straw for warmth. Only a shallow house cellar in the northern redoubt offered any shelter belowground, and it was crammed with the sick and the groaning wounded. Major Charles Preston, the fort’s dimple-chinned commandant, had sent four couriers to plead for help in Montreal. Each slipped from the fort at night and scuttled through the dense Richelieu thickets. But no reply had been heard—“not a syllable,” as Preston archly noted—since an order had arrived from the high command in early September to “defend St. Johns to the last extremity.”

At one p.m. on Saturday, October 14, many cries of “Shot!” were heard when the rebels opened a new battery with two 12-pounders and two 4-pounders barely three hundred yards away on the river’s eastern shore. One cannonball ricocheted from a chimney, demolishing the house and killing a lieutenant; another detonated a barrel of gunpowder in an orange fireball, killing another man and wounding three. Balls battered the fort’s gate and clipped its parapet. A 13-inch shell from a rebel mortar called Old Sow punched through the barracks roof, blowing out windows while killing two more and wounding five. “The hottest fire this day that hath been done here,” an officer told his diary.

The next day was just as hot: 140 rebel rounds bombarded the fort on Sunday, perforating buildings and men. A Canadian cook lost both legs. A twelve-gun British schooner, the Royal Savage , was moored between the redoubts along the western riverbank, although the crew fled to the fort after complaining that it was “impossible to sleep on board without being amphibious.” Rebel gunners now took aim at Royal Savage with heated balls, punching nine holes in the hull and three through the mainmast, then demolishing the sternpost holding the rudder. “The schooner sunk up to her ports … and her colors which lay in the hold were scorched,” a British lieutenant, John André, wrote in his journal. She soon sank with a gurgle into the Richelieu mud.

Major Preston and most of his men remained defiant, despite the paltry daily ration of roots and salt pork, despite the awful smells seeping from the cellar hospital, despite the rebel riflemen who crept close at dusk for a shot at anyone careless enough to show his silhouette on the rampart. British ammunition stocks dwindled, but gunners still sought out rebel batteries, smashing the hemlocks and the balm of Gilead trees around the American positions north and west of the fort. Yet without prompt relief—whether from Montreal, London, or heaven—few doubted that the last extremity had drawn near. “I am still alive,” wrote one of the besieged in late October, “but the will to live diminishes within me.”

Читать дальше