Gage’s adjutant complained that “every idle report is carried to headquarters and … magnified to such a degree that rebels are seen in the air carrying cannon and mortars on their shoulders.” Some regulars longed for a decisive battle; “taking the bull by the horns” became an oft-heard phrase in the regiments. “I wish the Americans may be brought to a sense of their duty,” an officer wrote in mid-June. “One good drubbing, which I long to give them … might have a good effect.” As Captain Evelyn told his cousin in London, “If there is an honor in hard knocks, we are likely to have some share.”

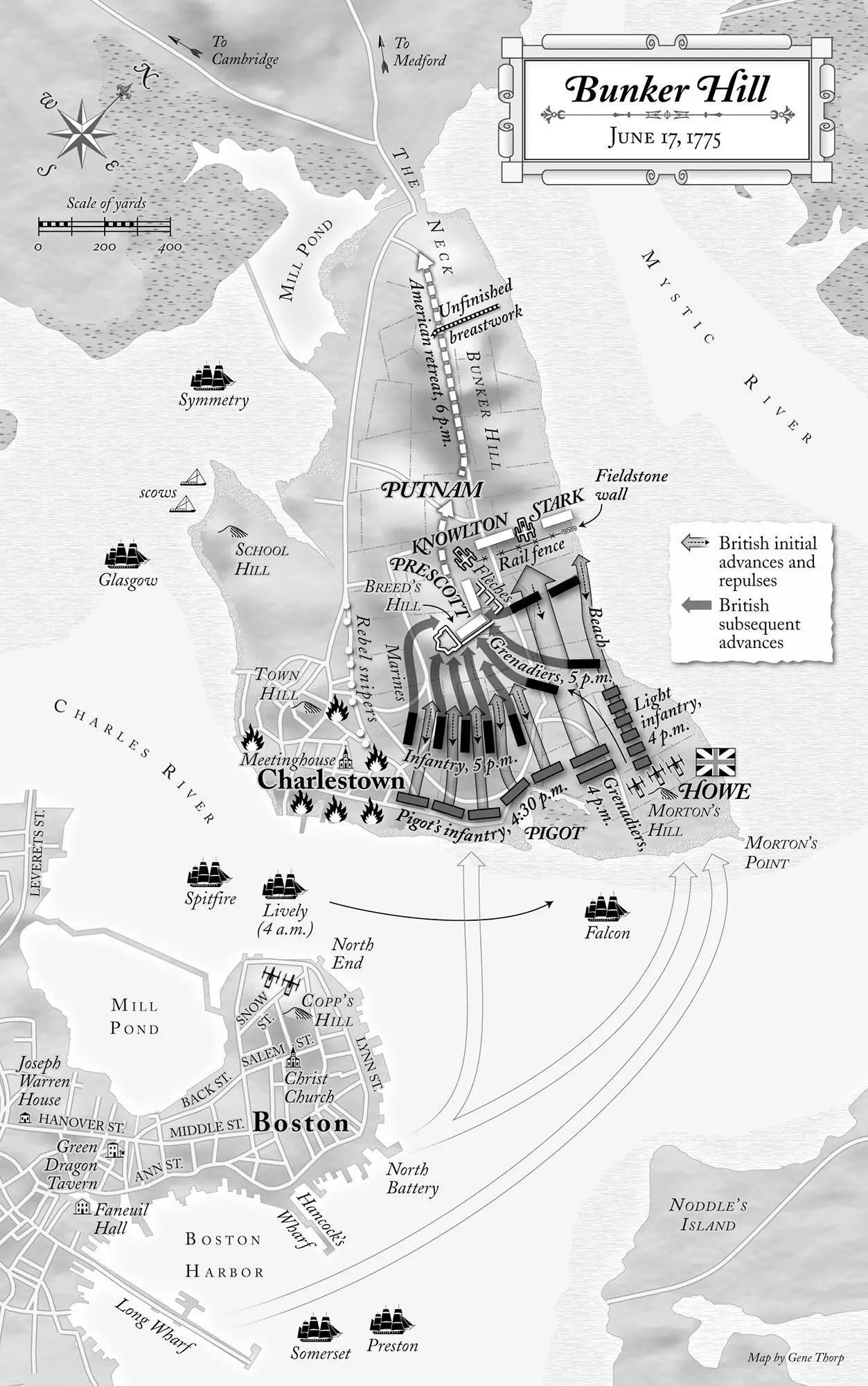

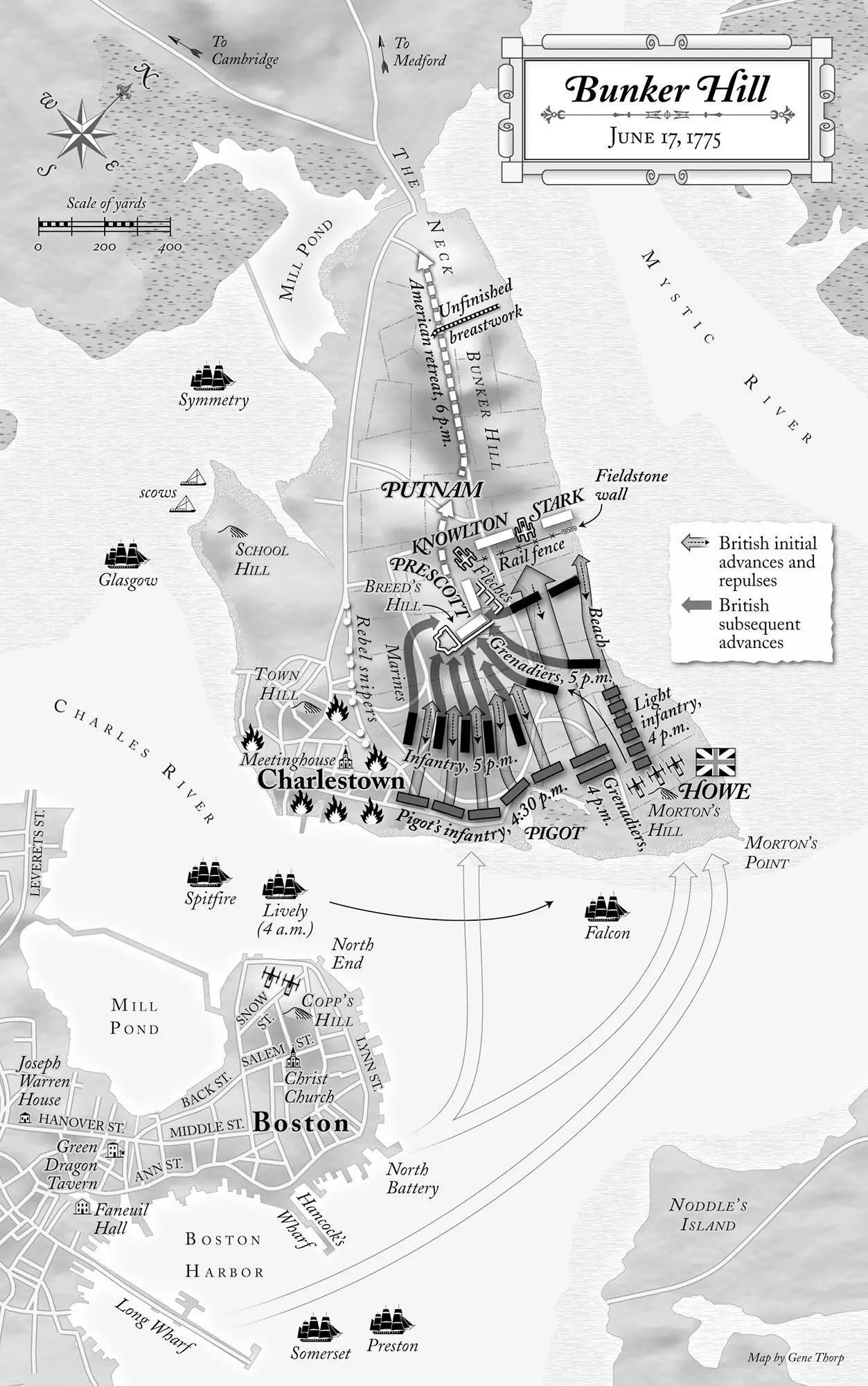

The imminent arrival of transports with light dragoons, more marines, and several foot regiments would bring the British garrison to over six thousand troops, not enough to subdue Massachusetts, much less the continent, but sufficient, as Gage told London, to “make an attempt upon some of the rebel posts, which becomes every day more necessary.” Two alluring patches of high ground remained unfortified, and Gage knew from an informant that American commanders coveted the same slopes: the elevation beyond Boston Neck known as the Dorchester Heights, and the dominant terrain above Charlestown called Bunker, or Bunker’s Hill. A battle plan was made to seize the former on Sunday, June 18, with a bombardment of Roxbury while the rebels were at church, followed by the construction of two artillery redoubts on the heights. If all went well, regulars could then capture the high ground on Charlestown peninsula and eventually attack the American encampment at Cambridge.

No sooner was the plan conceived than it leaked to the Committee of Safety; British officers seemed incapable of keeping their mouths shut in a town full of American spies and eavesdroppers. Intelligence even came from New Hampshire, where a traveler out of Boston told authorities there about rumors of an imminent British sally. Meeting in Hastings House, a gambrel-roofed mansion near the Cambridge Common, the committee on June 15 voted unanimously that “the hill called Bunker’s Hill in Charlestown be securely kept and defended.” Dorchester Heights would have to wait until more guns and powder could be stockpiled.

The American camps bustled. Arms and ammunition were inspected, with each marching soldier to carry thirty rounds. A note to the Committee of Supply advised that “the army is destitute of shirts & trousers, and if any [are] in store, pray they may be sent.” Liquor sales stopped, again. Teamsters carted the books and scientific instruments from Harvard’s library to Andover for safekeeping. Organ pipes were yanked from the Anglican church and melted down for musket bullets. An ordnance storehouse issued all forty-eight shovels in stock as well as ammunition to selected regiments—typically forty or fifty pounds of powder, a thousand balls, and a few hundred flints. Commissaries in Cambridge and Roxbury reported that provisions arriving through June 16 included 1,869 loaves of bread and 357 gallons of milk from Cambridge vendors, 60 pairs of shoes from Milton, 1,570 pounds of beef and 40 barrels of beer from Watertown, a ton of candles, 1,500 pounds of soap, several hundred barrels of beans, peas, flour, and salt fish by the quintal, rum by the hogshead, and a few hundred tents, many without poles. All Massachusetts men within twenty miles of the coast were urged to carry their firelocks “to meeting on the Sabbath and other days when they meet for public worship.” A sergeant from Wethersfield wrote his wife, “We’ve been in a great deal of hubbub.”

Orders spilled from the headquarters of Major General Ward, who occupied a southeast room on the Hastings House ground floor. Portly and sallow, sporting a powdered wig, boots, and a long coat with silver buttons, Artemas Ward, now forty-seven, had been chosen in February to command the Massachusetts militia on the strength of his long tenure in colonial politics. As a Harvard student, he once helped lead a campaign against “swearing and cursing” at the college; as a justice of the peace in Shrewsbury, he’d levied fines against the profane and could be found in the street reprimanding those who dishonored the Sabbath with unnecessary travel. Massachusetts, he believed, was home to the Chosen People. Ward had never fully recovered his health after the rigors of the French war, from which he’d emerged as a militia lieutenant colonel despite seeing little action. “Attacks of the stone”—kidney stones—still tormented him. Pious, honest, and devoted to the patriot cause, he was also taciturn, torpid, and stubborn. The gambit to hold Bunker Hill in Charlestown that he and the Committee of Safety had concocted was an impulse, not a plan. The rebel force lacked not only sufficient ammunition and field artillery but also combat reserves, a coherent chain of command, and even water. Ward had recently requested from the provincial congress almost sixty guns, fifteen hundred muskets, twenty tons of powder, and a similar quantity of lead; few of those munitions had been forthcoming.

Shortly after six p.m. on Friday, June 16, three Massachusetts regiments drifted through the arching elms and onto the Cambridge Common. They wore the usual homespun linen shirts and breeches tinted with walnut or sumac dye. Most carried a blanket or bedroll, often with a tumpline strap across the forehead to support the weight on their backs. A clergyman’s benediction droned over their bowed heads, and with a final amen they replaced their low-crowned hats and turned east down the Charlestown road.

Twilight faded and was gone, and the last birdsong faded with it. The first stars threw down their silver spears. Little rain had fallen in the past month, and dust boiled beneath each step. Candlelight gleamed from the rear of two bull’s-eye lanterns carried by sergeants at the head of the column. Officers commanded silence, and only the rattle of carts stacked with entrenching tools broke the quiet. Through parched orchards and across Willis Creek they marched, and past the hulking shadows of Prospect and Winter Hills. As they turned right toward Charlestown, a couple hundred Connecticut troops joined the column, bringing their strength to a thousand men.

General Ward had remained in his Hastings House headquarters, and the column was led by a sinewy, azure-eyed colonel wearing a blue coat with a single row of buttons and a tricorne hat. He carried a linen banyan. William Prescott of Pepperell, forty-nine and bookish, had fought twice in Canada during wars against the French, earning a reputation for cool self-possession under fire. In this war he reportedly had vowed never to be taken alive. “He was a bold man,” one soldier later wrote of him, “and gave his orders like a bold man.”

Bold orders this evening would prove to be ill-considered. As the procession crossed Charlestown Neck—barely ten yards wide at high tide—Prescott briefly conferred with the irrepressible Israel Putnam and Colonel Richard Gridley, an artilleryman and engineer who had also fought twice in Canada with distinction. From just below the isthmus, the three officers contemplated the dark contours of Charlestown peninsula, an irregular triangle a mile long and less than half that in width, bracketed by the Mystic and Charles Rivers. Even at night the dominant terrain was obvious: Bunker Hill rose gradually from the Neck for three hundred yards to a rounded crown 110 feet high, commanding not only the single land route off the peninsula, but the approach roads from Cambridge and Medford, as well as the adjacent waters. From the crest a low ridge swept southeast another six hundred yards to the patchwork of pastures, seventy-five feet high and sutured with rail fences, that would be called Breed’s Hill. Some fields had been scythed, the grass laid in windrows and cocks; in others it still stood waist-high. Brick kilns and clay pits pocked the steep eastern slope of the Breed’s pastures. Gardens and small orchards lay scattered to the west, backing the four hundred houses, shops, and buildings in Charlestown. Most of the three thousand residents had fled inland. The rising moon, three days past full, laved the town in amber light. Beyond the ferry landing and a spiny-masted warship in the Charles lay slumbering Boston.

Читать дальше