Warren circled round to that very point:

Our country is in danger, but not to be despaired of. Our enemies are numerous and powerful, but we have many friends, determining to be free.… On you depend the fortunes of America. You are to decide the important question, on which rest the happiness and liberty of millions yet unborn. Act worthy of yourselves.

Applause rocked Old South. One British lieutenant would denounce “a most seditious, inflammatory harangue,” although another concluded that the speech “contained nothing so violent as was expected.” Swords remained sheathed. But when Samuel Adams heaved himself from his chair to move that “the thanks of the town should be presented to Dr. Warren for his elegant and spirited oration,” the officers answered with more hisses, more stick rapping, and shouts of “Oh, fie! Fie!”

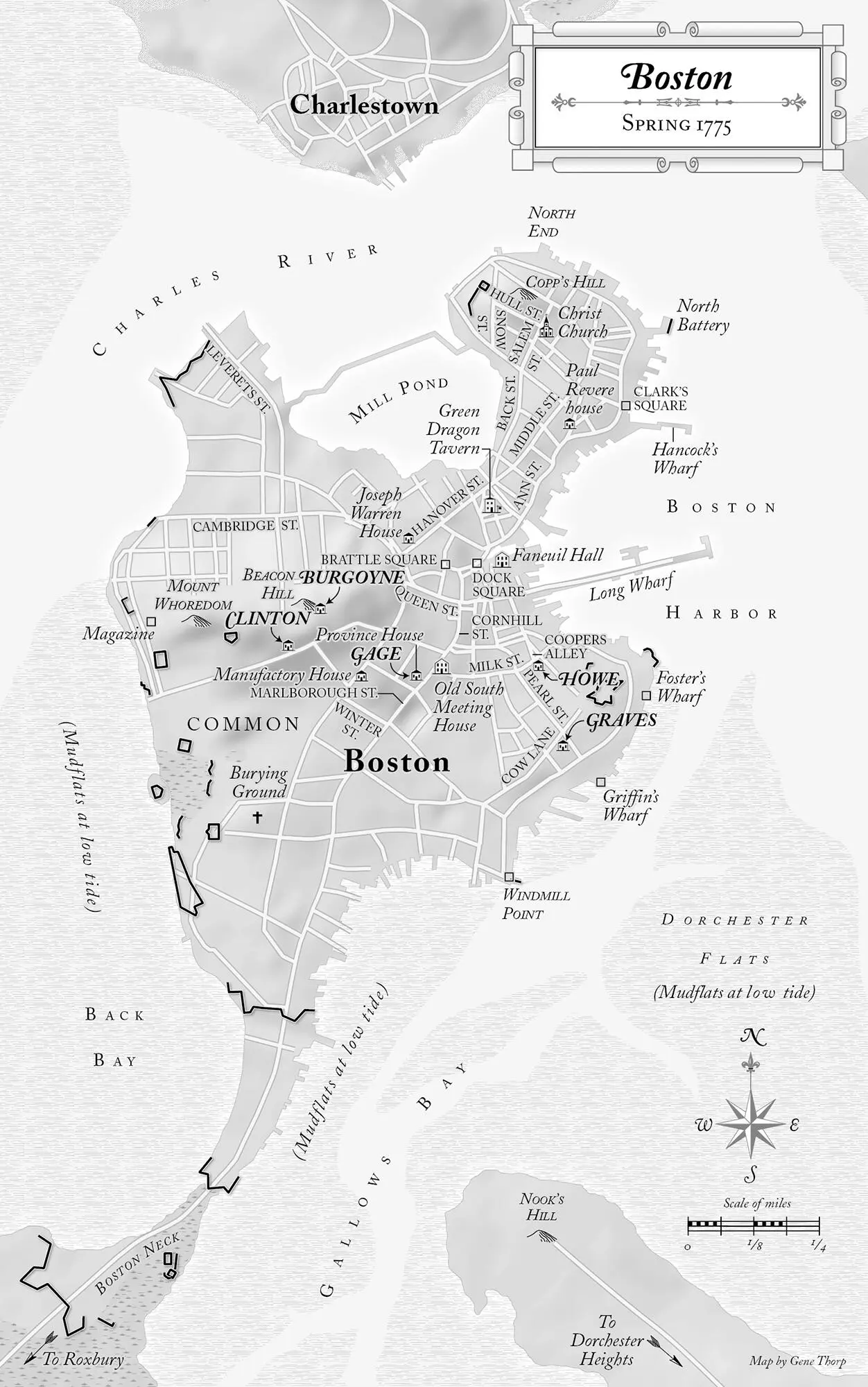

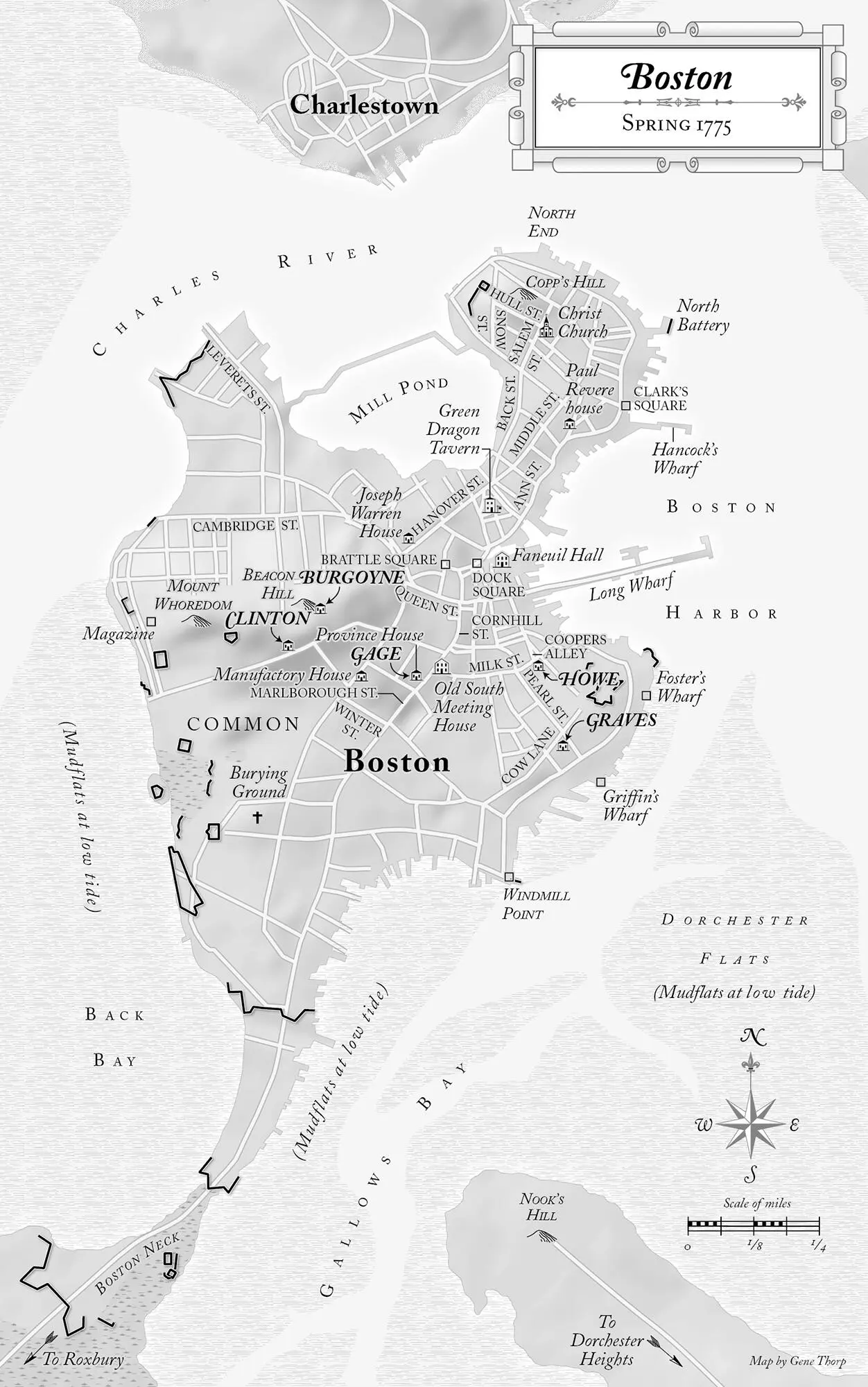

That was but a consonant removed from “fire.” Panic swept the meetinghouse, “a scene of the greatest confusion imaginable,” Lieutenant Frederick Mackenzie told his diary. Women shrieked, men shouted, “Fire!,” sniffing for smoke. Others thought a command to shoot had been issued, an error compounded by the trill and rap of fifes and drums from the 43rd Regiment, which happened to be passing in the street outside. Five thousand people tried “getting out as fast as they could by the doors and windows,” wrote Lieutenant John Barker of the 4th Regiment of Foot. The nimbler congregants in the galleries “swarmed down gutters like rats,” then hied through Coopers Alley, Cow Lane, and Queen Street.

A tense calm finally returned to a tense town. “To be sure,” Ensign Jeremy Lister of the 10th Foot later wrote, “the scene was quite laughable.”

Across the street from Old South, in the three-story brick mansion called Province House, Lieutenant General Gage was not laughing. Worried that the morning’s oration would turn violent, he had placed his regiments under arms and on alert. The risible stampede came as a relief.

Thomas Gage was a mild, sensible man with a mild, sensible countenance; only a slight protrusion of his lower lip suggested truculence. Now in his mid-fifties, with thinning gray hair and a fixed gaze, he was the most powerful authority in North America as both military commander in chief and the royal governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Comrades knew him as “Honest Tom,” and even an adversary conceded that he was “a good and wise man surrounded with difficulties.” As a young officer he had seen ghastly combat in the British defeat by the French at Fontenoy in 1745 and in the British victory over rebellious Highlanders at Culloden a year later. In 1755, he led the vanguard of General Edward Braddock’s expedition against the French in western Pennsylvania, where a disastrous ambush at the Monongahela River killed his commander and several hundred comrades; swarming bullets grazed Gage’s belly and eyebrow, ventilated his coat, and twice wounded his horse. Three years later, Gage was a senior commander when the French battered a British expedition in New York at Fort Carillon, subsequently renamed Ticonderoga. These actions revealed a soldier without conspicuous gifts as a combat leader, a man perhaps meant to administer rather than command. It was Gage’s misfortune to live in turbulent times.

Even so, twenty years of American service had been good to him, providing Gage with high rank, a comely American wife—the New Jersey heiress Margaret Kemble—and vast tracts of land in New York, Canada, and the West Indies. He evinced little sympathy for American political experiments. “Democracy is too prevalent in America,” he had declared in 1772, when his headquarters was in New York.

The tea party had pushed his lower lip out a bit more. In an uncharacteristic fit of bravado during a return visit to London in February 1774, he assured King George that four regiments in Boston should suffice—perhaps two thousand men—since the Americans would be “lions whilst we are lambs” but would turn “very meek” in the face of British resolve. Other colonies were unlikely to support Massachusetts; southerners especially “talk very high,” but the fear of slave rebellions and Indian attacks “will always keep them quiet.” The thirteen colonies seemed too geographically scattered and too riven by diverse interests to collaborate effectively. Promises of suppression on the cheap appealed to the shilling pinchers in Lord North’s government. Gage’s views had also helped shape the Coercive Acts by feeding the pleasant delusion in Britain that insurrection was mostly a Boston phenomenon, organized by a small cabal of ambitious cynics able to gull the masses.

Gage’s report so encouraged the king and his court that the general was dispatched to Massachusetts as both governor of the colony and military chief of the continent. Respectful Bostonians had greeted him with an honor guard, banners, and toasts in Faneuil Hall, although two weeks later he shifted his headquarters to Salem, upon closing Boston Harbor at noon on June 1, 1774. His marching orders from the government urged him “to quiet the minds of the people, to remove their prejudices, and, by mild and gentle persuasion to induce … submission on their part.” He imposed neither martial law nor press censorship. Troublemakers were permitted to assemble, to travel, to drill their militias, to fling bellicose insults at the king’s regulars.

Gage had evidently learned little on the Monongahela or at Fort Carillon about the hazard of underestimating his adversaries; precisely what he had absorbed from two decades in America was unclear. But within weeks of planting his flag in Salem, he recognized that he had misjudged both the depth and the breadth of rebellion. The Coercive Acts, including the abrogation of colonial government in Massachusetts, had inflamed the insurrection. One ugly incident followed another. In mid-August, fifteen hundred insurgents prevented royal judges and magistrates from taking the bench in Berkshire County in western Massachusetts. Two weeks later, Gage sent foot troops to seize munitions from the provincial powder house, six miles northwest of Boston; rumors spread that the king’s soldiers and sailors were butchering Bostonians. At least twenty thousand rebels marched toward the town with firelocks, cudgels, and plowshares beaten into edged weapons. “For about fifty miles each way round, there was an almost universal ferment, rising, seizing arms,” wrote one clergyman. An Irish merchant described how “at every house women & children [were] making cartridges” and pouring molten lead into bullet molds. The insurgents found Boston unbruised and the British regulars back in their fortified camps, but the “Powder Alarm” emboldened the Americans, demonstrated the militancy of bumpkins in farms and villages across the colony, and revealed how crippled the Crown’s authority had become. “Popular rage has appeared,” Gage advised London.

Additional episodes followed. More than four thousand militiamen lined the main street in Worcester in early September, closing the royal courts and requiring two dozen officials to walk a quarter-mile gantlet, hats in hand, each recanting his loyalty to the Crown thirty times, aloud. A Massachusetts Provincial Congress convened in Salem in early October 1774 to elect the wealthy merchant John Hancock as president—a vain, petulant “empty barrel,” in John Adams’s estimation. Of more than two hundred Massachusetts communities, only twenty-one failed to send delegates. Like similar congresses soon established in other colonies, this extralegal assembly acted as a provisional government to circumvent British authority by passing resolutions, collecting revenue, and coordinating colonial affairs with the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Читать дальше