The only fossilized remains of actual dinosaurs in Australia are of occasional scattered bones and teeth; yet there is now a growing understanding of the variety of the dinosaur population derived from the fossilized trackways set in stone. They are usually left undisturbed for visitors to enjoy, though this inevitably exposes them to damage. Trackways left by theropod dinosaurs were discovered at the eastern side of Australia when palæontologists first discovered the footprints of a theropod dinosaur in tidal strata at Flat Rocks, Victoria, in 2006. Thousands of scattered bones and teeth have been found in the area, and the dinosaur footprints – measuring about 1 foot (30 cm) across – were left intact for visitors; however, there was no sign pointing them out. In December 2017 someone took a hammer and chisel and chopped out the toes, leaving them scattered nearby. The local Park Ranger, Brian Martin, said: ‘They would need to know exactly where it is to find it. Most people quite easily walk right past it,’ he said. This time the vandals didn’t.

We are beginning to understand how huge some of these monsters were. The massive brachiosaurs which appear so frequently in documentaries and pictures about dinosaurs were colossal creatures measuring about 85 feet (26 metres) long and weighing at least 50 tons, their footprints measuring less than 3 feet (90 cm) in length. Similarly, some unprecedently gigantic footprints were discovered in Mongolia in 2016, each measuring 3 feet 6 inches (1.06 metres) long, which caused considerable surprise among palæontologists. There are Australian huge dinosaur footprints that measure 5 feet 7 inches (1.7 metres) from heel to toe. Nothing so vast has ever been discovered elsewhere.16

Fossilized shells had been known for centuries and, as we have seen, they were conventionally interpreted as a natural consequence of the biblical flood. They were written about as radical new thinkers appeared on the European scene, and they caught the attention of Leonardo da Vinci around 1508, two centuries before the Enlightenment. Leonardo was not inclined to believe that they were the aftermath of the biblical accounts of the Noahic flood. Instead, he thought that their presence showed that the surface of the Earth had changed over time, and the fossilized remains represented an earlier, watery phase of the Earth’s ancient history. A generation later, a French Huguenot hydraulics engineer and ceramicist named Bernard Palissy wrote on the origins of fossils. He too believed that they were not the result of a flood, but had formed naturally in a manner reminiscent of that recorded by Avicenna. Palissy thought that mineral-rich water developed ‘congelative properties’ that transformed once-living creatures to stone. The first report of fossilized bones in Europe dates from 1605, when a British expatriate theologian named Richard Verstegan (living in Antwerp) became interested in fossils and, for the first time, recognized bones and teeth for what they were.17

Verstegan portrayed ichthyosaur vertebræ in a book, though he interpreted them as the remains of fish, which he took as evidence that Britain and mainland Europe were once connected.18

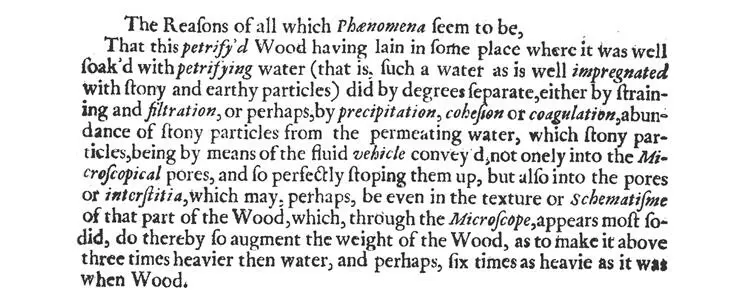

Fossils were collected by many enthusiasts during this period, though the first time they were scientifically described was by Robert Hooke in 1665. Hooke was a remarkable polymath and is best known for his role as the founding father of the science of the microscope. In his large folio volume Micrographia , published in 1665, Hooke devoted a section to fossils. His microscope showed him that fossilized wood had a structure identical to that of wood taken from a tree nearby, and he described the fossil in terms that fit perfectly with our modern understanding.

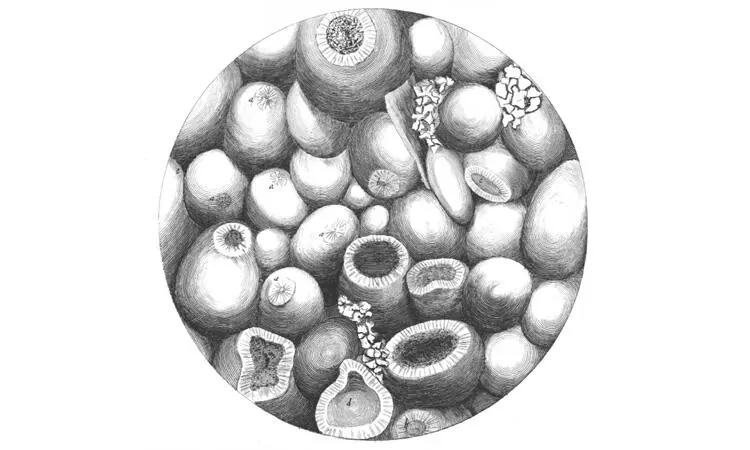

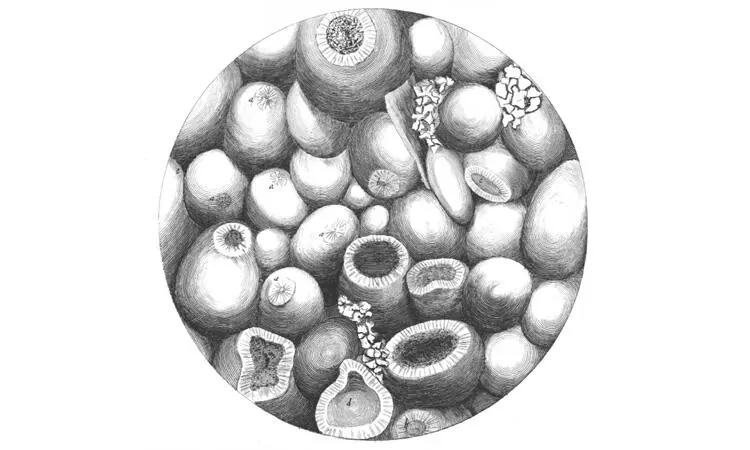

Hooke also featured a fine image of the microscopic spheres that comprise limestone. His drawing, captioned ‘Kettering-stone’, was described in his text: ‘This stone is brought from Kettering in Northampton-shire, and digg’d out of a Quarry, as I am inform’d.’19

His specimen was demonstrated to the Fellows of the Royal Society on Sunday, April 15, 1663, and attracted much attention. That was an auspicious date; his other demonstration that day was of thin sections of cork. Hooke observed that the specimen (from a wine bottle) showed itself to comprise numerous small boxes, the cell walls of the cork. The room-like nature of each component led Hooke to call them ‘cells’ – and this is the term that has come down to us today for all the cells that we see in living organisms.20

British philosopher Robert Hooke announced the first reasoned account of the process of fossilization in his book Micrographia , published in 1665. He thought that organic remains became filled with ‘stony particles’ and thus became petrified.

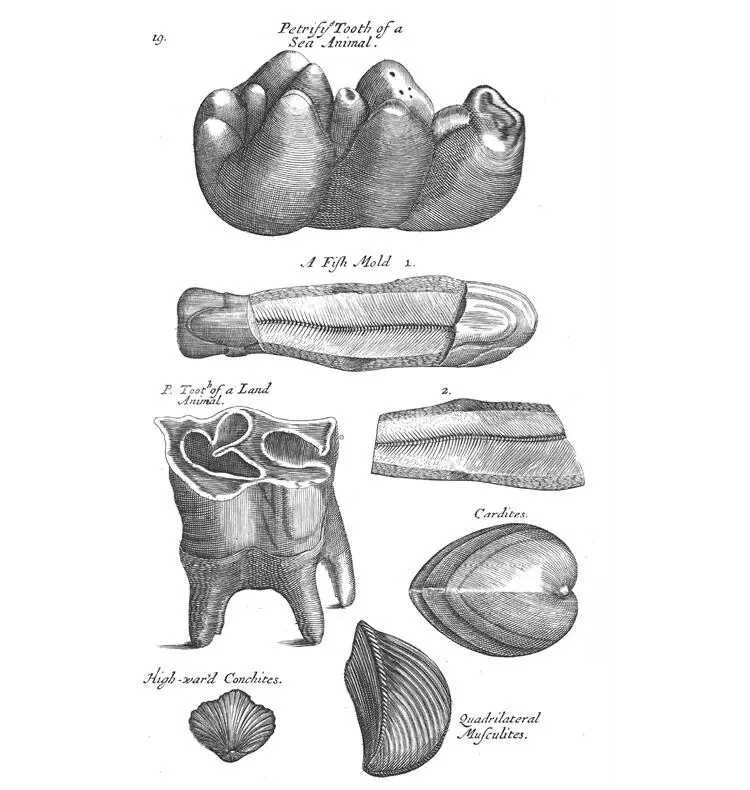

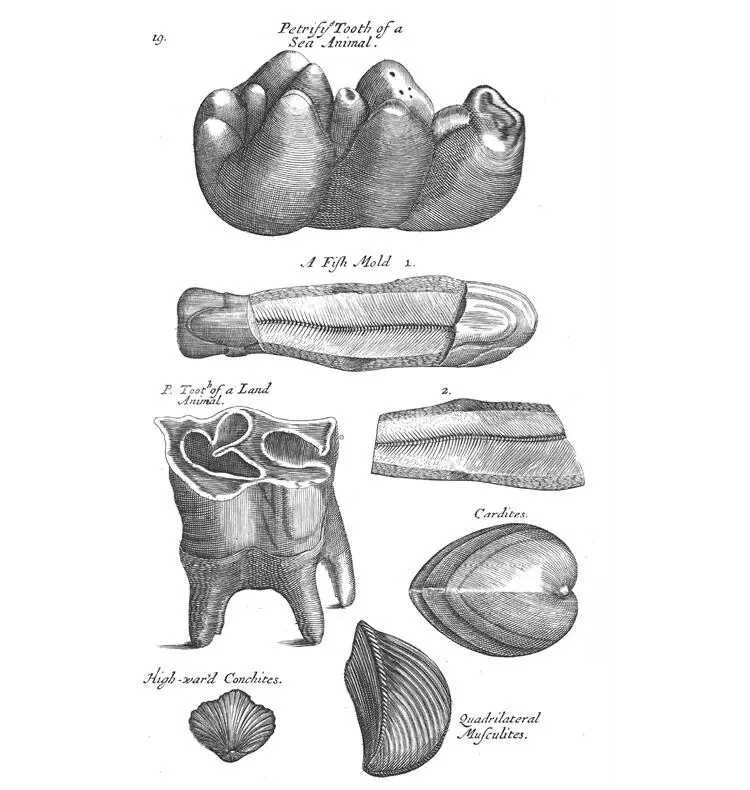

There were other fossils in the Royal Society collections at the time, and examples ranging from fossilized teeth to skeletons of fish were included in the Society’s catalogue of rarities, with descriptions showing that the petrification of organic remains was understood as a natural process.21

Under his microscope, Hooke could study the fractured surface of this Middle Jurassic oolite rock. He was the first to make detailed studies of rock formations and his conclusions about the processes of fossilization proved to be influential.

The collecting of fossils soon became a popular hobby for the learned classes. In 1695 John Woodward was appointed the first Professor of Geology at Cambridge University. He recognized the widespread occurrence of fossils and taught that they had been laid down by floods to form successive strata. Woodward became an avid collector of fossils and minerals, and eventually amassed over 9,000 specimens. He donated them all to the University, where they became the nucleus of what later became the Sedgwick Museum. In 1699 Edward Lhuyd published accurate engravings of ichthyosaur bones, vertebræ and limb elements in a book along with fossilized shark’s teeth and sea urchins, and a variety of petrified seashells and ferns.22

Lhuyd was appointed assistant to Robert Plot, a graduate of Magdalen Hall, Oxford, who had been appointed Professor of Chemistry and the first Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in March 1683. It was Plot who published the first book to feature a picture of a dinosaur bone, The Natural History of Oxfordshire ,23 in June 1677. He did not know what it was, and believed it to be a fossilized thigh-bone from a biblical giant, though it looked like a fossilized scrotum. Lhuyd went on to succeed Plot as Keeper.

Nehemiah Grew published pictures including ‘Animal Bodies Petrify’d’ as table 19 in the book Musæum Regalis Societatis , or, A catalogue and description of the Natural and Artificial Rarities … , which the Royal Society published in 1681.

By the end of the seventeenth century, popular fossil finds were becoming more familiar in Britain and many had been well documented. In Switzerland, as in England, fossilized bones were always assumed to be human, and so when naturalist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer described two ichthyosaur vertebræ in 1708 he identified them as being the mortal remains of a person who had been drowned in the biblical flood and named them Homo diluvia tristis testi (‘sad evidence of man in the floods’).

Читать дальше