Practice theorists are interested in questions of social reproduction and social transformation – why, in other words, things sometimes change and sometimes remain the same. One concept practice theorists have used to explain this process is Bourdieu’s notion of habitus , which he uses to refer to a set of predispositions that produce practices and representations conditioned by the structures from which they emerge. These practices and their outcomes then reproduce or transform the habitus – whether people intend them to do so or not (Bourdieu 1977:78). Habitus can be a very illuminating concept, for it can be used to describe how people socialized in a certain way will often share many perspectives and values, as well as styles of eating, talking, or behaving. To simplify, habitus refers to how we are predisposed (though not required) to think and act in certain ways because of how we have been socialized. And usually, once we act upon these predispositions, we end up reproducing the very conditions and social structures that shaped our thoughts and actions to start with. Not always, however. Because of the tensions and contradictions inherent in the habitus , actors are neither free agents nor completely socially determined products. Instead, Ortner (1989:198) suggests that they are “loosely structured.” The central question for practice theorists, then, is determining how such loosely structured actors manage at times to transform the systems that produce them.

Such loose structuring can occur linguistically as well as socioculturally. Many linguistic anthropologists therefore find it useful to draw upon practice theory explicitly or implicitly in their work. Speakers of a given language are constrained to some degree by the grammatical structures of their particular language, but they are still capable of producing an infinite number of grammatically well-formed utterances within those constraints. Moreover, languages, like cultures, change over time through drift and contact despite their supposedly self-reproducing structures. It is therefore helpful to look closely at language (both its grammatical structures and its patterns of use) in order to gain a more thorough understanding of how people reproduce and transform both language and culture.

Social systems – languages, habitus , structures, cultures, etc. – are created and recreated, reinforced, reshaped, and reconfigured by the actions and words of particular individuals, groups, and institutions acting in socioculturally conditioned ways. In other words, languages and cultures emerge dialogically in a continuous manner through the social and linguistic interactions of individuals “always already situated in a social, political, and historical moment” (Mannheim and Tedlock 1995:9). Neither structure nor practice, therefore, should be seen as analytically prior to the other. Instead, each should be seen as being embedded in the other. Social and linguistic structures emerge from the everyday actions of real people, and vice versa.

The concept of emergence as it is used here originated in biology, and it goes beyond the simple everyday sense in which one thing gives rise to another. In addition to this sense, emergence as it is used in linguistic anthropology (as well as other fields) also refers to instances when the whole is more than the sum of the parts. Ernst Mayr, the famous biologist, writes of inorganic as well as organic systems that they “almost always have the peculiarity that the characteristics of the whole cannot (not even in theory) be deduced from the most complete knowledge of the components, taken separately or in other partial combinations. This appearance of new characteristics in wholes has been designated as emergence ” (1982:63, emphasis in the original). Mayr is quick to point out that there is nothing mystical about such a view of emergence; in fact, the characteristics (for example, its liquidity) of a system as “simple” as water cannot, according to Mayr, be deduced from a study of its hydrogen and oxygen atoms. Language, as a whole, cannot be understood merely from a study of its grammatical features. Likewise, language, culture, and social structures emerge from social practice on the part of individuals but cannot be understood with reference only to those individuals.

Nevertheless, emergence does not imply absolute, unconstrained unpredictability. On the contrary, Mannheim and Tedlock (1995:18) emphasize that cultures have their own organizing principles that emerge through the linguistic and social interactions of individuals who themselves embody and enact social structures and cultural patterns, just as practice theorists maintain. Take, for example, the actions of individuals who are protesting something in their society by engaging in street demonstrations. Their underlying assumptions, methods, and principles are very likely to have been deeply influenced by the very norms that they are protesting, even if the individuals work extremely hard to counter such influences. What emerges from such formal protests, as well as from informal, everyday activities, is shaped and constrained by these influences – but not totally determined. Understanding the constrained yet at least partially indeterminate outcomes of human actions can help explain how social and linguistic structures that usually reproduce themselves nevertheless always change over time. Whether reproduction or transformation results, all languages and cultures can be said to be emergent from social and linguistic practice.

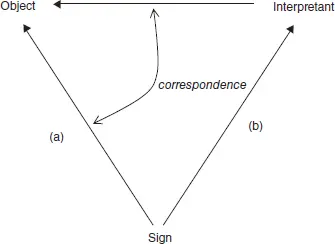

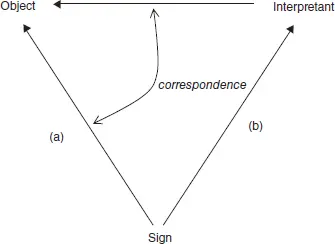

Identifying the precise ways in which language and social relations intersect is one of the most pressing issues in linguistic anthropology. A key concept that assists scholars in pinpointing these intersections is “indexicality” (Hanks 1999), which, as it is used here, stems from Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotics (Peirce 1955; cf. Mertz 2007b). Semiotics, the study of signs, can seem somewhat complex but it is well worth going over some of the essentials in order to obtain a fuller understanding of the term “indexicality.” Semiotics starts with the definition of the linguistic sign. Perhaps the best-known definition is de Saussure’s: a sign is the link between a concept (the “signified”) and a sound pattern (the “signifier”) (Saussure 1986:66). Thus, in de Saussure’s famous example, the word “tree” is a sign because it links the mental concept of a tree with the pattern of sounds that comprises the word. For Peirce, however, semiosis, or meaning-making through signs, involves a concept of the linguistic sign that is quite different from de Saussure’s, for it is a process that “involves three components: signs (whatever stands for something else), objects (whatever a sign stands for), and interpretants (whatever a sign creates insofar as it stands for an object)” (Kockelman 2007:376; see Figure 1.6). In other words, meaning-making involves a sign such as the word “tree,” the object that is represented, such as the actual tree – so far, these two aspects could be said to be fairly similar to de Saussure’s “signifier” and “signified” – but then there is in Peirce’s model the extremely important interpretant – the effect or outcome of the semiotic relationship between the sign and the object , such as a feeling of appreciation for the beauty of a tree. Peirce’s tripartite signs do not reside solely in one person’s head, therefore, as de Saussure’s signs do, but extend out into the physical and social world.

Figure 1.6Semiosis as a relation between relations.

Читать дальше