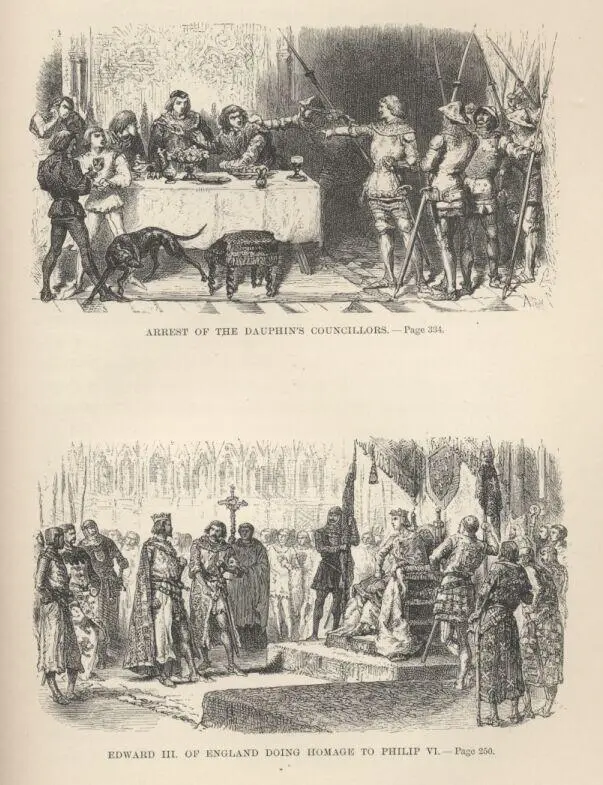

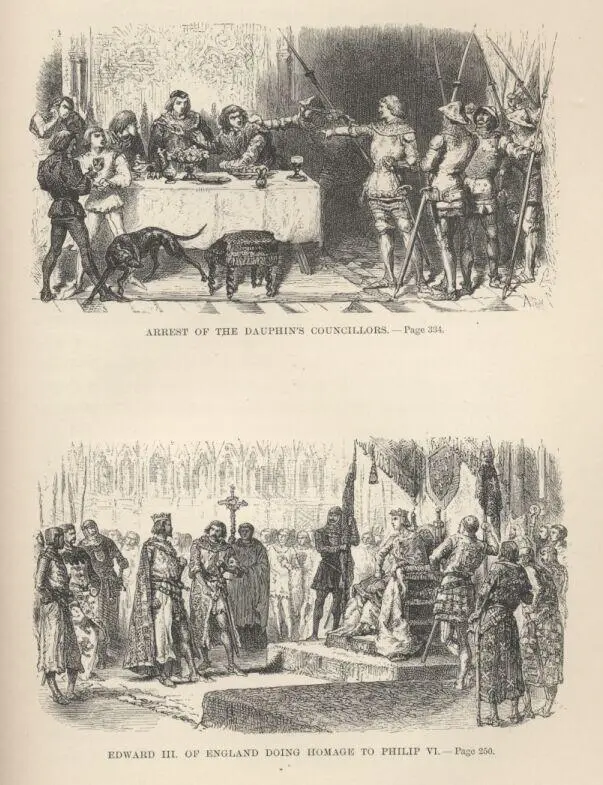

As we have seen in the preceding chapter, the elevation of Philip of Valois to the throne, as representative of the male line amongst the descendants of Hugh Capet, took place by virtue, not of any old written law, but of a traditional right, recognized and confirmed by two recent resolutions taken at the death of the two eldest sons of Philip the Handsome. The right thus promulgated became at once a fact accepted by the whole of France; Philip of Valois had for rival none but a foreign prince, and “there was no mind in France,” say contemporary chroniclers, “to be subjects of the King of England.” Some weeks after his accession, on the 29th of May, 1328, Philip was crowned at Rheims, in presence of a brilliant assemblage of princes and lords, French and foreign; and next year, on the 6th of June, Edward III., King of England, being summoned to fulfil a vassal’s duties by doing homage to the King of France for the duchy of Aquitaine, which he held, appeared in the cathedral of Amiens, with his crown on his head, his sword at his side, and his gilded spurs on his heels. When he drew near to the throne, the Viscount de Melun, king’s chamberlain, invited him to lay aside his crown, his sword, and his spurs, and go down on his knees before Philip. Not without a murmur, Edward obeyed; but when the chamberlain said to him, “Sir, you, as Duke of Aquitaine, became liegeman of my lord the king who is here, and do promise to keep towards him faith and loyalty,” Edward protested, saying that he owed only simple homage, and not liege-homage—a closer bond, imposing on the vassal more stringent obligations [to serve and defend his suzerain against every enemy whatsoever]. “Cousin,” said Philip to him, “we would not deceive you, and what you have now done contenteth us well until you have returned to your own country, and seen from the acts of your predecessors what you ought to do.”

“Gramercy, dear sir,” answered the King of England; and with the reservation he had just made, and which was added to the formula of homage, he placed his hands between the hands of the King of France, who kissed him on the mouth, and accepted his homage, confiding in Edward’s promise to certify himself by reference to the archives of England of the extent to which his ancestors had been bound. The certification took place, and on the 30th of March, 1331, about two years after his visit to Amiens, Edward III. recognized, by letters express, “that the said homage which we did at Amiens to the King of France in general terms, is and must be understood as liege; and that we are bound, as Duke of Aquitaine and peer of France, to show him faith and loyalty.”

The relations between the two kings were not destined to be for long so courteous and so pacific. Even before the question of the succession to the throne of France arose between them they had adopted contrary policies. When Philip was crowned at Rheims, Louis de Nevers, Count of Flanders, repaired thither with a following of eighty-six knights, and he it was to whom the right belonged of carrying the sword of the kingdom. The heralds-at-arms repeated three times, “Count of Flanders, if you are here, come and do your duty.” He made no answer. The king was astounded, and bade him explain himself. “My lord,” answered the count, “may it please you not to be astounded; they called the Count of Flanders, and not Louis de Nevers.” “What then!” replied the king; “are you not the Count of Flanders?” “It is true, sir,” rejoined the other, “that I bear the name, but I do not possess the authority; the burghers of Bruges, Ypres, and Cassel have driven me from my land, and there scarce remains but the town of Ghent where I dare show myself.” “Fair cousin,” said Philip, “we will swear to you by the holy oil which hath this day trickled over our brow that we will not enter Paris again before seeing you reinstated in peaceable possession of the countship of Flanders.” Some of the French barons who happened to be present represented to the king that the Flemish burghers were powerful; that autumn was a bad season for a war in their country; and that Louis the Quarreller, in 1315, had been obliged to come to a stand-still in a similar expedition. Philip consulted his constable, Walter de Chatillon, who had served the kings his predecessors in their wars against Flanders. “Whoso hath good stomach for fight,” answered the constable, “findeth all times seasonable.” “Well, then,” said the king, embracing him, “whoso loveth me will follow me.” The war thus resolved upon was forthwith begun. Philip, on arriving with his army before Cassel, found the place defended by sixteen thousand Flemings under the command of Nicholas Zannequin, the richest of the burghers of Furnes, and already renowned for his zeal in the insurrection against the count. For several days the French remained inactive around the mountain on which Cassel is built, and which the knights, mounted on iron-clad horses, were unable to scale. The Flemings had planted on a tower of Cassel a flag carrying a cock, with this inscription:—

| “When the cock that is hereon shall crow, The foundling king herein shall go.” |

They called Philip the foundling king because he had no business to expect to be king. Philip in his wrath gave up to fire and pillage the outskirts of the place. The Flemings marshalled at the top of the mountain made no movement. On the 24th of August, 1328, about three in the afternoon, the French knights had disarmed. Some were playing at chess; others “strolled from tent to tent in their fine robes, in search of amusement;” and the king was asleep in his tent after a long carouse, when all on a sudden his confessor, a Dominican friar, shouted out that the Flemings were attacking the camp. Zannequin, indeed, “came out full softly and without a bit of noise,” says Froissart, “with his troops in three divisions, to surprise the French camp at three points. He was quite close to the king’s tent, and some chroniclers say that he was already lifting his mace over the head of Philip, who had armed in hot haste, and was defended only by a few knights, of whom one was waving the oriflamme round him, when others hurried up, and Zannequin was forced to stay his hand. At two other points of the camp the attack had failed. The French gathered about the king and the Flemings about Zannequin; and there took place so stubborn a fight, that “of sixteen thousand Flemings who were there not one recoiled,” says Froissart, “and all were left there dead and slain in three heaps one upon another, without budging from the spot where the battle had begun.” The same evening Philip entered Cassel, which he set on fire, and, in a few days afterwards, on leaving for France, he said to Count Louis, before the French barons, Count, I have worked for you at my own and my barons’ expense; I give you back your land, recovered and in peace; so take care that justice be kept up in it, and that I have not, through your fault, to return; for if I do, it will be to my own profit and to your hurt.”

The Count of Flanders was far from following the advice of the King of France, and the King of France was far from foreseeing whither he would be led by the road upon which he had just set foot. It has already been pointed out to what a position of wealth, population, and power, industrial and commercial activity had in the thirteenth century raised the towns of Flanders, Bruges, Ghent, Lille, Ypres, Fumes, Courtrai, and Douai, and with what energy they had defended against their lords their prosperity and their liberties. It was the struggle, sometimes sullen, sometimes violent, of feudal lordship against municipal burgherdom. The able and imperious Philip the Handsome had tested the strength of the Flemish cities, and had not cared to push them to extremity. When, in 1322, Count Louis de Nevers, scarcely eighteen years of age, inherited from his grandfather Robert III. the countship of Flanders, he gave himself up, in respect of the majority of towns in the countship, to the same course of oppression and injustice as had been familiar to his predecessors; the burghers resisted him with the same, often ruffianly, energy; and when, after a six years’ struggle amongst Flemings, the Count of Flanders, who had been conquered by the burghers, owed his return as master of his countship to the King of the French, he troubled himself about nothing but avenging himself and enjoying his victory at the expense of the vanquished. He chastised, despoiled, proscribed, and inflicted atrocious punishments; and, not content with striking at individuals, he attacked the cities themselves. Nearly all of them, save Ghent, which had been favorable to the count, saw their privileges annulled or curtailed of their most essential guarantees. The burghers of Bruges were obliged to meet the count half way to his castle of Vale, and on their knees implore his pity. At Ypres the bell in the tower was broken up. Philip of Valois made himself a partner in these severities; he ordered the fortifications of Bruges, Ypres, and Courtrai to be destroyed, and he charged French agents to see to their demolition. Absolute power is often led into mistakes by its insolence; but when it is in the hands of rash and reckless mediocrity, there is no knowing how clumsy and blind it can be. Neither the King of France nor the Count of Flanders seemed to remember that the Flemish communes had at their door a natural and powerful ally who could not do without them any more than they could do without him. Woollen stuffs, cloths, carpets, warm coverings of every sort were the chief articles of the manufactures and commerce of Flanders; there chiefly was to be found all that the active and enterprising merchants of the time exported to Sweden, Norway, Hungary, Russia, and even Asia; and it was from England that they chiefly imported their wool, the primary staple of their handiwork. “All Flanders,” says Froissart, “was based upon cloth and no wool, no cloth.” On the other hand it was to Flanders that England, her land-owners and farmers, sold the fleeces of their flocks; and the two countries were thus united by the bond of their mutual prosperity. The Count of Flanders forgot or defied this fact so far as in 1336, at the instigation, it is said, of the King of France, to have all the English in Flanders arrested and kept in prison. Reprisals were not long deferred. On the 5th of October in the same year the King of England ordered the arrest of all Flemish merchants in his kingdom and the seizure of their goods; and he at the same time prohibited the exportation of wool. “Flanders was given over,” says her principal historian, “to desolation; nearly all her looms ceased rattling on one and the same day, and the streets of her cities, but lately filled with rich and busy workmen, were overrun with beggars who asked in vain for work to escape from misery and hunger.” The English land-owners and farmers did not suffer so much, but were scarcely less angered; only it was to the King of France and the Count of Flanders rather than their own king that they held themselves indebted for the stagnation of their affairs, and their discontent sought vent only in execration of the foreigner.

Читать дальше