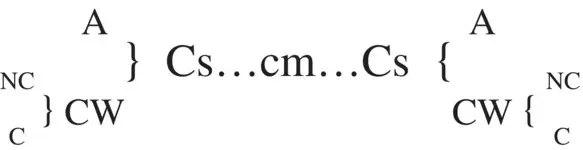

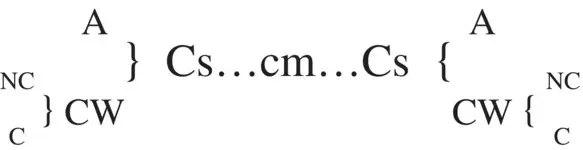

Figure 3.1 The Circuit of the Commons.

Source: DeAngelis, M. (2017). Omnia sunt communia: On the commons and the transformation to post‐capitalism. London: Zed Books.

Within commons‐based peer production, we also have numerous examples of the ways in which communities negotiate their relationship with capitalist firms. One notable example of how this is done is through the creation of “boundary organizations,” which are established to negotiate and establish boundaries between two parties who may have both disparate and shared interests (O’Mahony & Bechky, 2008). Within free and open source software development, communities working on free software projects want to ensure the survival of their software projects and attract other developers to work on the project, and securing corporate sponsorship of a project can be a direct way of attracting more developers to the project (Santos, Kuk, Kon, & Pearson, 2013). However, the community also has an interest in preserving its creative autonomy by not ceding too much influence or power to the corporation. One example of a boundary organization is the Fedora Project Board, which negotiates the boundaries between the Fedora Project as a free software project and Red Hat, Inc. as its corporate sponsor (see Birkinbine, 2017).

These examples illustrate the tension that lies at the heart of peer production and the commons. On the one hand, communities want to ensure creative autonomy for their members as well as the survival of their common resources over time. On the other hand, commons‐based peer production provides an intriguing opportunity for capitalist firms looking to extract value from the community’s productive activities. Indeed, commons‐based peer production has proven to be an efficient and effective model of production, even producing large‐scale projects like the Linux kernel, which contains millions of lines of software code (see The Linux Foundation, 2019). When firms want to harness the production power of commons‐based communities, they often need to find ways of negotiating access to those communities, particularly because their interests may differ from those of the community.

This chapter has provided an overview of the political economy of peer production. I began with an examination of the structural changes within capitalism that enabled the rise of peer production, and I also focused on some of the emergent cultural practices of peer production that subvert prevailing tendencies of capitalism. As such, there is a tension between capital and the commons that is constantly at play in the political economy of peer production. In this sense, it is useful to understand peer production as dialectically situated between capital and the commons, as it can account for the contradictory power of peer production, highlighting the ways that peer production intersects with circuits of capital accumulation but also the ways in which value is created and circulates within peer production communities according to a different logic. On the one hand, the extraction of value from data and information provided gratis to corporations has been a boon to capital accumulation schemes – certainly as it pertains to rapid growth and the attraction of speculative financial capital, if not proven formulas for profitability. On the other hand, peer production enables the creation of digital commons that can be shared with an increasingly large online community. The production, maintenance, and reproduction of the commons over time also carries the possibility of ushering in an era where mutual aid, care, trust, conviviality, and the commonwealth are valued more than competition, exploitation, and the maximization of individual or corporate profit.

1 Abbate, J. (1999). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

2 Andrejevic, M. (2007). ISpy: Surveillance and power in the interactive era. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

3 Andrejevic, M. (2012). Exploitation in the data mine. In C. Fuchs, K. Boersma, A. Albrechtslund, & M. Sandoval (Eds.), Internet and surveillance: The challenges of web 2.0 and social media (pp. 71–88). New York, NY: Routledge.

4 Bauwens, M., & Niaros, V. (2017). Value in the commons economy: Developments in open and contributory value accounting [PDF file]. Retrieved from www.boell.de/sites/default/files/value_in_the_commons_economy.pdf

5 Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

6 Birkinbine, B. J. (2017). From the commons to capital: Red Hat, Inc. and the business of free software. Journal of Peer Production, 10. Retrieved from http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue‐10‐peer‐production‐and‐work/from‐the‐commons‐to‐capital/

7 Boltanski, L., & Chiapello, E. (2005). The new spirit of capitalism. London: Verso.

8 Brenner, R. (2006). The economics of global turbulence. London: Verso.

9 Cassidy, J. (2002). Dot.con: How America lost its mind and money in the Internet era. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

10 Cohen, N. (2016). Writer’s rights: Freelance journalism in a digital age. Montreal: McGill‐Queen’s University Press.

11 Coleman, E. G. (2013). Coding freedom: The ethics and aesthetics of hacking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

12 Colley, J. (2019, January 11). Why 2019 could be the year of another tech bubble crash. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/why‐2019‐could‐be‐the‐year‐of‐another‐tech‐bubble‐crash‐109468

13 Dalla Costa, M., & James, S. (1975). The power of women and the subversion of the community. Bristol: Falling Wall Press.

14 DeAngelis, M. (2017). Omnia sunt communia: On the commons and the transformation to post‐capitalism. London: Zed Books.

15 Deuze, M. (2007). Media work. Cambridge: Polity.

16 Drucker, P. F. (1994). Post‐capitalist society. New York, NY: HarperBusiness.

17 Dyer‐Witheford, N. (2006). The Circulation of the Common. Paper presented at Immaterial Labour, Multitudes and New Social Subjects: Class Composition in Cognitive Capitalism conference. University of Cambridge.

18 Federici, S. (2012). Revolution at point zero: Housework, reproduction, and feminist struggle. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

19 Fuchs, C. (2011, February 1). New media, web 2.0 and surveillance. Sociology Compass, 5(2), 134–147.

20 Fuchs, C. (2012). Critique of the political economy of web 2.0 surveillance. In C. Fuchs, K. Boersma, A. Albrechtslund, and M. Sandoval (Eds.), Internet and surveillance: The challenges of web 2.0 and social media (pp. 31–70). New York, NY: Routledge.

21 Gaither, C., & Chmielewski, D. C. (2006, July 16). Fears of dot‐com crash, version 2.0. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/2006/jul/16/business/fi‐overheat16

22 Gutiérrez‐Aguilar, R. (2014). Beyond the “capacity to veto”: Reflections from Latin America on the production and reproduction of the common. South Atlantic Quarterly, 113(2), 259–270.

23 Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2000). Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

24 Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2004). Multitude: War and democracy in the age of empire. New York, NY: Penguin.

25 Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2009). Commonwealth. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

26 Harvey, D. (1989). The condition of postmodernity: An enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Oxford: Blackwell.

27 Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Справочник Гименея [The Handbook of Hymen]](/books/407356/o-genri-spravochnik-gimeneya-the-handbook-of-hymen-thumb.webp)