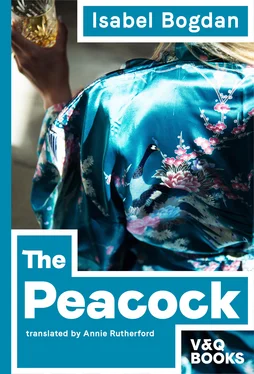

Isabel Bogdan was born in Cologne and studied English and Japanese. She is an enthusiastic Hamburg-dweller, reader, writer and translator into German (including Jane Gardam, Jonathan Safran Foer, Nick Hornby, Jasper Fforde). Her first book Sachen Machen came out in 2012, followed in 2016 by The Peacock , and in 2019 by Laufen . She has won prizes for her translating, her writing and the online interview project “Was machen die da?”

Annie Rutherford champions poetry and translated literature in all its guises. She works as Programme Co-ordinator for StAnza, Scotland’s international poetry festival, and as a writer and translator. Her published translations include German/Swiss poet Nora Gomringer’s Hydra’s Heads (Burning Eye Books, 2018) and Belarusian poet Volha Hapeyeva’s In My Garden of Mutants (Arc, 2021). She co-founded the literary magazine Far Off Places and Göttingen’s Poetree festival.

Isabel Bogdan

Translated from the German by Annie Rutherford

|

Co-funded by the Creative Europe programme of the European Union |

V&Q Books, Berlin 2021

An imprint of Verlag Voland & Quist GmbH

First published in the German language as Der Pfau by Isabel Bogdan

© 2016 Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch GmbH & Co. KG, Cologne/Germany

All rights reserved

Translation copyright © Annie Rutherford

Editing: Katy Derbyshire

Copy editing: Angela Hirons

Cover photo © Dorit Guenter

Cover design: Pingundpong*Gestaltungsbüro

Typesetting: Fred Uhde

ISBN: 978-3-86391-293-2

eISBN 978-3-86391-308-3

www.vq-books.eu

For Jeannie and Hector Maclean

Über den Autor Isabel Bogdan was born in Cologne and studied English and Japanese. She is an enthusiastic Hamburg-dweller, reader, writer and translator into German (including Jane Gardam, Jonathan Safran Foer, Nick Hornby, Jasper Fforde). Her first book Sachen Machen came out in 2012, followed in 2016 by The Peacock , and in 2019 by Laufen . She has won prizes for her translating, her writing and the online interview project “Was machen die da?” Annie Rutherford champions poetry and translated literature in all its guises. She works as Programme Co-ordinator for StAnza, Scotland’s international poetry festival, and as a writer and translator. Her published translations include German/Swiss poet Nora Gomringer’s Hydra’s Heads (Burning Eye Books, 2018) and Belarusian poet Volha Hapeyeva’s In My Garden of Mutants (Arc, 2021). She co-founded the literary magazine Far Off Places and Göttingen’s Poetree festival.

The Peacock

Translator’s Note

One of the peacocks had gone mad. Or maybe he just couldn’t see very well. At any rate, he suddenly regarded anything blue and shiny as competition on the marriage market.

Luckily, there were very few blue and shiny things in the little glen at the foot of the Highlands. There were fields and meadows and trees and altogether a great deal of green, and there was the heather. And any number of sheep. The only shiny blue things which occasionally strayed there were the holidaymakers’ cars. Lord and Lady McIntosh had converted the former farm buildings, barns and anything else vaguely suitable which belonged to their estate into holiday cottages, so that the old place recovered at least some of the money it gobbled up. The oldest parts of the castle presumably dated back to the seventeenth century, when the castle had been built, and there had been various annexes and extensions over the following centuries. There hadn’t always been enough money for ongoing modernisations, and this remained the case today. The house cost money. The plaster would flake off the facade and need replacing, and then a water pipe would burst, or the roof would need repairing. Lady Fiona mainly repaired the electrics herself, because hardly any electricians nowadays can still cope with 110 volts or deal with the old fuses. The heating costs regularly brought the McIntoshes out in a sweat, which is more than could be said of the temperatures in the house. The ground floor was paved with flagstones, so it was never particularly warm, even in hot summers, and hot summers were rare. In winter it was even colder. There was a central heating system which didn’t deserve the name, and so most rooms were simply cold. Only the kitchen was always pleasant, with a fire burning constantly in the old Aga. Almost all year round, the Laird and Lady spent their evenings by the fireplace in the library, where they read, worked or watched DVDs. In winter they sometimes wore woolly hats to bed. They didn’t mind, they were used to it. When they were frozen through, they took a bath or got into the hot tub outside on the great lawn.

Lord McIntosh sometimes joked that he might as well go ahead and try to insulate the house with banknotes. The Laird was a classics scholar and didn’t understand much about buildings. The Lady was an engineer and understood rather more, despite working for a wind turbine company. They’d both mastered the basics of addition and subtraction. They weren’t poor, they had more than enough to live on but not enough for a thorough renovation of the old property.

The cottages had only slightly more modern facilities – they were somewhat better insulated and had carpets and low ceilings, so they were considerably easier to heat. And of course, every bed had an electric blanket. It was really quite cosy in the former gatehouse a mile and a half away by the entrance to the drive, in the gardener’s house on the other side of the wee river, in the washhouse half a mile up the glen, in the former stables beyond the woods, and in the other cottages dotted around further away in the glen, next to gravel roads or at the ends of muddy tracks. You visited your next-door neighbours by car here, and if you were drunk on the way home, it didn’t matter too much because you were unlikely to meet another car or get pulled over. If you landed in a ditch, there were enough tractors which could pull you out again. The so-called village was made up of a handful of houses, a tiny church, and a telephone box nobody had used for years.

Renting out the cottages was going quite well, people loved the peace and quiet and the nature. Getting away from everything, no phone signal, no TV, just the murmur of the stream. They mostly came in the summer, often middle-aged couples who worked long hours back home and would mainly go for walks here, or families with children. Life was less hurried here than in the city. The nearest town was twelve miles away.

In a fit of exuberance one day, Lord McIntosh had purchased five peacocks, three females and two males; he had imagined how pretty it would be when the males strutted around the great lawn in front of the house, fanning out their trains. The less attractive females were to stay quietly in the background, discreetly giving the males a reason to compete and fan their tail feathers in the first place. That’s how he’d pictured it. Lord McIntosh was very keen on animals in general, but he didn’t understand very much about them.

Читать дальше