The evening before our friend left us, Coleridge had a long conversation with her on serious and religious subjects. Fearing, however, that he might not have been clearly understood, he the next morning brought down the following paper, written before he had retired to rest: —

‘S. T. Coleridge’s confession of belief; with respect to the true grounds of Christian morality’, 1817.

1. I sincerely profess the Christian faith, and regard the New Testament as containing all its articles, and I interpret the words not only in the obvious, but in the ‘literal’ sense, unless where common reason, and the authority of the Church of England join in commanding them to be understood FIGURATIVELY: as for instance, ‘Herod is a Fox.’

2. Next to the Holy Scriptures, I revere the Liturgy, Articles, and Homilies of the Established Church, and hold the doctrines therein expressly contained.

3. I reject as erroneous, and deprecate as ‘most’ dangerous, the notion, that our ‘feelings’ are to be the ground and guide of our actions. I believe the feelings themselves to be among the things that are to be grounded and guided. The feelings are effects, not causes, a part of the ‘instruments’ of action, but never can without serious injury be perverted into the ‘principles’ of action. Under ‘feelings’, I include all that goes by the names of ‘sentiment’, sensibility, &c. &c. These, however pleasing, may be made and often are made the instruments of vice and guilt, though under proper discipline, they are fitted to be both aids and ornaments of virtue. They are to virtue what beauty is to health.

4. All men, the good as well as the bad, and the bad as well as the good, act with motives. But what is motive to one person is no motive at all to another. The pomps and vanities of the world supply ‘mighty’ motives to an ambitious man; but are so far from being a ‘motive’ to a humble Christian, that he rather wonders how they can be even a temptation to any man in his senses, who believes himself to have an immortal soul. Therefore that a title, or the power of gratifying sensual luxury, is the motive with which A. acts, and no motive at all to B. — must arise from the different state of the moral being in A. and in B. — consequently motives too, as well as ‘feelings’ are ‘effects’; and they become causes only in a secondary or derivative sense.

5. Among the motives of a probationary Christian, the practical conviction that all his intentional acts have consequences in a future state; that as he sows here, he must reap hereafter; in plain words, that according as he does, or does not, avail himself of the light and helps given by God through Christ, he must go either to heaven or hell; is the ‘most’ impressive, were it only from pity to his own soul, as an everlasting sentient being.

6. But that this is a motive, and the most impressive of motives to any given person, arises from, and supposes, a commencing state of regeneration in that person’s mind and heart. That therefore which ‘constitutes’ a regenerate STATE is the true PRINCIPLE ON which, or with a ‘view’ to which, actions, feelings, and motives ought to be grounded.

7. The different ‘operations’ of this radical principle, (which principle is called in Scripture sometimes faith, and in other places love,) I have been accustomed to call good impulses because they are the powers that impel us to do what we ought to do.

8. The impulses of a full grown Christian are 1. Love of God. 2. Love of our neighbour for the love of God. 3. An undefiled conscience, which prizes above every comprehensible advantage ‘that peace’ of God which passeth all understanding.

9. Every consideration, whether of hope or of fear, which is, and which ‘is adopted’ by ‘us’, poor imperfect creatures! in our present state of probation, as MEANS of ‘producing’ such impulses in our hearts, is so far a right and ‘desirable’ consideration. He that is weak must take the medicine which is suitable to his existing weakness; but then he ought to know that it is a ‘medicine’, the object of which is to remove the disease, not to feed and perpetuate it.

10. Lastly, I hold that there are two grievous mistakes, — both of which as ‘extremes’ equally opposite to truth and the Gospel, — I equally reject and deprecate. The first is, that of Stoic pride, which would snatch away his crutches from a curable cripple before he can walk without them. The second is, that of those worldly and temporizing preachers, who would disguise from such a cripple the necessary truth that crutches are not legs, but only temporary aids and substitutes.”

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner

Table of Contents

Part the First.

Part the Second.

Part the Third.

Part the Fourth.

Part the Fifth.

Part the Sixth.

Part the Seventh.

Table of Contents

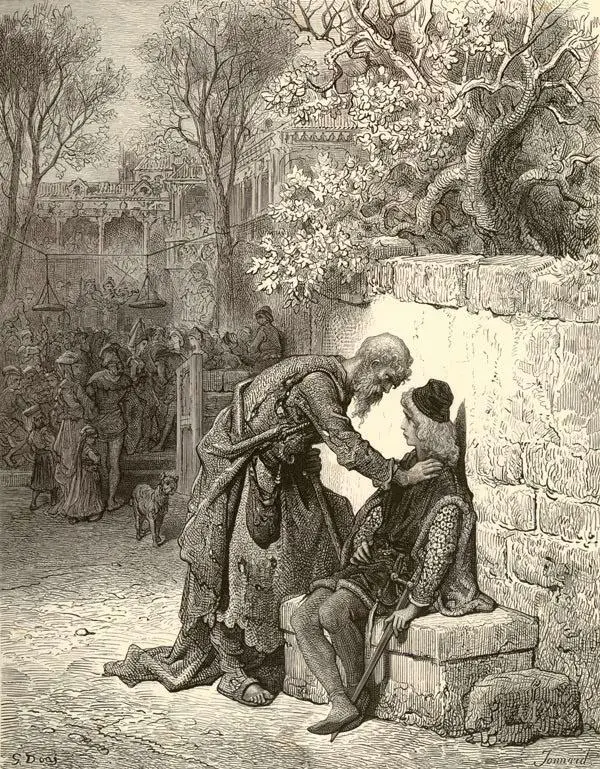

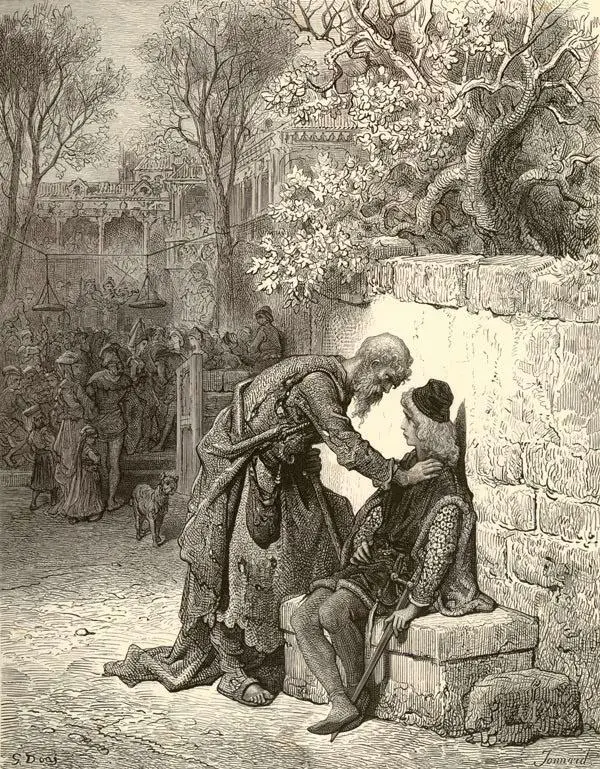

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

“By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

“The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May’st hear the merry din.”

Wherefore stopp'st thou me?

Wherefore stopp'st thou me?

He holds him with his skinny hand,

“There was a ship,” quoth he.

“Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard loon!”

Eftsoons his hand dropt he.

He holds him with his glittering eye —

The Wedding–Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding Guest

The Wedding Guest

The Wedding–Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot chuse but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the light-house top.

The Sun came up upon the left,

Out of the sea came he!

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the sea.

Higher and higher every day,

Till over the mast at noon —

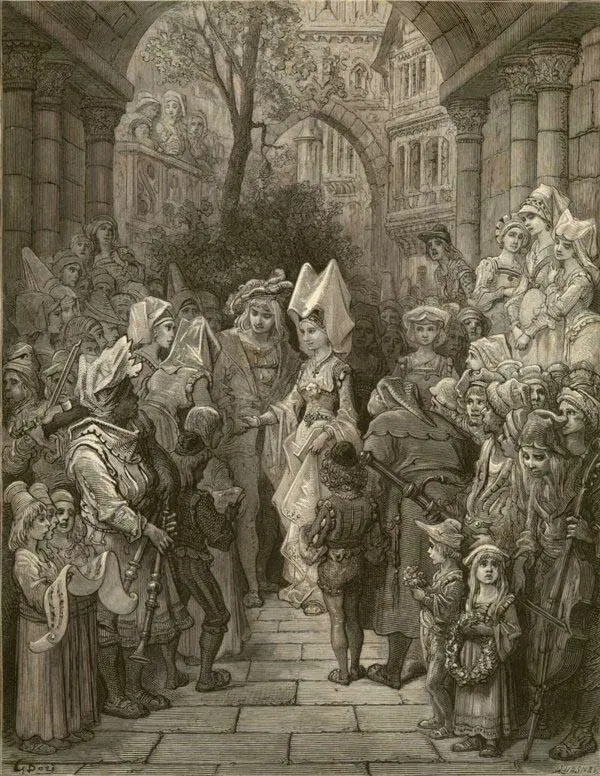

The Wedding–Guest here beat his breast,

For he heard the loud bassoon.

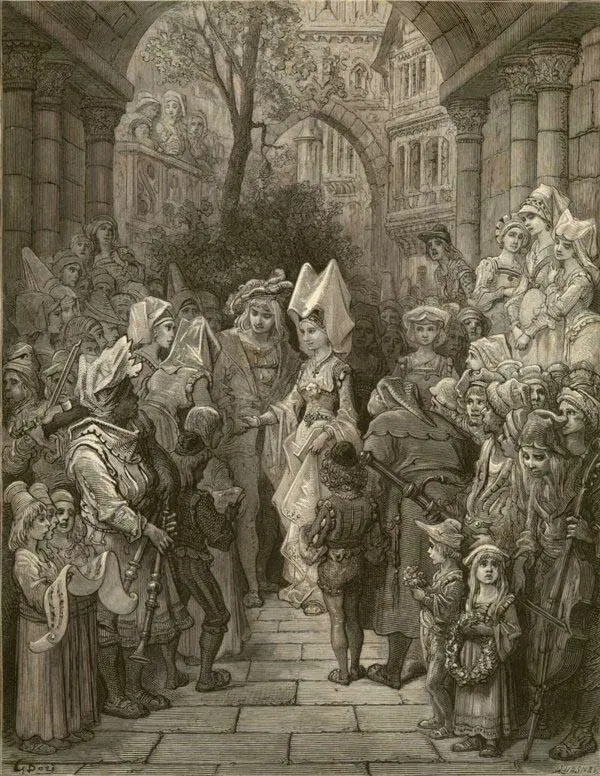

Red as a Rose is the Bride

Red as a Rose is the Bride

The bride hath paced into the hall,

Red as a rose is she;

Nodding their heads before her goes

The merry minstrelsy.

The Wedding–Guest he beat his breast,

Yet he cannot chuse but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

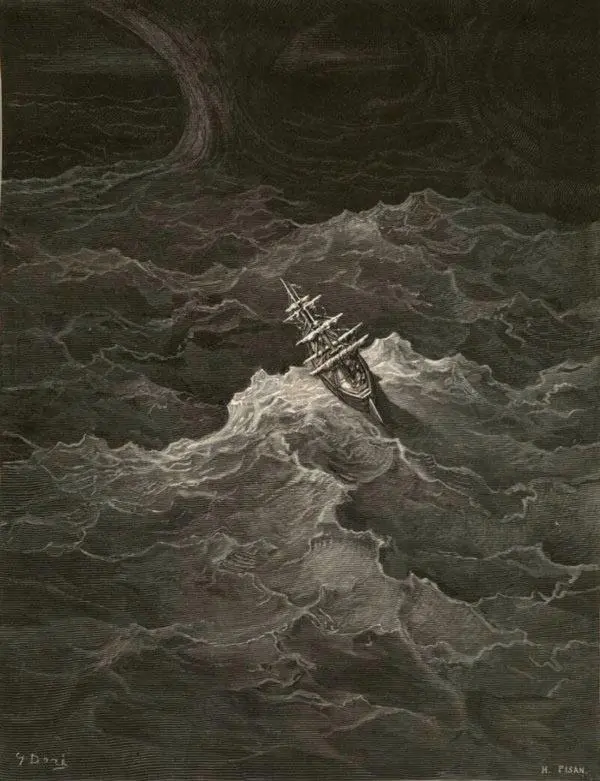

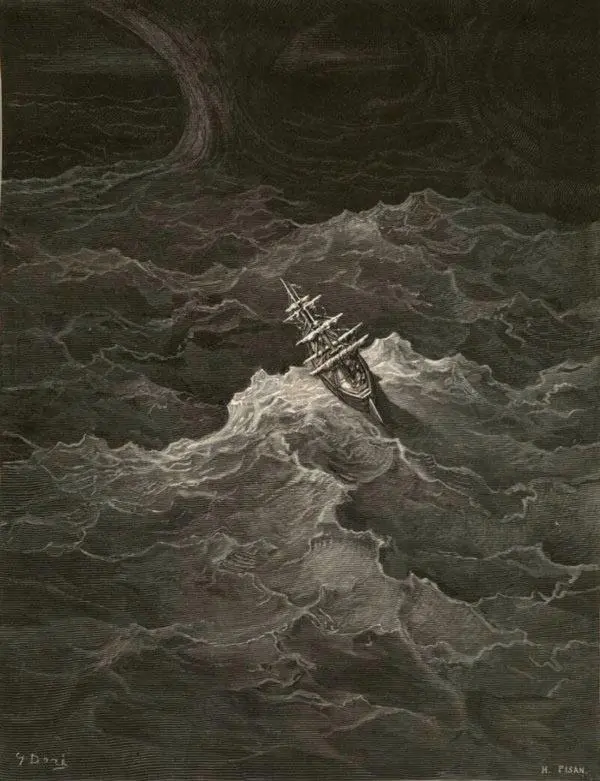

And now the STORM-BLAST came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong:

He struck with his o’ertaking wings,

And chased south along.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yell and blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

And southward aye we fled.

The Ship Fled the Storm

The Ship Fled the Storm

Читать дальше

Wherefore stopp'st thou me?

Wherefore stopp'st thou me? The Wedding Guest

The Wedding Guest Red as a Rose is the Bride

Red as a Rose is the Bride The Ship Fled the Storm

The Ship Fled the Storm