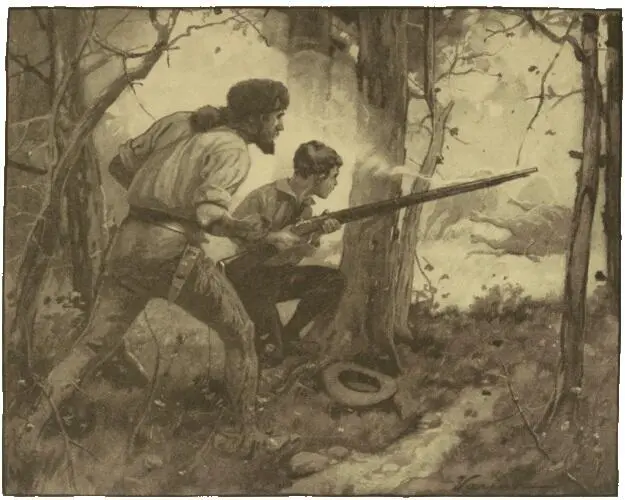

But nothing could have induced me to admit that I felt so; gritting my teeth, I followed on uncertain legs, close at Uncle Wesley's heels. So close was I that when he suddenly stopped, I bumped into him, and then gave a little squeal of fright, for I thought that he had discovered something to justify my fears.

" Sh-h-h-h! " he cautioned, and reaching back and drawing me to his side, he pointed significantly ahead.

We were only a few yards from the outer edge of the timber; a hundred yards farther on were three buffalo bulls, standing motionless on the open, sparsely grassed bottom-land. How big they were! How majestic and yet uncouth they loomed before me! They had apparently no necks at all. Forgetting entirely our purpose in coming there, I stared at them with intense interest, until my uncle passed me the rifle and whispered, "Take that farthest one. He is young and in good condition. Aim low, close behind his shoulder."

My hands closed on the long-barreled, heavy weapon. Heretofore my boy strength had been sorely taxed to shoot with it, but now, in my tense excitement, it fairly leaped to my shoulder, and I was able to hold it steady. I pulled the trigger.

Bang! A thick cloud of powder smoke drifted into my face, and then passed on, and I saw two of the bulls running across the bottom; the other was swaying, staggering round and round, with blood streaming from its mouth. Before I could reload, it toppled over with a crash and lay still.

It toppled over with a crash and lay still.

I stood staring at the animal like one in a dream; it was hard to realize that I had actually killed it. Uncle Wesley broke my trance by praising the shot I had made, and added that the animal was in fine condition and would weigh all of a ton. He had me lie down on it, my feet even with its fore feet, and I found that I could not reach the top of its withers, or rather, its hump: its height had been more than six feet.

I now got my first lesson in skinning and butchering one of these great animals. Without axe or windlass, or any of the other things regarded as indispensable by farmers and by professional butchers, the old-time plainsmen made a quick and neat job of this work with only a common butcher-knife.

First, my uncle doubled up the bull's fore legs and straightened back the hind ones. Then, little by little, he twisted the great head sharply back beside the body, at the same time heaving up the back, and in a moment or two the animal lay prone on its belly, propped up in that position by the head. If the skin had been wanted, the rolling-up of the animal would have been reversed, and it would have lain on its back, legs up, and as in the other way, propped in position by the bent-back head.

After making an incision along the back from head to tail, he skinned both sides down to the ground, and even under the body, by propping the head one way and then another, and slanting the carcass so that there was knife room beneath. At last the body lay free, back up, on the clean, spread-out skin.

The choicest part of it was the so-called "hump," or in frontier language, the "boss ribs." These dorsal ribs rose gradually from the centre of the back to a length of twenty inches and more just above the point of the shoulders, and were deeply covered with rich tenderloin.

It took but a moment to get the set off. Uncle Wesley cut an incision along each side at the base of them; then he unjointed a hind leg at the gambrel-joint, and with that for a club he hit the tips of the ribs a few blows, causing them to snap off from the back-bone like so many pipe-stems, and the whole hump lay free on the hide.

Next, he removed the legs with a few deft cuts of the knife, and laid them out on the clean grass; unjointed the backbone at the third rib and removed the after part; severed the neck from the big ribs, cut them apart at the brisket, and smashed one side of them free from the backbone with the leg club, and there we had the great animal divided in eight parts. Lastly, he removed the tongue through an incision in the lower jaw.

"There," said he, when it was all done, "now you know how to butcher. Let's hurry to the boat and get the roustabouts to carry in the meat."

From this point on, there were days at a time when we saw no Indians, and the various kinds of game animals were more and more plentiful and tame. At last, several days after passing Fort Clarke, we came to the American Fur Company's greater post, Fort Union, situated on the north bank of the river about five miles above the mouth of the Yellowstone.

It was begun in 1829, under the direction of the factor, Kenneth McKenzie, and finished in 1832. A stockade of logs ten or twelve feet long, set up on end, side by side, protected the buildings, and this, in turn, was commanded by two-storied bastions, in which cannon were mounted at the northeast and southwest corners.

When we approached the place, a flag was run up on the staff of the fort, cannon boomed a welcome, and a great crowd of Indians and company men, headed by the factor, gathered at the shore to greet us. My uncle and I were escorted to the two-story house which formed the rear of the fort, and in which were the quarters of the factor and clerks.

I learned afterward that distinguished guests had been housed there: George Catlin, the painter and philanthropist, in 1832; Maximilian, Prince of Neuwied, in 1833; and Audubon, the great naturalist, in 1843. All of them published extremely interesting accounts of what they saw and did in the Upper Missouri country, which I commend to the reader, Maximilian's "Travels in North America" especially; for I went up the river from Fort Union just as he did, and there had been practically no change in the conditions of the country from his time to mine. Maximilian gives a wonderfully accurate and vivid description of the remarkable scenery of the Missouri, without question the most strangely picturesque river in America, and probably in the world.

My Uncle Wesley was a valued clerk of the American Fur Company. He was sent from one to another of their Far Western forts, as occasion for his services arose, and frequently he was in full charge of a post for months at a time, while the factor went on a trip to the States. When we arrived in Fort Union he was told that he must go on to Fort Benton, where the factor needed his help. At that time, since the company's steamboats went no farther than Fort Union, all the goods for the posts beyond were sent in keel-boats, or bateaux. It was not until the summer of 1860 that the extreme upper river was found to be navigable, and on July 2 of that year the Chippewa and the Key West arrived at Fort Benton.

A keel-boat was lying at Fort Union when we arrived there; it was waiting for part of the Chippewa's cargo of ammunition, guns, and various trade goods, mostly tobacco, red and blue cloth, brass wire for jewelry, Chinese vermilion, and small trinkets. These were soon transferred, and we resumed our voyage, Uncle Wesley in charge of the boat and crew. The Minnie was sixty feet long, ten feet wide, and was decked over. The crew consisted of thirty French-Canadian cordelliers, or towmen, a cook, a steersman and two bowmen, and a hunter with his horse. In a very small cabin aft there were two bunks. Forward there was a mast and sail for use when the wind was favorable—which was seldom. There was a big sweep oar on each side, and a number of poles were scattered along the deck to be used as occasion required. In the bow there was a four-pound howitzer, loaded with plenty of powder, and a couple of quarts of trade balls, in case of an attack by Indians, which was not at all improbable.

Читать дальше