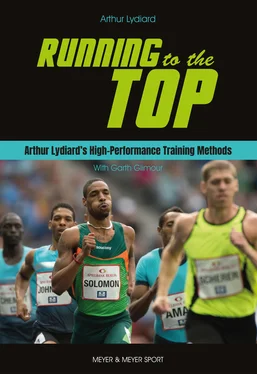

Of the Lydiard system, Daws wrote: ”A few aspiring kids approach a neighbourhood shoemaker to teach them to run. The shoemaker is a high school drop-out and retired distance runner whose own brand of torturous training methods have so far earned him little more than scorn and ridicule from the coaching community. He agrees to help and, although the runners are not the country’s best, not even the city’s best – just eager kids from the neighbourhood – the shoemaker promises them world records and Olympic medals if they can endure the workouts. The boy the shoemaker first publicly predicts will set a world record is crippled in one arm; and another runner, who the shoemaker says will be the best middle-distance runner ever, looks muscle-bound and awkward.

”A few years later, the country’s entire contingent of distance runners to the 1960 Olympics is coached by the former shoemaker. Thirty minutes apart, the crippled one and the awkward one win gold medals; a day later, another of his runners, seemingly athletically nondescript, takes a bronze. From these and other of the shoemaker’s pupils come most of the world records from 800 metres to the one-hour run and two more golds and a bronze in the next Olympics. Wild dreams? A fairy tale? Hardly, I’m just recounting the emergence of New Zealand’s Arthur Lydiard, guru of distance runners, father of the jogging craze, prime mover and motivator of Olympians world-wide … Lydiard has either directly coached or influenced more world record-holders and Olympics medalists than anyone. With seemingly endless energy, he has lectured up one country and down another, pausing periodically to serve as national coach in Finland, Denmark, Mexico and Venezuela. Ironically, he is, like many prophets, largely ignored in official circles in his own country.“

”When Peter Snell and Murray Halberg sprinted off with the gold in the 800 and 5,000 and Barry Magee won the marathon bronze in the 1960 Rome Olympics, the rest of the world was full swing into interval training. So ingrained is the Lydiard philosophy now, we almost have to force ourselves to recall that before him, the coaching of distance runners was aimed 180 degrees in the other direction. Lydiard was the beginning of a magic era; jogging became acceptable if not godlike … Lydiard was the keystone and he never lets us forget that, as an unschooled layman, he did what physiologists, theorists and professional coaches hadn’t been able to do. He was unsophisticated but he was smart and he had the tenacity of a bulldog.“

It was the Lydiard approach that turned my career around and it is the basis for my concept of efficient training. Lydiard’s methods are not geared towards immediate results. He speaks of progressing over several years and sacrificing early success to lay the groundwork for bigger victories later. Even within each season, you would not reach your peak until the last possible moment. Both of these concepts are implied when Lydiard wrote: ”You will come to your peak slower than many others and you will be running last when they are running first. But when it is really important to be running first, you will be passing them.“

The March/April 1992 issue of Peak Running Performance , a US publication which presents running-related research information, was entirely devoted to a study of Lydiard’s running philosophy.

”His legacy“, it said, ”can be seen in the training schedules of most of the world’s best middle- and long-distance runners. While Lydiard’s coaching days ended about a quarter-century ago, his breakthrough approach to training remains securely embedded.

”After his great coaching successes at the 1960 and 1964 Olympic Games, sports scientists and exercise physiologists around the world confirmed the scientific soundness of his methods. While Lydiard was not a scientist, his overall training approach was well ahead of the scientific community of his day.“

Lydiard’s programme epitomises one general but very critical concept related to exercise and sports physiology. This broad principle is gradual adaptation. While most athletes would call this “plain old common sense“, experience tells us that common sense is not so common – especially among runners who have a strong desire to improve their running.

The magazine illustrates the concept with the legend of the Greek strongman who lifted a calf when it was first born and continued to lift it each day until it was a full-grown cow. The day-to-day increase in weight was hardly noticeable although the increase over time was significant. With the Lydiard system, it says, this process of gradual adaptation can produce astounding long-term results.

Garth Gilmour

Twenty-one factors influence the running athlete. Some are factual, some physical, the rest mental. All of them play a part in how well an athlete performs, how successfully he or she can reach whatever level of achievement he or she aspires to.

They are:

1.The date of the race

2.The challenge the race represents

3.Age

4.Talent

5.Health

6.Nutrition

7.Drugs

8.Hormones

9.Body build

10.Running technique

11.Aerobic capacity

12.Weight

13.Body fat

14.Training methods

15.Coaching

16.Tactics

17.Self-discipline

18.Track conditions

19.State of the weather

20.The opposition

21.The balance between aerobic and anaerobic exercise

Some of them appear under more than one heading. For instance, your weight and body fat at any given time are facts but they are also physical conditions which can be altered. And there are some physical conditions which are susceptible to mental influences or can influence mental attitudes. Each is an integral part of the whole athlete and his or her personal encyclopedia of knowledge.

We have not given them any order of priority because none exists but, perhaps, the single most important factor of them all is the first listed – the date of the competition.

Think about it. You do not have to be an Einstein to see how significant that race date is. Whether the race is a club championship, a national title event or an Olympic Games final, everything that happens in the lead-up to it – and we’re talking from weeks to years depending on the individual athlete’s level of experience and ambition – is aimed at that single event. Anything else along the way is merely a stepping stone to the ultimate goal.

So, everything the athlete does in that lead-up has to be timed correctly and precisely to produce the peak performance when the starting gun sounds on the big day. If you doubt that, listen to any group of athletes talking after a championship.

They are noted for their excuses after events. A lot of Olympic titles were won in times that very many competitors had comfortably bettered. Yet, on the day, they cannot perform anywhere near their best.

This demonstrates that the race date is indeed the key to correct training. I often tell young people, “Look, last year, you ran the best race of your career. Everything went right and you performed at your very best. Now, if you know why that happened and you put your training plan together properly to reproduce that peak performance again on the day of the first race you want to win this season, then I would say you know something about training.

“Until you can do that, you don’t know a damn thing about it. You are just a good athlete who, one day, without realising why it is happening, will run a good race.“

Читать дальше