1. Sir George Cayley’s Aeronautics 1796-1855 , by Charles H. Gibbs-Smith (Science Museum, London, 1962).

2. Smeaton disclosed his tables of pressures around 1750, after an extended visit to the Low Countries where he was able to observe the windmills there and their efficient wing-shapes, a result of centuries of practical experience.

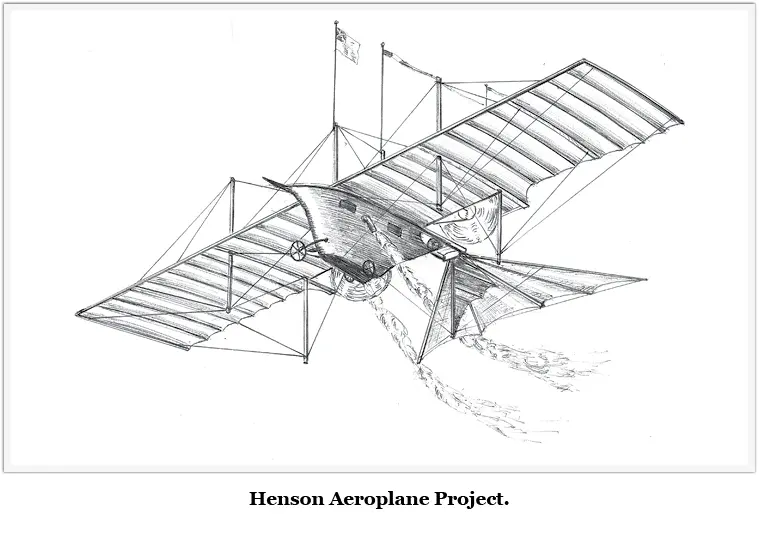

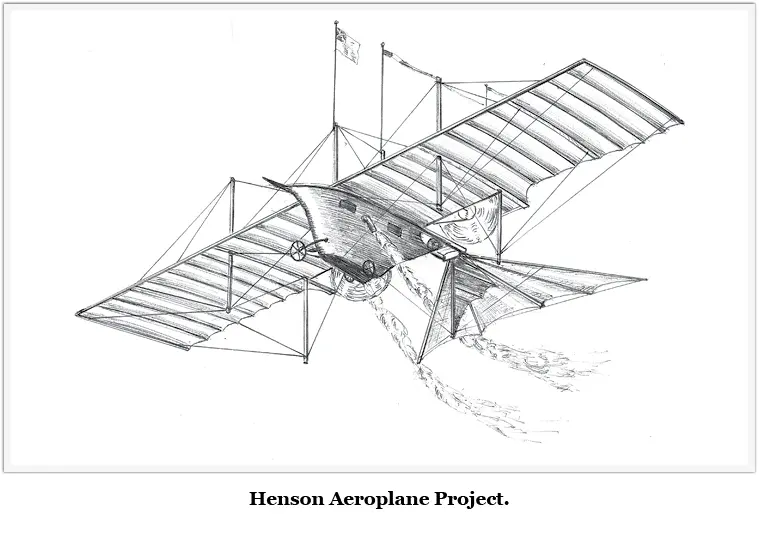

Henson and Stringfellow

The weight of the man-carrying machine was estimated by Cayley to be about 500 lbs, complete with engine and propeller. He thus arrived at a requirement of 10 hp for every 1000 lbs lifted. This fired the imagination of William Samuel Henson to such an extent that in 1843 he proposed an “Aerial Transit Company” bill in the House of Commons.

His object was the construction of a flying machine powered by a steam engine developing 25 to 30 hp and weighing over 600 lbs. The complete aeroplane would weigh about 3000 lbs with a wing surface of 6000 sq ft. This would, in Henson’s opinion, enable him to organize aerial transit to several distant points of the globe.

Henson’s proposals received a great deal of publicity but, if he had ever been given the green light to proceed with his Transit Company, the business would have floundered because of the lack of adequate power, as well as by the enormous surface requirement of the wing and the tail.

But Henson and his engineering associate John Stringfellow went to work anyway on small-scale models. If there is one thing that continually amazes the historian, it is the optimism with which the early pioneers tackled the host of difficulties that lay before them.

Henson realized that high steam pressures would be required so he set to and designed and built a model engine to work on a pressure of 100 lbs/sq in. After many discouraging years without result, Henson gave up in 1849, whilst Stringfellow continued alone and was at last able to build a small model steam engine which was said to produce about one-third hp for a weight of 13 lbs, including the steam generator.

France takes up the challenge

After Henson’s experiments, aviation in the UK was allowed to lapse but, curiously enough, interest in dynamic flight arose again in France, in spite of Navier’s calculations, which could have been forgotten in the meantime.

It is significant to note that Cayley was asked to contribute and he subsequently wrote several articles for the Bulletin Trimestriel of the first aeronautical society in the world, the Société Aérostatique et Météorologique de France , founded by a well-known French aeronaut J. F. Dupuis Delcourt. As will be noted, the title does not mention dynamic flight.

Yet Cayley, in 1853, proposed rather slyly that “As aerial navigation on the balloon principle, can only be carried out on an enormous scale of magnitude and expense ... it may not be unworthy of the Society to turn its attention towards making some cheap preliminary experiments to ascertain practically what can be done on the principle of the inclined plane, which appears to be applicable on any small scale from that of a bird to the uses of man, ... whenever a first mover, combining sufficient power, within a certain limit as to weight, is discovered.”

There is no evidence that directly links Cayley’s articles and proposals in this French Bulletin to the first attempts by Frenchmen to start experiments with fixed-wing aeroplanes, but the analogies are striking.

In 1857, a French naval officer, Félix du Temple, patented a fixed-wing flying machine moved by a motor. The machine was calculated to weigh one ton and du Temple, with more optimism than Cayley’s, estimated the power requirement as 6 hp.

Du Temple’s machine had a tail in the rear and a slight dihedral of the monoplane wing. One interesting original feature was the proposal that the aeroplane should take off by rolling across a field in the modern manner. Due consideration was also given to the question of stability.

Experiments were on small-scale models but, as soon as full-scale construction began around 1874, “the inadequacy of all motors known became apparent” as O. Chanute wrote. Du Temple had experimented with steam at high pressures and in due course designed an efficient boiler consisting of small water tubes as advocated by Cayley in 1809. This boiler produced no flight, but it was adopted by the French Navy, so du Temple was in some measure rewarded for his pains.

A second experimenter was Joseph Pline, a pioneer of great originality, who presented a patent in 1855 using a fixed plane in conjunction with a balloon, in an effort to get the best of both aeronautical systems. One interesting feature in this patent was that the fixed plane was for the first time designated with the word aéroplane .

Pline’s mixed system was not built; it would have been a failure as were all others that followed, trying to add wings to an airship, but Pline soon began to experiment with small flying models and stated that he was certain that it was possible for a plane to rise, sustain itself and fly around in the atmosphere without the use of hydrogen.

After carefully observing aerial currents as well as the organs used for flight by different animals (nature has produced more flying creatures than earthbound ones), Pline came to the conclusion that curved surfaces were the most efficient and he designed several paper models that had wings consisting of half-cylindrical surfaces arranged in the direction of flight, somewhat in the manner of F. M. Rogallo’s flexible wings designed in 1948.

Pline’s model aeroplanes flew gracefully and, under the name Papillons de Pline (Pline’s Butterflies), acquired great fame in France during the 1860s. All aeronautical experimenters were able to witness the flights of these flying models, which proved that in case of engine failure, a fixed-wing machine would not fall like a stone but could glide safely to earth.

The fruitful decade

Human progress sometimes proceeds by leaps and bounds and the 1860s and 1870s were a case in point in the field of flight. In 1860 J. E. Lenoir invented and then built the first internal combustion engine “firing inflammable air with a due portion of common air under a piston” as Cayley had proposed in 1809.

It is true that, as soon as illuminating gas was invented by Philippe Lebon in 1799, means were sought to use gas as a fuel for machines that produced power, with the principal difficulty being thought to lie in the means of mixing gas and air before combustion could take place. Lenoir solved the problem in one masterful stroke by effecting the mixing inside the working cylinder itself. He simply built a copy of a steam engine that admitted a quantity of gas and air during the first part of the working stroke which was then ignited half-way, producing an explosion that did useful work during the rest of the stroke. The return stroke was used to expel the burned gases and then the cycle began anew.

Lenoir’s engine generated much enthusiasm among aircraft pioneers, but this enthusiasm soon waned when it was found that the heavy, shaking gas motor, needing water to cool the cylinder and consuming great amounts of gas and lubricating oil, was less suitable as an aeronautical powerplant than the steam engine in use at that time.

However, several other initiatives began to encourage the aeronautical movement both in England and in France. After the demise of Dupuis Delcourt’s society in 1853, a group of enthusiasts gathered in Paris on 30 July 1863 at the instigation of the well-known photographer Jules Nadar to hear a manifesto concerning aerial locomotion which caused considerable agitation.

Читать дальше