In the spring of 1896 Pilcher built his third glider, the “Gull”. In a bold move, the wing area was enlarged to 300 sq ft and the weight was kept to a low 55 lbs, but Pilcher had gone too far in lowering the wing loading and the “Gull” was nearly unmanageable in any kind of wind.

The “Gull” did not last long either and was replaced by a smaller version of it, named the “Hawk”, which became Pilcher’s most successful machine. The wing area was reduced to 180 sq ft and it weighed 50 lbs. The need for inherent stability was kept firmly in mind and when Lilienthal crashed to his death in August 1896, Pilcher, who had heard about the redesigned movable tail, offered what was probably the correct diagnosis of Lilienthal’s accident, which was probably due to the abandonment of inherent stability in favour of positive control.

The “Hawk” was such a success that Pilcher again began to look around for an engine capable of overcoming the force of gravity, the glider’s source of power. “The object of experimenting with soaring machines” wrote Pilcher at that time, “is to enable one to have practice in starting and alighting and controlling a machine in the air. They cannot possibly float horizontally in the air for any length, of time, but to keep going must necessarily lose in elevation. They are excellent schooling machines and that is all they are meant to be, until power, in the shape of an engine working a screw propeller... is added.”

Pilcher, at that time heard rumours of an engine in the US which gave 1 hp for a weight of 15 lbs, but which never materialized. So, like most of the pioneers of that decade, Pilcher decided that he would have to build an engine himself. He designed a two-cylinder horizontally-opposed engine which he calculated to give 4 hp for a weight of 44 lbs and, after achieving some very good flights, especially one in June 1897 during which he covered 750 ft under perfect balance, he started to build a powered aeroplane.

In 1897 Pilcher had formed a company in partnership with W. G. Wilson, and in November had begun corresponding with Chanute. In January 1898, whilst he was working on his engine, he wrote to Chanute that he intended to make “a machine like one of your multiple sail ones”. Chanute replied that Pilcher was welcome to make a multiple-wing machine, but he ruled the biplane out because Chanute did not wish to incur Herring’s wrath.

Pilcher thereupon designed a project for a quadruplane, but finally decided on a triplane, as favoured by Chanute, including the stabilizing tail at the rear which was fixed according to Lilienthal’s directions. But before he could finish his engine so as to have the triplane ready for tests in flight, Pilcher’s fate overtook him.

In the midst of a drive for raising funds to help defray the cost for the powered machine, Pilcher decided to make a demonstration flight in the “Hawk” in the presence of a select group of visitors, among whom were Major B. F. S. Baden Powell, secretary of the Aeronautical Society and later its president, who had come down from London for that purpose.

On 30 September 1899 the visitors were present and Pilcher was anxious not to disappoint them and, although the weather was unfavourable with gusty winds and light showers, he decided to go ahead. His take-off system at that time consisted in having his plane towed by means of a tackle that multiplied the speed of the two horses that drew it. A first attempt was successful but the line broke. On the second attempt one of the guy wires holding the tail in position broke and the “Hawk” dived down out of control and crashed.

Pilcher died two days later of the injuries he had sustained, the second victim of heavier-than-air machine experiments and the first victim of structural failure during flight. He was also the first of several airmen who suffered accidents which resulted from risk taken in adverse circumstances so as not to disappoint spectators who had come to witness a flight.

Stability versus Control

Most of the aviation pioneers of the nineteenth century were handicapped by their inability to differentiate unequivocally between stability and control. Again it was Sir George Cayley who put the problems in their proper perspective. He argued that the first requisite for a flying machine was lift; the second was stability in the air, and once these qualities were assured then control had to be added.

Pénaud’s model aeroplanes were inherently stable, but he later incorporated methods of control in the specifications of his patent. On the other hand, the bird and its admirable way of flying had given too many people the idea that it would be easy to manage an aeroplane in flight by a multitude of controlling devices, while disregarding stability altogether.

In Lilienthal’s case it is easy to see why he abandoned the inherent stability of his most efficient gliders, those which he used from 1892 to 1894. It was because he wanted to achieve longer flights, which in turn demanded larger wings, and as he also wanted to fly in stronger winds, this required better control and, added to that, he also wanted to incorporate a motor. All these factors made for larger and heavier aeroplanes, but the steering of these by means of movements of the body was becoming increasingly hard with every pound of weight that was added.

The idea of introducing movable auxiliary surfaces for better control was correct, but the relinquishment of inherent stability was not. It would take ten more years before the aircraft designers became conscious of the fact that controls had to be superimposed on an inherently stable construction and that to abandon stability in order to obtain better control was a grave mistake.

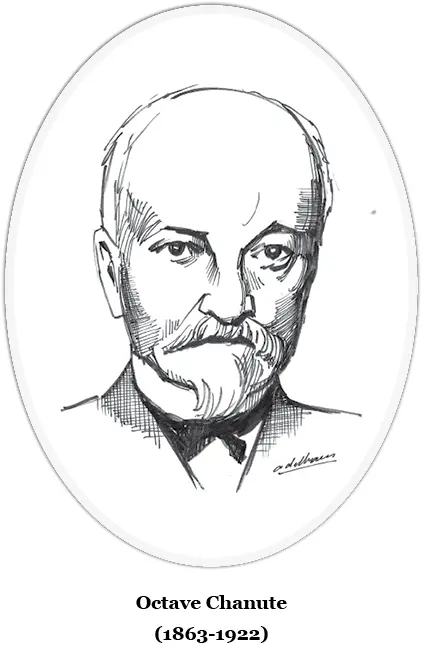

Octave Chanute (1890/1894)

Ader, Maxim and Lilienthal were not very interested in each other’s experiments. Maxim called Lilienthal a parachutist and Lilienthal countered by referring to Maxim’s costly trials as “how not to do it”.

But in the United States a man who was keenly interested in all aeronautical pioneers was becoming active and was preparing to devote the last years of his life exclusively to the promotion of human flight. By so doing he came into contact with most of those who were involved in aviation during the eventful last decade of the nineteenth century. This man was Octave Chanute.

His interests soon turned him into an indefatigable letter-writer. One of the first letters he wrote when he returned from his trip to Paris was to Mouillard, along with a copy of the paper Chanute had delivered at the International Aeronautical Conference of 1889.

Mouillard replied on 16 April 1890, thanking Chanute for his pamphlet but commenting on his “deplorable habit of paying little attention to writings pertaining to pure mathematics” and indicated that he was proceeding instinctively and was being moved by his tremendous enthusiasm. He ended his letter with “enthusiastic greetings”, after referring to his “professors” in the following terms: “In case some theoretical problems are confronting you in your experiments I would like to put my professors at your disposal; they are neighbours of mine, two vultures, which are brilliant demonstrators.”

It was clear that Mouillard remained completely devoted to the intricacies and wonders of bird flight and his enthusiasm was soon shared keenly Chanute, who became as convinced of the necessity of imitating the “instinct of the bird” as Mouillard.

Now that Mouillard had found a kindred spirit there was no stopping him, and on 20 November 1890, in another long letter to Chanute, he explained how a bird warped the tip of its wing in order to arrest its movement through the air on that side, thereby inducing a powerful turning movement. Mouillard explained that he had reproduced this movement several times and that the displacement of the body (just as Lilienthal was able to do a few years later) or the diminishing of the wing surface was far less effective than the warping of the wing tips which he called a “brutal means of steering”.

Читать дальше