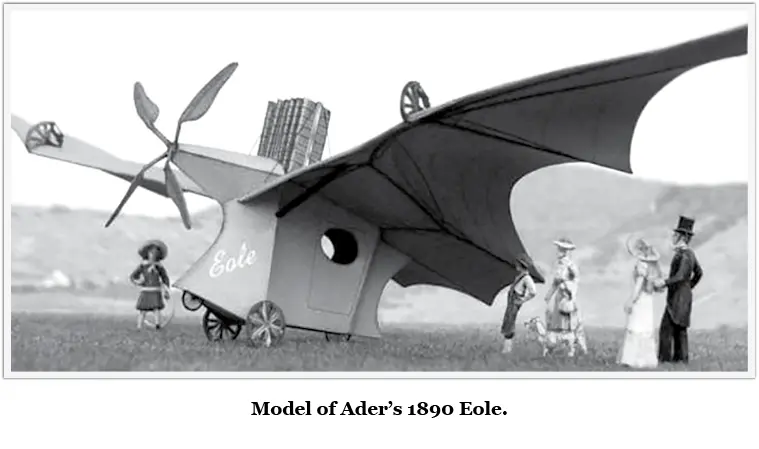

After the uproar in the press during the summer of 1891, Ader showed the “Eole” in a pavilion belonging to the city of Paris where it was inspected by the Minister of War, Charles de Freycinet; though it is strange that no photograph of the aeroplane was taken on that occasion.

De Freycinet was interested and Ader was allowed to move his aircraft to the military camp of Satory for further tests and for evaluation as to its possible military usefulness. Ader also claimed to have flown the “Eole” at the Satory camp, but very soon after its arrival in September 1891, it deviated from its course during one of the test runs and struck a pile of material that had served to prepare the test area and when the officer despatched to inspect Ader’s “Eole” arrived, he found nothing but a wreck.

Having spent much of his fortune on aeronautical experiments, Ader could have become dispirited but he seems to have possessed that indestructible faith in his own vision that marks so many outstanding personalities.

He was able to convince the officials of the War Ministry and on 3 February 1892 a contract was signed with the French State which accorded Ader a payment of 300,000 francs ($60,000) for the construction of a new aeroplane. He was also promised the return, by an act of Parliament, of the 600,000 Frs he had already spent, plus an additional sum of a million francs in return for the relinquishment by Ader and his heirs of all rights over his invention.

This contract sounds highly irrational because Ader bound himself by its terms to build an aeroplane able to carry a pilot and a passenger or the equivalent weight (75 kg) in explosives, as well as enough fuel and water for a flight of six hours at 34 mph with the ability to reach an altitude of 1,000 ft. These were daunting requirements for a man who had just built a machine that was barely able (if at all) to lift itself over a few feet with just the inventor on board. Ader must have been either a determined optimist or desperate for money.

Once the contract was signed, Ader started work on a second single-engined aeroplane but meanwhile he calculated that in order to comply with the clauses of the contract he would have to build a bigger aeroplane carrying two engines, each driving a propeller.

The authorities in charge agreed with his new proposals and in July 1894 an additional sum of 250,000 Frs ($50,000) was granted. These two large sums did not come from government funds but were part of a legacy made by Giffard to the French State, perhaps with the proviso that a part or the whole of the legacy was to be expended on the construction of an aerial machine.

It should be recalled here that Ader received the money that Pénaud had hoped to obtain for furthering his own experiments and when this hope was thwarted it led to Pénaud’s suicide, followed by that of Giffard.

The “Avion III”, as the new aeroplane was to be called, closely followed the pattern of the “Eole” in that it was another tailless bat-winged machine but it was bigger, having a wing surface of 430 sq ft at their maximum extension and when finished it weighed about 400 kg (880 lbs). Its two steam engines produced a total output of at least 40 hp (some sources claim 60 hp) so that, with a wing loading of 2 lbs/sq ft and a power loading of less than 20 lbs per hp it was a great advance over the already extraordinary specifications of the “Eole”, and Ader may well have believed that he would be able to comply with the clauses of the contract.

A big building lot was acquired and a complete aeronautical factory was built. Twenty-three men were engaged and work progressed during four years, the first time that so much money had been spent on an aeroplane.

The construction probably took more time than had originally been estimated but in 1897 the “Avion III” was ready to Ader’s satisfaction. The extremely light steam engines functioned and the wings were submitted to a static loading test corresponding to the weight of the machine. When Ader informed the War Ministry of the completion of the aeroplane a committee was appointed, consisting of three generals and three learned professors, all with excellent credentials and headed by General Mensier as president of the committee.

After inspection at the workshops, the “Avion” was moved to the manoeuvring grounds of Satory where, under the supervision of Lieuteneant Binet, a testing ground was prepared, consisting of a circular area 120 ft wide and with a diameter of 1,500 ft.

The expediency of selecting a circular testing ground may be questioned but Ader probably wanted to test his aeroplane on calm days and a ring form takes less space than a square or rectangular area.

A first test was held on the 12th October in the presence of General Mensier. Ader had to wait until sunset for the wind to drop and he started on his first trial run at 5.25 pm. With the machine running at around 12 mph, Ader, by means of a steerable rear wheel, was able to follow the chalk line which ran down the middle of the circular track and, having made a complete circuit, he stopped at his point of departure.

This was considered a success, so a trial flight was arranged for two days later, on 14 October. This time General Mensier was accompanied by General Grillion, another member of the Committee, with Lieutenant Binet, who had been in charge of the preparation of the testing ground, was also present. According to the official report drawn up on 21 October by General Mensier, there was a fairly strong and gusty wind blowing from the south.

It is to be wondered why Ader, after all the time and money spent on this project, did not insist on waiting for a calm day, as the report states that Ader had explained the danger of gusts of wind to the generals. Anyway, towards sunset the wind appeared to die down and it is possible that the generals did not want to postpone the trial for another day.

But the wind had not died down completely, and Ader, starting at 5.15 pm had the wind from the rear. When his machine had completed a quarter of the circular area and was running at a brisk pace, a gust of wind caught it from the side and the “Avion III” suddenly swerved away from the track, struck the ground with a wing and came to a stop, much damaged. On seeing his machine leave the track, Ader shut off the steam immediately, which was the best thing he could have done. In his official report General Mensier explicitly stated that at no point of its run did the “Avion” become airborne, although the rear wheel may have left the ground over a short distance. Lt Binet later confirmed this to the eminent engineer Armengaud, “he did not leave the ground or at the most lifted a few centimetres”.

The official report ended with the recommendation that the trials be continued the following spring, but nothing came of it and Ader’s aeronautical experiments were over. But, as sometimes happens, that event was to have a sequel that has had consequences up to the present day.

After Santos-Dumont made the first officially recorded flight in 1906, Ader came forward with the claim that on 14 October 1897 he had made a flight of 300 metres. On the basis of the sketch he presented, Ader would have taken off and flown with a ¾ rear wind. Ader, who had himself observed in 1882 that no bird ever takes off with a wind from the rear or from the side, should have known better than to make such an absurd claim, but sour grapes or the inability to continue enduring the great financial and moral loss he had suffered, made him do it. But because the making of a “first flight” acquired a bigger aura in the eyes of the general public than the construction of the first correctly designed aeroplane, Ader’s claim is still taken seriously and is considered an important historical milestone, which in a way it is.

Читать дальше