Meanwhile, however, Japanese aspirations received a check from which they were to take several years to recover. The statesmen of the Mikado were even unable to obtain a pledge from China that the territories yielded back to her by Japan would never be alienated to a third Power. Russia's delicate sense of honor, it appeared, revolted against the imputation implied, and therefore China must give no pledge. On the other hand, Russia would be so generous as to give an assurance on her own account that she had no designs upon Manchuria. Forced to content herself with the cold comfort of this empty and meaningless declaration, and baffled upon all essential points, Japan sullenly withdrew her troops from the mainland and settled down to nurse her just wrath, and prepare for the inevitable day of reckoning.

JAPANESE INFANTRY ATTACKING A CHINESE POSITION.

The centre of interest was now shifted to Peking, where began that amazing scramble among the European Powers for commercial, and especially for railway, concessions in China, which, by unmasking the ambitions of some countries, and revealing the community of interests of others, has led ultimately to important modifications of international policy, and to a re-arrangement of alliances. The complexity of the game, the swiftness of the moves, and the ignorance of the average man, not only of the issues involved, but even of the main geographical and economic features of the immense country which was the object of the struggle—all contrived to puzzle the mind and to darken the understanding; but a vague feeling, only too clearly justified by the events, arose in this country that England and America were not getting the best of the conflict, and that Russia and Germany were making all the running. In truth, there is no doubt that the skill, or perhaps, to speak more correctly, the duplicity, of the Russian diplomatists both in Peking and in St. Petersburg left their competitors completely behind. Foremost among them there emerges at this time the sinister figure of M. Pavloff, the Minister of the Czar at the Chinese Court. The tortuous diplomacy of the Muscovite has produced no more characteristic tool. M. Pavloff has been the stormy petrel of the Far East. Intrepid, resourceful to a degree, unscrupulous beyond the average, he is ever in the forefront of the diplomatic battle line. His appearance in any part of the field is the signal for new combinations, fresh aggressions, the stirring up of bad blood between nations, and the unsettlement of apparently settled questions. A man whose god is the Czar; a man with whom the expansion of the Empire of the Little White Father is an ideal cherished with almost religious fervor; a man who indeed in all probability honestly regards the extension of the Russian autocracy over the world as essential to the due progress of higher civilization—he is thoroughly typical of the class of agents whose devoted services Russia has always managed to secure for the spread of her Empire and the gradual but steady absorption of fresh territory all over Asia, whether in China, Persia, Turkestan or Tibet.

Such was the instrument possessed by the Government of the Czar at the Court of Peking, and he was not likely to neglect the unique opportunity which lay ready to his hand. By her action in restoring Port Arthur to the nerveless grasp of China, Russia naturally assumed the character of a powerful friend whose smile was to be courted and whose frown was to be proportionately dreaded. What more natural, in the circumstances, than that the Emperor should grant to the subjects of his brother and ally, the Czar, peculiar commercial privileges in the country which had been so generously rescued from the grip of Japan and restored to the Empire of the King of Heaven?

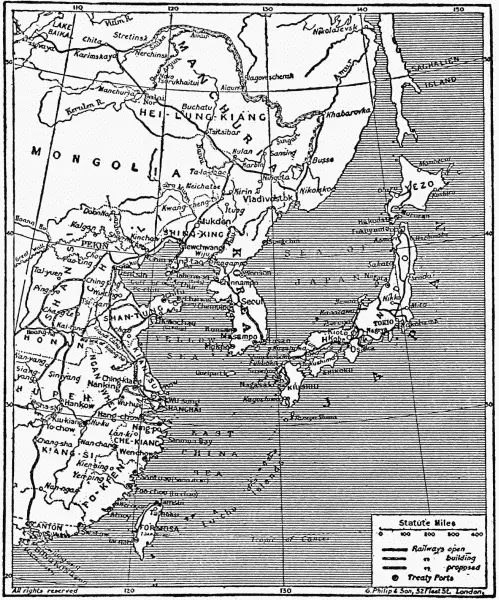

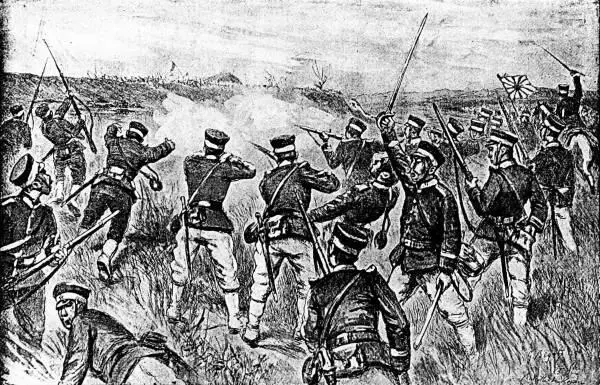

The first result of M. Pavloff's policy of disinterested friendship became manifest in 1896, when the Chinese Government concluded an agreement with the Russo-Chinese Bank, providing for the formation of a company to be styled the Eastern Chinese Railway Company, the ownership of which was to be vested solely in Russian and Chinese subjects and which was to construct and work a railway within the confines of China, from one of the points on the western borders of the province of Heh-Lung-Kiang to one of the points on the eastern borders of the province of Kirin; and to the connection of this railway with those branches which the Imperial Russian Government would construct to the Chinese frontier from Trans-Baikalia and the Southern Ussuri lines. The institution, which went by the plain, solid, commercial name of the Russo-Chinese Bank, was, of course, merely a sort of Far Eastern annex of the Finance Bureau of M. de Witte, and the line thus modestly announced was the nucleus of the great railway which has since played such a large part in consolidating the Russian dominion over Manchuria. At the outset it was pretended that the line was to be merely a short cut to Vladivostock, but the true ambitions at the bottom of the scheme became apparent when Russian engineers began to pour into the country followed by squadrons of Cossacks, nominally for the protection of the new railway, but really in pursuance of Russia's invariable policy of impressing the natives with a due sense of her enormous military strength.

MAP OF THE AREA AFFECTED BY THE WAR.

The construction of the line, however, had not proceeded very far when, in 1897, an event occurred which gave the Czar's Government the chance for which they had long been anxiously looking. The massacre of some German missionaries led to swift and stern reprisals on the part of the Kaiser. The port of Kiao-Chau, in the province of Shantung, was seized until reparation was made for the outrage committed upon the majesty of the German Empire, and to placate the offended "mailed fist," the feeble Government of China were compelled to hand over this important position to Germany as a permanent possession, although, by a characteristic euphemism of diplomacy, the transaction was conveniently styled a "lease." Russia's opportunity was now too good to be neglected. Emboldened by the example of Germany, she demanded—for that is what her so-called "request" amounted to in reality—permission from the Chinese Government to winter her fleet at Port Arthur. Perhaps it may be imputed to her for righteousness that, unscrupulous as she is, she has never found it necessary to employ the missionaries of Christ as instruments of aggression; at all events on this occasion she had no such excuse at hand. The helpless Chinese assented, of course, to her request; but now Great Britain, awake at last to the dangers which threatened her Treaty rights, endeavored to intervene. Strong representations were made by the English Minister to the Tsung-lai-yamen as to the necessity for turning the port of Ta-lien-wan—which lies immediately adjacent to Port Arthur—into a Treaty port; that is to say, throwing it open to the trade of the world on the same terms as obtain at Shanghai, Canton, Hankau, and other ports of China at which the policy of the Open Door prevails.

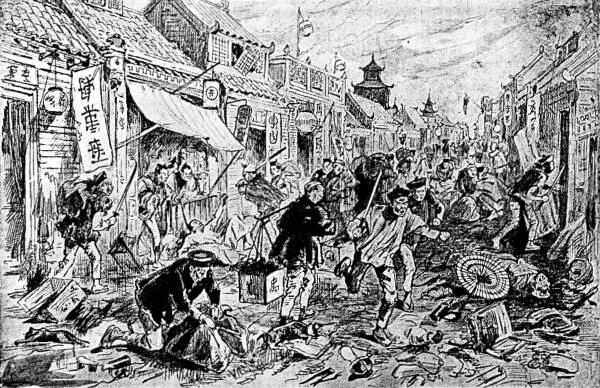

THE JAPANESE AT PORT ARTHUR.

English statesmen, however, were no match for the wily Russians, who had the ear of the Chinese mandarins. The Government of the Czar successfully opposed the suggestion, and backed up its representations at Peking by significant display of force, for a considerable fleet of men-of-war arrived at Port Arthur and Ta-lien-wan in the spring of 1898 and practically took possession. Then, by a mingled process of terrorism and corruption, the Chinese Government were induced to grant the Czar a "lease" of the two harbors on the same terms as those on which Germany had been granted possession of Kiao-Chau, and, equally important, to permit the extension of the line of the Eastern Chinese Railway Company to Port Arthur. Thus came into being the Manchurian Railway, the construction of which was pushed on with feverish activity.

Читать дальше