It must not be thought, however, that every governor got off as easily as Franklin's tale implies. On the contrary, the legislatures, like Cæsar, fed upon meat that made them great and steadily encroached upon executive prerogatives as they tried out and found their strength. If we may believe contemporary laments, the power of the crown in America was diminishing when it was struck down altogether. In New York, the friends of the governor complained in 1747 that "the inhabitants of plantations are generally educated in republican principles; upon republican principles all is conducted. Little more than a shadow of royal authority remains in the Northern colonies." "Here," echoed the governor of South Carolina, the following year, "levelling principles prevail; the frame of the civil government is unhinged; a governor, if he would be idolized, must betray his trust; the people have got their whole administration in their hands; the election of the members of the assembly is by ballot; not civil posts only, but all ecclesiastical preferments, are in the disposal or election of the people."

Though baffled by the "levelling principles" of the colonial assemblies, the governors did not give up the case as hopeless. Instead they evolved a system of policy and action which they thought could bring the obstinate provincials to terms. That system, traceable in their letters to the government in London, consisted of three parts: (1) the royal officers in the colonies were to be made independent of the legislatures by taxes imposed by acts of Parliament; (2) a British standing army was to be maintained in America; (3) the remaining colonial charters were to be revoked and government by direct royal authority was to be enlarged.

Such a system seemed plausible enough to King George III and to many ministers of the crown in London. With governors, courts, and an army independent of the colonists, they imagined it would be easy to carry out both royal orders and acts of Parliament. This reasoning seemed both practical and logical. Nor was it founded on theory, for it came fresh from the governors themselves. It was wanting in one respect only. It failed to take account of the fact that the American people were growing strong in the practice of self-government and could dispense with the tutelage of the British ministry, no matter how excellent it might be or how benevolent its intentions.

CHAPTER IV

THE DEVELOPMENT OF COLONIAL NATIONALISM

Table of Contents

It is one of the well-known facts of history that a people loosely united by domestic ties of a political and economic nature, even a people torn by domestic strife, may be welded into a solid and compact body by an attack from a foreign power. The imperative call to common defense, the habit of sharing common burdens, the fusing force of common service—these things, induced by the necessity of resisting outside interference, act as an amalgam drawing together all elements, except, perhaps, the most discordant. The presence of the enemy allays the most virulent of quarrels, temporarily at least. "Politics," runs an old saying, "stops at the water's edge."

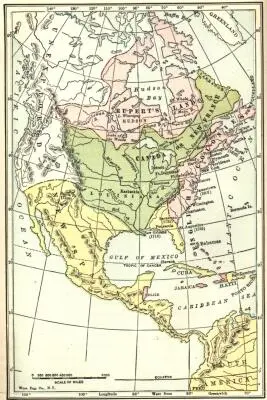

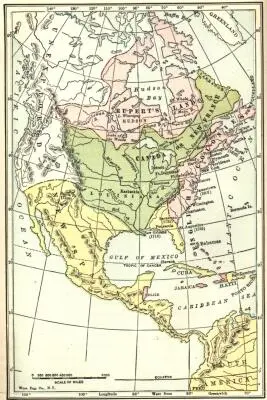

This ancient political principle, so well understood in diplomatic circles, applied nearly as well to the original thirteen American colonies as to the countries of Europe. The necessity for common defense, if not equally great, was certainly always pressing. Though it has long been the practice to speak of the early settlements as founded in "a wilderness," this was not actually the case. From the earliest days of Jamestown on through the years, the American people were confronted by dangers from without. All about their tiny settlements were Indians, growing more and more hostile as the frontier advanced and as sharp conflicts over land aroused angry passions. To the south and west was the power of Spain, humiliated, it is true, by the disaster to the Armada, but still presenting an imposing front to the British empire. To the north and west were the French, ambitious, energetic, imperial in temper, and prepared to contest on land and water the advance of British dominion in America.

Relations with the Indians and the French

Indian Affairs.—It is difficult to make general statements about the relations of the colonists to the Indians. The problem was presented in different shape in different sections of America. It was not handled according to any coherent or uniform plan by the British government, which alone could speak for all the provinces at the same time. Neither did the proprietors and the governors who succeeded one another, in an irregular train, have the consistent policy or the matured experience necessary for dealing wisely with Indian matters. As the difficulties arose mainly on the frontiers, where the restless and pushing pioneers were making their way with gun and ax, nearly everything that happened was the result of chance rather than of calculation. A personal quarrel between traders and an Indian, a jug of whisky, a keg of gunpowder, the exchange of guns for furs, personal treachery, or a flash of bad temper often set in motion destructive forces of the most terrible character.

On one side of the ledger may be set innumerable generous records—of Squanto and Samoset teaching the Pilgrims the ways of the wilds; of Roger Williams buying his lands from the friendly natives; or of William Penn treating with them on his arrival in America. On the other side of the ledger must be recorded many a cruel and bloody conflict as the frontier rolled westward with deadly precision. The Pequots on the Connecticut border, sensing their doom, fell upon the tiny settlements with awful fury in 1637 only to meet with equally terrible punishment. A generation later, King Philip, son of Massasoit, the friend of the Pilgrims, called his tribesmen to a war of extermination which brought the strength of all New England to the field and ended in his own destruction. In New York, the relations with the Indians, especially with the Algonquins and the Mohawks, were marked by periodic and desperate wars. Virginia and her Southern neighbors suffered as did New England. In 1622 Opecacano, a brother of Powhatan, the friend of the Jamestown settlers, launched a general massacre; and in 1644 he attempted a war of extermination. In 1675 the whole frontier was ablaze. Nathaniel Bacon vainly attempted to stir the colonial governor to put up an adequate defense and, failing in that plea, himself headed a revolt and a successful expedition against the Indians. As the Virginia outposts advanced into the Kentucky country, the strife with the natives was transferred to that "dark and bloody ground"; while to the southeast, a desperate struggle with the Tuscaroras called forth the combined forces of the two Carolinas and Virginia.

From an old print Virginians Defending Themselves against the Indians

From such horrors New Jersey and Delaware were saved on account of their geographical location. Pennsylvania, consistently following a policy of conciliation, was likewise spared until her western vanguard came into full conflict with the allied French and Indians. Georgia, by clever negotiations and treaties of alliance, managed to keep on fair terms with her belligerent Cherokees and Creeks. But neither diplomacy nor generosity could stay the inevitable conflict as the frontier advanced, especially after the French soldiers enlisted the Indians in their imperial enterprises. It was then that desultory fighting became general warfare.

Читать дальше