This time she held it on with a firm pressure that I was too weak to resist. I expostulated feebly that I was drowning, which she also laid to my mental exaltation, and then I finally dropped into a damp sleep. It was probably midnight when I roused again. I had been dreaming of the wreck, and it was inexpressibly comforting to feel the stability of my bed, and to realize the equal stability of Mrs. Klopton, who sat, fully attired, by the night light, reading Science and Health .

"Does that book say anything about opening the windows on a hot night?" I suggested, when I had got my bearings.

She put it down immediately and came over to me. If there is one time when Mrs. Klopton is chastened—and it is the only time—it is when she reads Science and Health . "I don't like to open the shutters, Mr. Lawrence," she explained. "Not since the night you went away."

But, pressed further, she refused to explain. "The doctor said you were not to be excited," she persisted. "Here's your beef tea."

"Not a drop until you tell me," I said firmly. "Besides, you know very well there's nothing the matter with me. This arm of mine is only a false belief." I sat up gingerly. "Now—why don't you open that window?"

Mrs. Klopton succumbed. "Because there are queer goings-on in that house next door," she said. "If you will take the beef tea, Mr. Lawrence, I will tell you."

The queer goings-on, however, proved to be slightly disappointing. It seemed that after I left on Friday night, a light was seen flitting fitfully through the empty house next door. Euphemia had seen it first and called Mrs. Klopton. Together they had watched it breathlessly until it disappeared on the lower floor.

"You should have been a writer of ghost stories," I said, giving my pillows a thump. "And so it was fitting fitfully!"

"That's what it was doing," she reiterated. "Fitting flitfully—I mean flitting fitfully—how you do throw one out, Mr. Lawrence! And what's more, it came again!"

"Oh, come now, Mrs. Klopton," I objected, "ghosts are like lightning; they never strike twice in the same night. That is only worth half a cup of beef tea."

"You may ask Euphemia," she retorted with dignity. "Not more than an hour after, there was a light there again. We saw it through the chinks of the shutters. Only— this time it began at the lower floor and climbed! "

"You oughtn't to tell ghost stories at night," came McKnight's voice from the doorway. "Really, Mrs. Klopton, I'm amazed at you. You old duffer! I've got you to thank for the worst day of my life."

Mrs. Klopton gulped. Then realizing that the "old duffer" was meant for me, she took her empty cup and went out muttering.

"The Pirate's crazy about me, isn't she?" McKnight said to the closing door. Then he swung around and held out his hand.

"By Jove," he said, "I've been laying you out all day, lilies on the door-bell, black gloves, everything. If you had had the sense of a mosquito in a snow-storm, you would have telephoned me."

"I never even thought of it." I was filled with remorse. "Upon my word, Rich, I hadn't an idea beyond getting away from that place. If you had seen what I saw—"

McKnight stopped me. "Seen it! Why, you lunatic, I've been digging for you all day in the ruins! I've lunched and dined on horrors. Give me something to rinse them down, Lollie."

He had fished the key of the cellarette from its hiding-place in my shoe bag and was mixing himself what he called a Bernard Shaw—a foundation of brandy and soda, with a little of everything else in sight to give it snap. Now that I saw him clearly, he looked weary and grimy. I hated to tell him what I knew he was waiting to hear, but there was no use wading in by inches. I ducked and got it over.

"The notes are gone, Rich," I said, as quietly as I could. In spite of himself his face fell.

"I—of course I expected it," he said. "But—Mrs. Klopton said over the telephone that you had brought home a grip and I hoped—well, Lord knows we ought not to complain. You're here, damaged, but here." He lifted his glass. "Happy days, old man!"

"If you will give me that black bottle and a teaspoon, I'll drink that in arnica, or whatever the stuff is; Rich,—the notes were gone before the wreck!"

He wheeled and stared at me, the bottle in his hand. "Lost, strayed or stolen?" he queried with forced lightness.

"Stolen, although I believe the theft was incidental to something else."

Mrs. Klopton came in at that moment, with an egg-nog in her hand. She glanced at the clock, and, without addressing any one in particular, she intimated that it was time for self-respecting folks to be at home in bed. McKnight, who could never resist a fling at her back, spoke to me in a stage whisper.

"Is she talking still? or again?" he asked, just before the door closed. There was a second's indecision with the knob, then, judging discretion the better part, Mrs. Klopton went away.

"Now, then," McKnight said, settling himself in a chair beside the bed, "spit it out. Not the wreck—I know all I want about that. But the theft. I can tell you beforehand that it was a woman."

I had crawled painfully out of bed, and was in the act of pouring the egg-nog down the pipe of the washstand. I paused, with the glass in the air.

"A woman!" I repeated, startled. "What makes you think that?"

"You don't know the first principles of a good detective yarn," he said scornfully. "Of course, it was the woman in the empty house next door. You said it was brass pipes, you will remember. Well—on with the dance: let joy be unconfined."

So—I told the story; I had told it so many times that day that I did it automatically. And I told about the girl with the bronze hair, and my suspicions. But I did not mention Alison West. McKnight listened to the end without interruption. When I had finished he drew a long breath.

"Well!" he said. "That's something of a mess, isn't it? If you can only prove your mild and childlike disposition, they couldn't hold you for the murder—which is a regular ten-twent-thirt crime, anyhow. But the notes—that's different. They are not burned, anyhow. Your man wasn't on the train—therefore, he wasn't in the wreck. If he didn't know what he was taking, as you seem to think, he probably reads the papers, and unless he is a fathead, he's awake by this time to what he's got. He'll try to sell them to Bronson, probably."

"Or to us," I put in.

We said nothing for a few minutes. McKnight smoked a cigarette and stared at a photograph of Candida over the mantel. Candida is the best pony for a heavy mount in seven states.

"I didn't go to Richmond," he observed finally. The remark followed my own thoughts so closely that I started. "Miss West is not home yet from Seal Harbor."

Receiving no response, he lapsed again into thoughtful silence. Mrs. Klopton came in just as the clock struck one, and made preparation for the night by putting a large gaudy comfortable into an arm-chair in the dressing-room, with a smaller, stiff-backed chair for her feet. She was wonderfully attired in a dressing-gown that was reminiscent, in parts, of all the ones she had given me for a half dozen Christmases, and she had a purple veil wrapped around her head, to hide Heaven knows what deficiency. She examined the empty egg-nog glass, inquired what the evening paper had said about the weather, and then stalked into the dressing-room, and prepared, with much ostentatious creaking, to sit up all night.

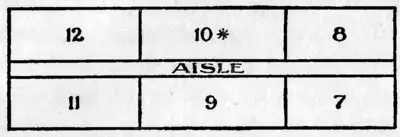

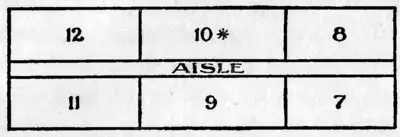

We fell silent again, while McKnight traced a rough outline of the berths on the white table-cover, and puzzled it out slowly. It was some thing like this:

"You think he changed the tags on seven and nine, so that when you went back to bed you thought you were crawling into nine, when it was really seven, eh?"

Читать дальше