Keywords:Lip anatomy, lip biophysical properties, lip surface properties, long-wear lipstick, in vitro evaluation, consumer sensory testing

Lipsticks have been an integral part of cosmetics since the dawn of civilization. The first man-made lipstick, which consisted of black kohl, was made famous during the ancient Egyptian period as part of Cleopatra’s makeup routine. Lipsticks went through a period of low popularity during the European Middle Ages, but returned to glory during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. During the Second World War, the use of lipsticks had not only made women feel more feminine, but rather red lipstick was seen as a symbol of patriotism and defiance of difficult times during the war. The basis of modern lipstick was invented by chemist Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi during the Islamic Golden Age and became a product of commercialization in late 19 thcentury, thanks to industrial advancements. Given the long history of lipstick, consumers have developed clear expectations in regards to performance, appearance, and use experience [1]. The obvious immediate requirement is that the lipsticks should contain no toxic components and irritants. Exposure to potential irritants from lipstick is mainly by swallowing, such as after a consumer licks their lips. Currently, color additives must have FDA approval for its intended use, as many can contain traces of lead as an impurity. Following an investigation effort in 2007, the FDA determined that up to 10 parts per million (ppm) of lead in lipsticks would not pose a health risk.

The long-wear lipstick market can be classified into four key categories, each of which has its own benefits and appeals to consumers: long-wear, gloss, lasting lip gloss, and lip care. Long-wear lipstick, which was also advertised as transfer-resistant, was introduced in the cosmetics market by Shiseido in 1986 as a solution to problems associated with wear and movement experienced by a majority of lipstick users [2]. Functionally, lipsticks are expected to bring instant gratification in regards to the user’s appearance, regardless of style and color. To accomplish this, an ideal lipstick is expected to be non-drying, provide sun protection, and have great wear, color, and shine. Wear of lipsticks shall be mentioned further throughout the chapter and can hereby be formally defined as the user’s experience as a whole, consumer perception of performance and comfort, and formulation lastingness. Lipsticks should also be easy to apply on the lips and leave a thin film deposit. Early iterations of lipstick technology did not withstand the challenges associated with consumer use and wear, which, in turn, left the consumers desiring a formulation that was able to weather their lifestyle without reduced performance or need for re-application. As a result, long-wear lipstick, substantiating claims of non-transfer, lasting color, and no smearing/smudging, was introduced to the public in the form of a two-part kit. In this kit, the first layer, a pigmented lipstick, was intended to deposit color on the lips and was to be covered by a secondary overcoat containing film-forming polymers [3]. It is important to note the key difference between lipsticks described as long-wear versus transfer-resistant. Long-wear lipstick refers to the coloring remaining the same or visually consistent from the time of application over a period of time [4]. Transfer-resistance relates to the ability of the product not to be transferred onto a secondary surface upon contact. This would relate to the formulation being removed from the consumer’s lips after touching another surface, such as a glass. However, most of the time these terms are used interchangeably with consumers.

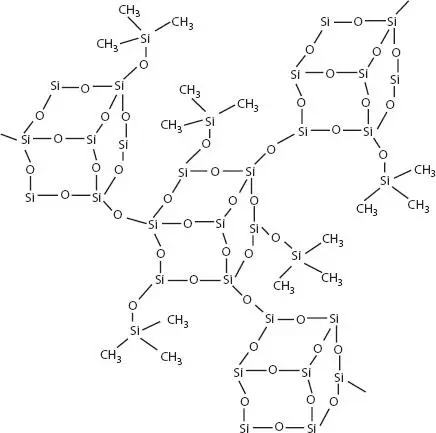

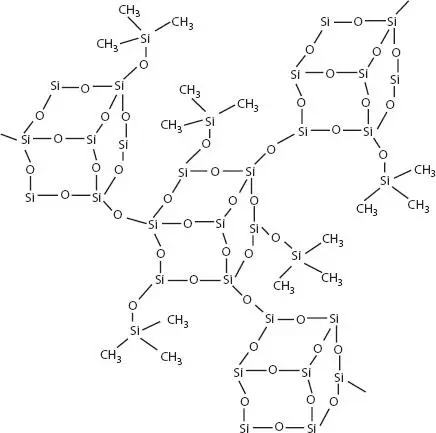

A key challenge in lipstick development is attaining an acceptable adhesion to the skin and semi-mucous areas around the lip region. After application, products can tend to migrate into cracks in the lip due to poor adhesion, creating an uneven coating and coloring over time [5]. Efforts to alleviate this problem resulted in the use of a pressure-sensitive silicone resin with MQ units (trimethyl endcap and four-way branch point units). This MQ resin, as seen in Figure 1.1, is commonly used to boost lip adherence, but the material itself is brittle, thus requiring a plasticizer in order to allow for film formation [2, 3]. This plasticizer contributes to the formation of a pliable film. Interactions with other components of the formulation, such as pigments, solvents, and fillers, also enhance product adhesion to the skin [2]. Most long-wear cosmetics utilize MQ resin technology because its surface free energy is similar to that of the human skin [2]. Skin surface free energy is a key factor for a cosmetic’s wettability, adsorption, and adhesion [6]. This key characteristic is also what permits the technology to allow for better wear and adhesion to the consumer’s lips. In formulations of products like Revlon ColorStay and CoverGirl, the MQ resin is used in conjunction with poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) gum to enhance the tack of the final product [2]. Additionally, initial versions of these non-transfer technologies utilized a volatile solvent with low viscosity PDMS or high viscosity gum in order to deposit a non-transferrable film upon solvent evaporation [2]. L’Oreal further developed the non-transfer MQ resin technology by introducing the use of a thermoplastic elastomer as a replacement for the PDMS gum and oil, in turn enhancing the product durability and adhesion to the lip [2]. This was incorporated into Maybelline Superstay 24 and L’Oreal Infallible lipsticks, permitting a wider range of motion of the lips and longer contact with a secondary surface, such as a drinking glass, without sacrificing the durability and appearance of the formulation [2].

Figure 1.1 Structure of the MQ resin used to enhance formulation adhesion [2].

The use of the MQ resin created quite a tradeoff for formulators: while the MQ resin improves long-wear qualities, it also created issues in terms of application, feel, and shine/gloss capability [4]. The MQ resin also contributes to dryness experienced by consumers post application; this is because the silicone derivative in combination with other lipstick ingredients would result in a dry and tightening effect on the lips [7]. The enhanced adhesion to the skin is beneficial in terms of product appearance, durability and consumer experience, but time and time again consumers have criticized the long-wear formulations due to their drying tendency and discomfort. With no hydrating property, application of the formulation to the lips stratum corneum, which is also relatively low in water content, reduces consumer comfort [2]. This effect is also caused by the film itself: a continuous film applies stress on the skin’s keratinous layer which, in turn, translates to the discomfort experienced by the user [8]. A secondary top layer was introduced to the two-step kit in order to help address consumer complaints in regards to durability and performance [2]. A second benefit to the two-step application was the freedom for the consumer to decide what appearance they would like. Rather than solely having a matte option, a shiny topcoat could be used to achieve a satin or sheer effect. Although beneficial, there are limitations to this technology; in order to provide an acceptable level of shine and appearance, the topcoat may need to be re-applied throughout the course of the day and, therefore, cannot truly be classified as long-wearing [4]. At this point, consumers needed to make a tradeoff between appearance and comfort versus the need for constant re-application to achieve the desired shine. This further drove the need for a simple application method that met consumer product requirements through formulation optimization.

Читать дальше