“Guilty to everything,” he confessed, pushing his chair a little nearer to hers and closer to the window. “But then you must remember that the Secret Service of the old order has gone out. The memoirs writer and the novelist have given away our fireworks. We are only subtle now by being terribly and painfully obvious.”

“You may be speaking the truth,” she murmured, “but it seems to me that it must be a dangerous experiment. I could recall to myself the names of at least a dozen people who know that a Major Fawley is here on behalf of a certain branch of the Italian Government to see for himself and report upon the situation. It would be worth the while of more than one of them to make sure that you never returned to Rome.”

“There are certain risks to be run, of course,” he admitted. “The only point is that I came to the conclusion some years ago that one runs them in a more dignified fashion and with just as much chance of success by abandoning the old methods.”

She sat perfectly silent for some time. They were both looking downwards at the thronged and brilliantly lit streets, the surging masses of human beings, listening to the hoarse mutterings of voices punctuated sometimes with the shouting of excited pedestrians. There was a certain tenseness underneath it all. The trampling of feet upon the pavement was like the breaking of an incoming tide. One had the idea of mighty forces straining at a yielding leash. Elida swung suddenly around.

“You play the game of frankness wonderfully,” she said bitterly, “but there are times when you fall down.”

“As for instance?”

“When you make enquiries of the concierge about the air services to Rome. When you send for a time-table to compare the trains and when you slip into the side entrance at Cook’s in the twilight an hour or so later and take your ticket for England!”

“You have had me followed?” he asked.

“It has been necessary,” she told him. “What has England to do with your report to Berati?”

His eyes seemed to be watching the black mass of people below, but he smiled reflectively.

“What an advertisement this last coup of yours is for the open methods of diplomacy,” he observed. “Would it surprise you very much to know that I can take the night plane to Croydon, catch the International Airways to Rome, and be there a little quicker than any way I have discovered yet of sailing over the Alps?”

“Will you turn your head and look at me, please?”

He obeyed at once.

“You are not going to London, then?” she persisted. “Berati has abandoned that old idea of his of seeking English sympathies?”

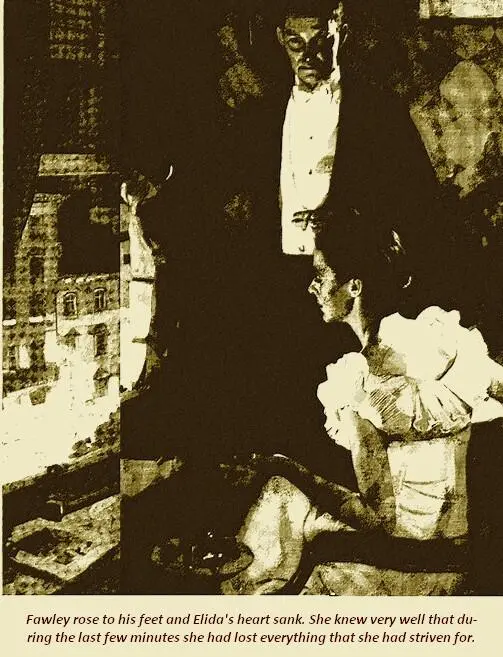

Fawley rose to his feet and Elida’s heart sank. She knew very well that during the last few minutes, ever since, in fact, she had confessed to her surveillance over him, she had lost everything she had striven so hard to gain. Her bid for his supreme confidence had failed. Before she actually realised what had happened, she was moving towards the door. He was speaking meaningless words; his tone, his expression had changed. All the humanity seemed to have left his face. Even the admiration which had gleamed more than once in his eyes and the memory of which she had treasured all the evening had become the admiration of a man for an attractive doll.

“You are under your own roof,” he remarked, as he opened the door. “You will forgive me if I do not offer to conduct you to your aunt’s apartment?”

He bent over her cold fingers.

“Why are you angry with me?” she asked passionately.

He looked at her with a gleam of sadness in his eyes, the knob of the door in his hand.

“My dear Elida,” he expostulated, “you know very well that the only feeling I dare permit myself to have for you is one of sincere admiration.”

Table of Contents

His Excellency the Marchese Marius di Vasena, Ambassador from Italy to the Court of St. James’s, threw himself back in his chair and held out his hands to his unexpected visitor with a gesture of astonishment. He waved his secretary away. It had really been a very anxious week and this was a form of relaxation which appealed to him.

“Elida!” he exclaimed, embracing his favourite niece. “What on earth does this mean? I saw pictures of you last week with all the royalties at Monte Carlo. Has your aunt any idea?”

“Not the slightest,” Elida laughed.

“But how did you arrive?”

“Oh, I just came,” she replied. “I did not arrive direct. I had some places to visit on the way. As a matter of fact, I left Monte Carlo a fortnight ago. Yesterday I was in Paris but I had a sudden feeling that I must see you, dear Uncle. So here I am!”

“And the need for all this haste?” the Ambassador asked courteously, as he arranged an easy-chair for his niece. “If one could only believe that it was impatience to see your elderly but affectionate relative!”

She laughed—a soft rippling effort of mirth.

“I am always happy to see you, my dear Uncle, that you know,” she assured him. “That is why I was so unhappy when you were given London. Yesterday, however, a great desire swept over me.”

“And that was—?”

“To attend the American Ambassador’s dance to-night at Dorrington House. I simply could not resist it. Aunt will not mind. You are going to be very good-natured and take me—yes?”

The smile faded from the Ambassador’s face.

“I suppose that can easily be arranged,” he admitted. “It will not be a very gay affair, though. In diplomatic circles, it is rather our close season.”

Elida—she was certainly a very privileged niece—leaned forward and drew out one of the drawers of her uncle’s handsome writing table. She helped herself to a box of cigarettes and lit one.

“Yet they tell me,” she confided, “I heard it even in Monte Carlo, that just now England or Washington—no one is certain which; perhaps both—are busy forging thunderbolts.”

“No news of it has come my way,” the Ambassador declared, with a benevolent smile. “If one were ever inclined to give credence to absurd rumours, one would look rather nearer home for trouble.”

She leaned over and patted his cheek.

“Dear doyen of all the diplomats, it is not you who would tell your secrets to a little chatterbox of a niece! It seems a pity, for I love being interested.”

“ Carissima ,” he murmured, “to-night at Dorrington House you will find ten or a dozen terribly impressionable young Americans, two or three of them quite fresh from Washington. You will find English statesmen even, who have the reputation of being sensitive to feminine charms such as yours and who have not the accursed handicap of being your uncle. You will find my own youthful staff of budding diplomats, who all imagine that they have secrets locked away in their bosoms far more wonderful than any which have been confided to me. You will be in your glory, dear Elida, and if you find out anything really worth knowing about these thunderbolts, do not forget your poor relations!”

She made a little grimace at him.

“You have always been inclined to make fun of me, have you not, since I became a serious woman?”

The Marchese assumed an austere air and tone.

“I do not make fun of you,” he assured her. “If I am not too happy to see you wrapped up in things which should be left to your elders, it is because there is no excitement without danger, and it was not intended that a young woman so highly placed, so beautiful as you, should court danger.”

Читать дальше