‘I know you better than that,’ he said. ‘Come on, a problem shared and all that.’

Betty knew there was no point in pretending, and the truth was she needed to vent her feelings and worries, which were overtaking her every thought. ‘I know they have to show the newsreels; I just wish they wouldn’t. I can’t bear to see what’s happening. I’m frightened of what might come next.’

Spinning Betty round to face him, he took both of her hands in his. ‘Now listen up,’ he said, ‘everything is going to be all right. Our government won’t let a war happen and, even if they did, Hitler doesn’t stand a chance against the likes of me.’

Betty knew William was only trying to cheer her up – his way of dealing with any upset was to find a way of lightening the mood – but it was his endearing innocence which frightened her the most. Young men like her William saw the idea of war as one big adrenalin-fuelled adventure, a chance to take to the skies and see the world.

‘Oh, my love,’ Betty sighed, looking into William’s kind eyes, ‘I just don’t want to lose you too. I know joining the RAF feels like the right thing to do, and your bravery is one of the many reasons I love you so much.’ Deep down, Betty knew she would struggle to change William’s mind, but she couldn’t just let him go without a fight. ‘Couldn’t you just take a job down the pit?’ she asked, in a last-ditch attempt to convince William it was a much safer option than fighting the Luftwaffe. She knew William adored his job at Coopers, but she’d rather him take his chances six feet underground than flying across Germany’s vast, perilous skies.

‘You have so little faith in me.’ William teased, waggling his finger from side to side. ‘I will be the fastest fighter pilot the world has seen.’ She’d known William long enough to give up her argument, reluctantly accepting he wasn’t going to take the risk seriously. Why would he? His dad hadn’t fought in the war, nor had his uncles – they had all been coal miners. The only problem was that their tales of being stuck in dark and damp mineshafts for hours at a time, nasty black itchy dust collecting in the corner of their eyes, ears and mouths – which, despite a weekly Friday night scrub in a tin bath, never completely disappeared – had put William off a career down the pit for life.

All Betty could do now was hope beyond hope that Neville Chamberlain had what it took to stop Hitler in his tracks and to avoid Britain going to war.

‘Please don’t worry, my lovely, sweet Bet,’ William said, before he gently kissed her goodnight on the doorstep of her boarding house. For once she didn’t bring their lingering embrace to a premature end, as she usually would, even if Mrs Wallis – the rather Victorian in nature and incredibly proper and strict landlady – could see them.

Mrs Wallis kept a tight ship, refused her lodgers to enjoy any visitors, except the odd cup of tea in the communal and very formal front room, ensuring propriety was always the priority. It wouldn’t surprise Betty if her landlady was hovering just a few paces behind the bright-red front door, ensuring her wards – as she liked to view those who took rooms in her rather grand townhouse – were home and safely tucked under their floral patchwork eiderdowns.

Knowing her rather stern landlady was now likely to be only seconds away from coughing or, even worse, opening the front door and catching her and William in a loving embrace, Betty finally, and reluctantly, released herself from William’s warm and naturally protective hold.

‘I’ll call on you tomorrow,’ he said, clinging to Betty’s fingers, desperate to freeze time so they would never have to be parted.

But right on cue, heavy footsteps behind the door broke the tender moment as quick as a bolt of thunder. ‘Goodnight, my love,’ Betty sighed dreamily, giving William one final peck on the cheek.

For a few precious seconds, Betty had temporarily forgotten the foreboding thoughts that had dominated her mind all evening. But as she walked past Mrs Wallis in the corridor, bidding her goodnight and throwing her one of her most innocent smiles, the sense of uncertainty suddenly returned.

After washing her face clean with lukewarm water and lavender-scented soap in the porcelain sink in the corner of her room, Betty changed her pale-blue skirt and cream blouse, on which she could still smell William’s musky aftershave, and slipped into her long, white, crisp cotton nightdress.

Climbing into her cold but familiar bed, she tried to close her eyes as she rested her head upon the fluffy pillow – something Mrs Wallis prided herself on. But as soon as she tried to doze off, worry overcame her once more. To Betty, war seemed an obvious outcome to this whole messy situation, but where would that leave her and William? Would she have to kiss him goodbye if he did follow his heart and join the RAF, telling him she would see him soon, knowing the reality could paint a very different picture?

And what would she do? One thing was for sure: if war was announced, she couldn’t do nothing. She couldn’t just rest on her laurels and hope it would pass; she would have to do her bit.

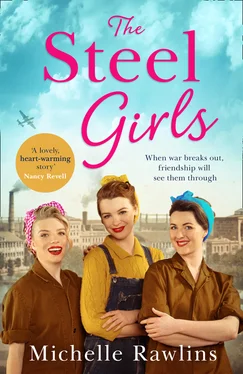

Perhaps she’d have to do as the women of Sheffield did in the First World War and rise to the challenge, stepping into the steel toe-capped boots the city men would leave behind. The steel factories had relied on women to keep the foundry fires burning for four long years and Betty was determined she would be one of the first in line to ensure those sent to war, like her William, had the munitions they needed to fight the battle they faced.

Monday, 28 August 1939

Her arms aching, Nancy wrung the last flannelette sheet through the mangle.

‘Thank the lord for that,’ she said, sighing to herself, desperate for a cuppa after hours of laboriously scrubbing, washing and cleaning. It was Monday, and like most of the women on Prince Street, she had been giving the house a once-over since the crack of dawn. Even before she had safely delivered her two children, Billy, seven, and five-year-old Linda, at school, Nancy had stripped the beds and beat the front-room rug with a brush over the washing line in the back yard.

She had spent the morning scrubbing the front doorstep with a donkey stone, but despite the fact it left her knuckles red raw, and numb with cold when winter came, it was one of the jobs Nancy didn’t mind. Up and down most roads across the city, women could be seen doubled over on their hands and knees, applying as much elbow grease as they did chatter with the neighbours, until their front step was spick and span. No well-respecting housewife would dream of missing the weekly ritual.

‘How you getting on, Doris?’ Nancy asked her good friend and weary-looking neighbour, as she trundled wearily out of her own front door

‘Ah, not so bad.’ Doris smiled, her eyes drooping despite it just turning ten thirty. ‘Nothing a good brew and eight hours of solid sleep wouldn’t sort.’

Nancy didn’t need to ask why. She’d heard Doris’s youngest crying through the walls in the early hours.

‘Georgie?’ Nancy asked, and Doris nodded. ‘He’ll settle soon enough,’ Nancy said reassuringly, but if the truth be known, she had no idea if her well-meant words would come true or not. Little George, as he was also known, hadn’t slept through a single night since his dad – ‘Big George’, Doris’s husband – had been tragically killed at Vickers, the local steelworks. And by the look of it – neither had Doris. The heavy bags under her eyes grew darker by the day and her frail frame seemed to be visibly shrinking.

‘Are you sure you’re managing?’ Nancy asked kindly. ‘Why don’t you let me have the kids over for tea and you can catch forty winks.’

Читать дальше