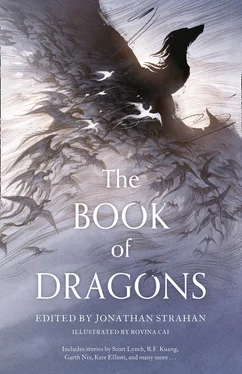

AN ANTHOLOGY

EDITED BY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ROVINA CAI

Harper Voyager

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2020

Collection and introduction copyright © Jonathan Strahan 2020

The chapter ‘Credits’ constitutes an extension of this copyright page

Illustrations © Rovina Cai

Cover illustrations © Rovina Cai 2020

Cover layout design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2020

The author of each individual story asserts their moral rights, including the right to be identified as the author of their work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008331474

Ebook Edition © May 2020 ISBN: 9780008331498

Version: 2020-06-08

For Jessica and Sophie,

in memory of Princess Jasmine

and her best friend, Marmaduke,

and for all of the dragons that have helped

keep our dreams safe.

My armor is like tenfold shields, my teeth are swords, my claws spears, the shock of my tail a thunderbolt, my wings a hurricane, and my breath death!

—J. R. R. TOLKIEN, The Hobbit, or There and Back Again

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

Introduction

“What Heroism Tells Us,” Jane Yolen

“Matriculation,” Elle Katharine White

“Hikayat Sri Bujang, or, The Tale of the Naga Sage,” Zen Cho

“Yuli,” Daniel Abraham

“A Whisper of Blue,” Ken Liu

“Nidhog,” Jo Walton

“Where the River Turns to Concrete,” Brooke Bolander

“Habitat,” K. J. Parker

“Pox,” Ellen Klages

“The Nine Curves River,” R. F. Kuang

“Lucky’s Dragon,” Kelly Barnhill

“I Make Myself a Dragon,” Beth Cato

“The Exile,” JY Yang

“Except on Saturdays,” Peter S. Beagle

“La Vitesse,” Kelly Robson

“A Final Knight to Her Love and Foe,” Amal El-Mohtar

“The Long Walk,” Kate Elliott

“Cut Me Another Quill, Mister Fitz,” Garth Nix

“Hoard,” Seanan McGuire

“The Wyrm of Lirr,” C. S. E. Cooney

“The Last Hunt,” Aliette de Bodard

“We Continue,” Ann Leckie and Rachel Swirsky

“Small Bird’s Plea,” Todd McCaffrey

“The Dragons,” Theodora Goss

“Dragon Slayer,” Michael Swanwick

“Camouflage,” Patricia A. McKillip

“We Don’t Talk About the Dragon,” Sarah Gailey

“Maybe Just Go Up There and Talk to It,” Scott Lynch

“A Nice Cuppa,” Jane Yolen

ABOUT OUR POETS

CREDITS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT JONATHAN STRAHAN

ALSO EDITED BY JONATHAN STRAHAN

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

When my two daughters were very young, I used to tell them bedtime stories. I’d make the stories up each night but never managed to write them down (much to my youngest daughter’s frustration). They were stories about a girl named Jasmine—who lived not far from their grandmother’s house and who kept her dreams in a snow globe on her bedroom dresser, safe from a witch who sought to steal them—and of her best friend, a small orange dragon named Marmaduke, who was wise and brave and helped Jasmine to understand how she could save herself. Marmaduke even engaged in some glassblowing, not too long after a family vacation during which we watched a glassblower at work. The memories are hazy, but I think the glassblowing had something to do with the unmaking of the world, which seemed a lot for such a tiny dragon, but magic can make heroes of us all.

My own first memory of dragons, if it’s possible to isolate such memories, given how pervasive dragons are in our culture, is probably Pete in the not-particularly-excellent Disney film Pete’s Dragon , in which a young boy finds an invisible friend, Elliot, who helps him when he needs it most and brings adventure into his life. If I can’t quite be sure about the first dragon I encountered, it’s hard to forget the many that followed: the greatest wyrm of them all, Tolkien’s Smaug, raining fire down on Lake-town in The Hobbit ; followed by Yevaud and the archipelagos of Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea ; the white dragon, Ruth, from Anne McCaffrey’s Pern; Naomi Novik’s Temeraire; and George R. R. Martin’s dragons of Westeros: Rhaegal, Viserion, and Drogon.

What do all of these great and mighty dragons have in common? Perhaps that they reflect some aspect of ourselves back to us through story. They can be wise friends and counselors, devious enemies and fiery opponents, and pretty much everything in between. Mayland Long in R. A. MacAvoy’s Tea with the Black Dragon is a wealthy older man who simply wants to help a mother find her daughter, but it seems he is also a two-thousand-year-old dragon. Lucius Shepard’s great and maligned Griaule from The Dragon Griaule , possibly the greatest dragon to enter fantasy literature in the past thirty years, is a slumbering beast the size of a mountain range on which towns and villages are built, and whose human population both depends upon and hates him in equal measure. Dragons, it seems, have always been with us in story, and although I am not a researcher of folktales or an ethnologist, I could be convinced that dragons can be traced back to the first fires around which our distant ancestors gathered, inspired by dark places beyond the light of the fire and the reptiles that lived there—I’m much more skeptical that they are some sort of species memory of dinosaurs, but let’s not rule that out.

Regardless, the way we see dragons depends on where we are in the world. In the West, the image of the fire-breathing, four-legged, winged beast arose in the High Middle Ages. Perhaps a variation on Satan, the Western dragon is often evil, greedy, and clever, and usually hoarding some terrible treasure. There are the dragons of the East, long, snakelike creatures seen as symbols of good fortune and associated with water. Serpentine dragons, like the naga, are found in India and in many Hindu cultures, and are similar to the Indonesian naga or nogo dragons. Japanese dragons, like Ryūjin, the dragon god of the sea, are also water creatures. And so on and so on around the world.

Читать дальше