What is critically important is the functional architecture of this hierarchical system. Current models consider that the system is characterized by a distributed, network‐like architecture in which representations at each level of processing are realized as patterns of activation with properties of activation, inhibition, and competition (McClelland & Elman, 1986; McClelland & Rumelhart, 1986; Gaskell & Marslen‐Wilson, 1999). Not only do the dynamic properties of the network influence the degree to which a particular representation (e.g. a feature, a segment, a word) is activated or inhibited, but patterns of activation also spread to other representations that share particular structural properties. It is also assumed that the system is interactive with information flow being bidirectional; lower levels of representations may influence higher levels, and higher levels may influence lower levels. Thus, there is spreading activation not only within a level of representation (e.g. within the lexical network), but also between and within different levels of representation (e.g. phonological, lexical, and semantic levels).

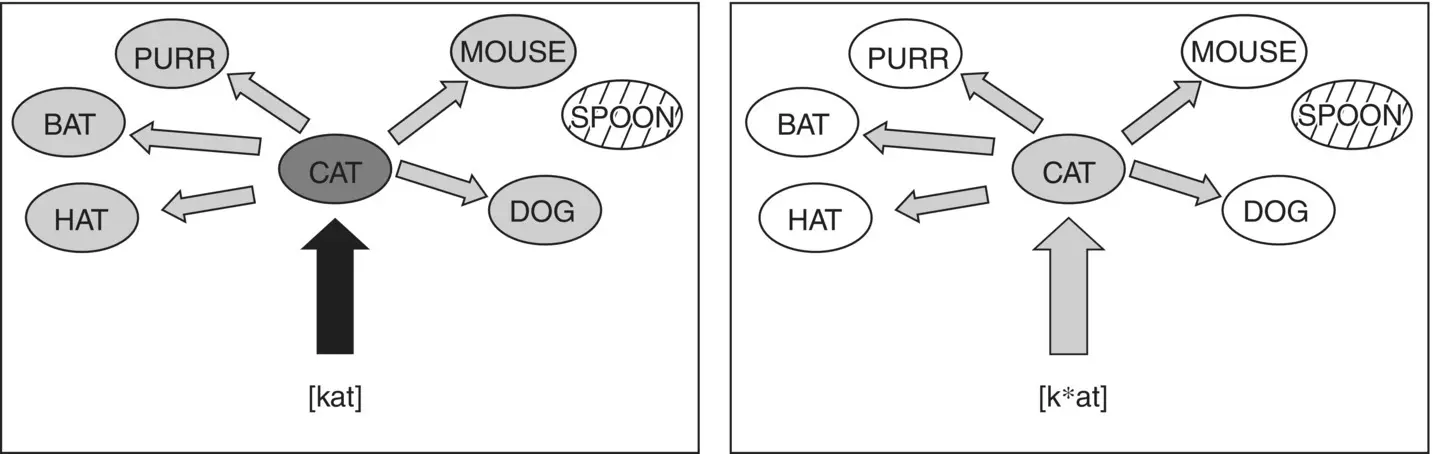

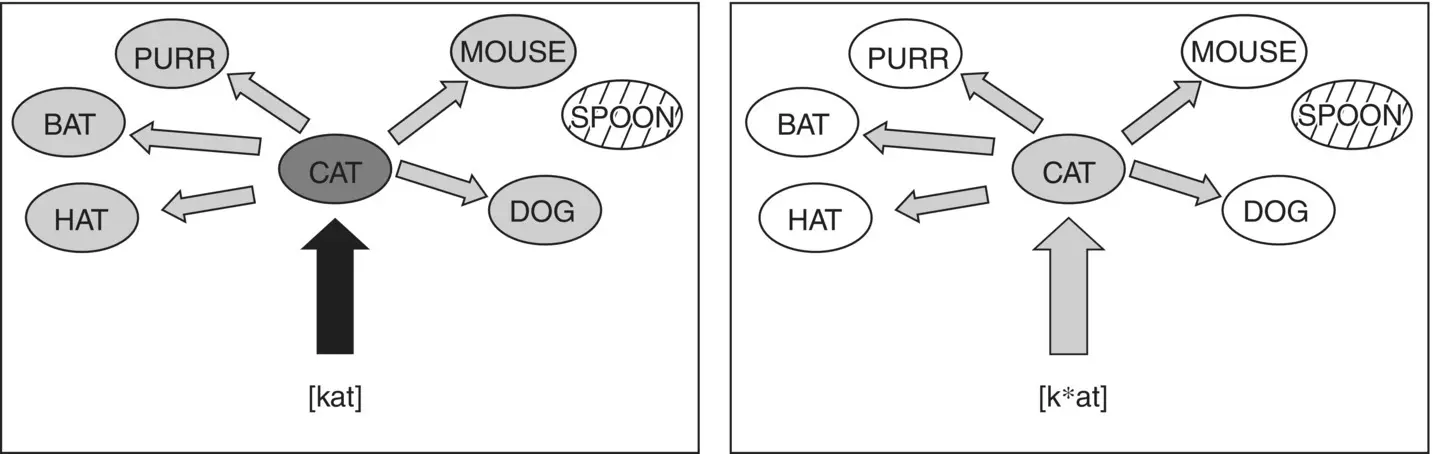

There are several consequences of such a functional architecture, as shown in Figure 5.1. First, there is graded activation throughout the speech‐lexical processing system; that is, the extent to which a given representation is activated is a function of the “goodness” of the input. Thus, the activation of a potential candidate is not all‐or‐none but rather is graded or probabilistic. For example, the activation of a phonetic category such as [k] will be influenced by the extent to which the acoustic‐phonetic input matches its representation. It is worth noting that graded activation is more complex than simply the extent to which a particular phonetic attribute matches its representation. Rather, the extent of activation reflects the totality of the acoustic properties giving rise to a particular phonetic category. Thus, the activation of the phonetic feature [voicing] would include the probabilities of voice onset time, burst amplitude and duration, fundamental frequency, to name a few (see Lisker, 1986). Second, because the system is interactive, activation patterns at one level of processing will influence activation at another level of processing. For example, a poor acoustic‐phonetic exemplar of a phonetic category such as [k] will influence the activation of the lexical representation of a word target such as cat .

Figure 5.1 Several properties of the functional architecture of auditory word recognition and lexical processing are shown, including graded activation, lexical competition, and interactivity (cascading activation). The left and right panels show how one level of processing influences activation of another downstream from it in an interactive system. The left panel shows activation of a good phonetic exemplar [kat] on activation of the lexical representation cat and the graded activation of phonological and semantic competitors in its lexical network. Note spoon which is neither phonologically nor semantically related is not activated. The right panel shows the cascading effects of a poor phonetic input [k*at] on the network. There is reduced activation of its lexical representation and even greater reduction of activation of competitors.

Third, because of the network properties of the system and the structure of the representations, there is competition between potential candidates at each stage of processing (e.g. within the sound [segment and feature], lexical, and semantic levels of representation). The degree of competition is a function of the extent to which the candidate(s) share(s) properties with the particular target. This influences the time course and patterns of activation of the target and, ultimately, the performance of the network. Multiple competing representations may also influence activation and processing at other stages of processing (Gaskell & Marslen‐Wilson, 1999; McClelland, 1979). These properties of the functional architecture of the system – graded activation, interactivity, and competition – influence lexical representations. As we will see, each of these properties provides evidence for features as representational units.

Distinctive features as a theoretical construct

The theoretical foundations for features come from linguistics, and in particular from phonology (the study of the sound systems of language). Phonological evidence for features as a theoretical construct is based on consideration of (1) the nature of the phonological inventories across languages; (2) the phonological processes of languages synchronically, that is, at a particular point in time; and (3) the processes by which sound inventories in language change historically, that is, over time.

To begin, it is assumed that the sound segments of language are composed of a smaller set of features or parameters of sound (at this point, we will not focus on whether the features are acoustically or articulatorily based, nor will we describe them in detail). These parameters reflect the fact that the phonetic segments (phonetic categories) of language can be further broken down into general classes. These classes are attributes that characterize how a sound may be produced or perceived, including whether the phonetic segment is a consonant or vowel; its manner of articulation (e.g. stop, nasal, fricative); where in the mouth the articulation occurs, for example, at the lips (labial), behind the teeth (alveolar), or at the velum (velar); and the laryngeal state of the production (e.g. voiced or voiceless). Thus, segments (phonetic categories) that share features are closer in articulatory or acoustic space than those that do not. As we shall see, this has ramifications for the performance of listeners in the perception of speech.

The basic notion that underlies the study of phonology is that sound inventories of language are not composed of a random selection of potential phonetic categories. Rather, sound segments tend to group into natural classes reflecting shared sets of feature parameters, for example, manner of articulation (obstruent, continuant, nasal), place of articulation (labial, alveolar, palatal, velar), or the state of the glottis (voicing). Speech inventories across languages also tend toward symmetry. For example, a language inventory may have voiced and voiceless stop labial, alveolar, and velar consonants, as in English, but would typically not have an inventory consisting solely of a voiceless labial, voiced alveolar, and voiceless palatal stop consonant.

Synchronically, languages have phonological processes (called morphophonemic rules) in which phonemic changes occur to morphemes (minimal units of sound–meaning relations) when they combine with other morphemes to form words. Such changes are typically systematic changes to particular features. For example, in English, a plural morpheme {s} is realized phonetically as an [s] when it is preceded by a word ending in a voiceless obstruent, for example, book [s]; it is realized as a [z] when it is preceded by a voiced obstruent, for example, dog [z]; and it is realized as the syllable [əz] when it is preceded by a fricative, for example, horse [əz]. Interestingly, the same morphophonemic processes occur in English for possessives, for example, Dick’s book , Doug’s book , Gladys’ book , and for the third singular, for example, he kicks/jogs/kisses .

Historically, language systems change over time. Again, such changes typically involve changes in features. Moreover, many changes involve changes not to one phonetic segment in the language inventory but to a class of sounds. Two such changes are the Great Vowel Shift and Grimm’s law. In the Great Vowel Shift, as Modern English developed from Middle English, features of vowels systematically changed: low vowels became mid‐vowels, mid‐vowels became high vowels, and high vowels became diphthongs. Grimm’s law affected features of consonants: voiceless stops became voiceless fricatives (a change in the feature [obstruent]); voiced stops became voiceless stops, and voiced aspirated stops became voiced stops or fricatives (both changes of laryngeal features) as German developed from Proto‐Indo‐European.

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Справочник Гименея [The Handbook of Hymen]](/books/407356/o-genri-spravochnik-gimeneya-the-handbook-of-hymen-thumb.webp)