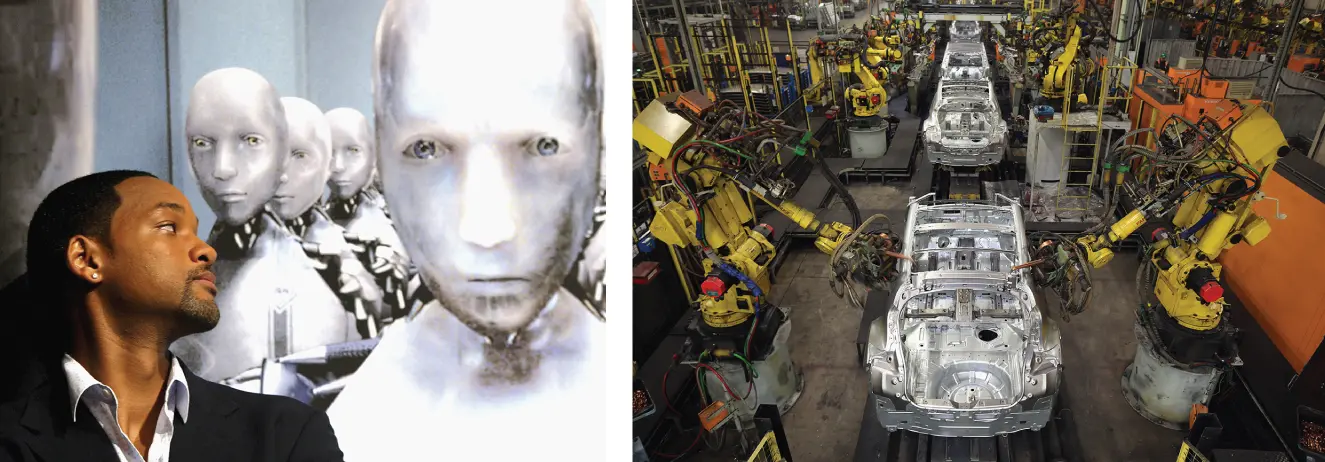

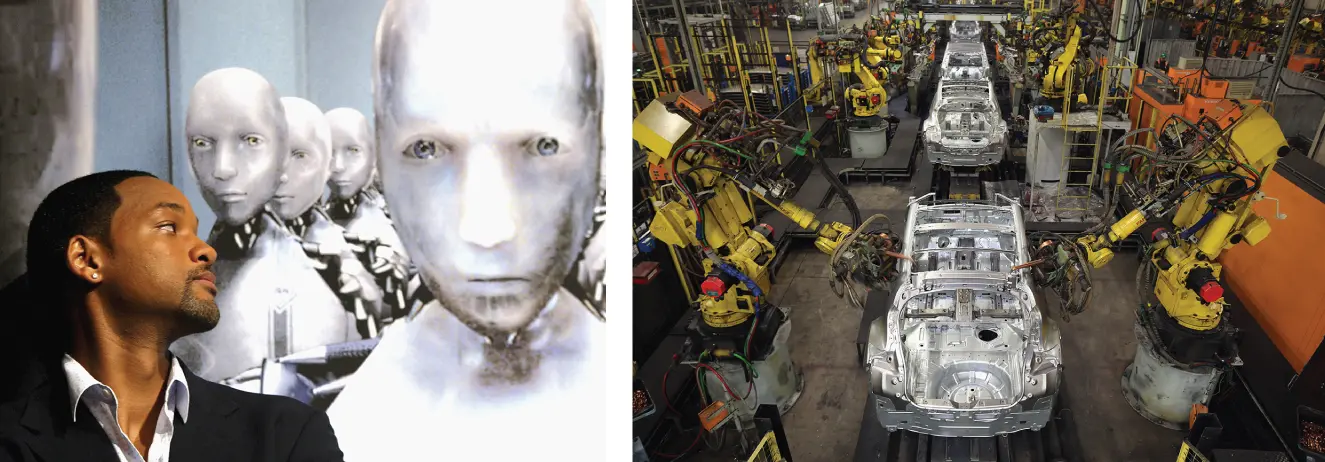

FIGURE 1.2 : Hollywood robots (left), like humans, can move in complex environments, but that's true only in the movies. Most real-life robots (right) move in predictable environments. Our ability to see and move is a remarkable cognitive feat.

Source: Hollywood robots © Getty Images/Koichi Kamoshida; factory robots © Getty Images/Christopher Furlong.

Compared to your ability to see and move, thinking is slow, effortful, and uncertain. To get a feel for why I say this, try solving this problem:

In an empty room are a candle, some matches, and a box of tacks. The goal is to have the lit candle about 5 ft off the ground. You've tried melting some of the wax on the bottom of the candle and sticking it to the wall, but that wasn't effective. How can you get the lit candle 5 ft off the ground without having to hold it there? 2

Twenty minutes is the usual maximum time allowed, and few people are able to solve it by then, although once you hear the answer you will realize it's not especially tricky. You dump the tacks out of the box, tack the box to the wall, and use it as a platform for the candle.

This problem illustrates three properties of thinking. First, thinking is slow. Your visual system instantly takes in a complex scene. When you enter a friend's backyard you don't think to yourself, “Hmmm, there's some green stuff. Probably grass, but it could be some other ground cover – and what's that rough brown object sticking up there? A fence, perhaps?” You take in the whole scene – lawn, fence, flowerbeds, gazebo – at a glance. Your thinking system does not instantly calculate the answer to a problem the way your visual system immediately takes in a visual scene. Second, thinking is effortful; you don't have to try to see, but thinking takes concentration. You can perform other tasks while you are seeing, but you can't think about something else while you are working on a problem. Finally, thinking is uncertain. Your visual system seldom makes mistakes, and when it does you usually think you see something similar to what is actually out there – you're close, if not exactly right. Your thinking system might not even get you close. In fact, your thinking system may not produce an answer at all, which is what happens to most people when they try to solve the candle problem.

If we're all so bad at thinking, how does anyone get through the day? How do we find our way to work or spot a bargain at the grocery store? How does a teacher make the hundreds of decisions necessary to get through her day? The answer is that when we can get away with it, we don't think. Instead we rely on memory. Most of the problems we face are ones we've solved before, so we just do what we've done in the past. For example, suppose that next week a friend gives you the candle problem. You would immediately say, “Oh, right. I've heard this one. You tack the box to the wall.” Just as your visual system takes in a scene and, without any effort on your part, tells you what is in the environment, so too your memory system immediately and effortlessly recognizes that you've heard the problem before and provides the answer. You may think you have a terrible memory, and it's true that your memory system is not as reliable as your visual or movement system – sometimes you forget, sometimes you think you remember when you don't – but your memory system is much more reliable than your thinking system, and it provides answers quickly and with little effort.

We normally think of memory as storing personal events (memories of my wedding) and facts (the seat of the Coptic Orthodox Church is in Egypt). Our memory also stores strategies to guide what we should do: where to turn when driving home, how to handle a minor dispute when monitoring recess, what to do when a pot on the stove starts to boil over ( Figure 1.3). For the vast majority of decisions we make, we don't stop to consider what we might do, reason about it, anticipate possible consequences, and so on. For example, when I decide to make spaghetti for dinner, I don't scour the Internet for recipes, weighing each for taste, nutritional value, ease of preparation, cost of ingredients, visual appeal, and so on – I just make spaghetti sauce the way I usually do. As two psychologists put it, “Most of the time what we do is what we do most of the time.” 3When you feel as though you are “on autopilot,” even if you're doing something rather complex, such as driving home from school, it's because you are using memory to guide your behavior. Using memory doesn't require much of your attention, so you are free to daydream, even as you're stopping at red lights, passing cars, watching for pedestrians, and so on.

FIGURE 1.3 : Your memory system operates so quickly and effortlessly that you seldom notice it working. For example, your memory has stored away information about what things look like (Gandhi's face) and how to manipulate objects (turn the left faucet for hot water, the right for cold) and strategies for dealing with problems you've encountered before (such as a pot boiling over).

Source: Gandhi © Getty Images/Dinodia Photos; faucet © Shutterstock/RVillalon; pot © Shutterstock/Andrey_Popov.

Of course you could make each decision with care and thought. When someone encourages you to “think outside the box” that's usually what he means – don't go on autopilot, don't do what you (or others) have always done. Consider what life would be like if you always strove to think outside the box. Suppose you approached every task afresh and tried to see all of its possibilities, even daily tasks like chopping an onion, entering your workplace, or sending a text message. The novelty might be fun for a while, but life would soon be exhausting ( Figure 1.4).

FIGURE 1.4 : “Thinking outside the box” for a mundane task like selecting bread at the supermarket would probably not be worth the mental effort.

Source: © Shutterstock/B Brown.

You may have experienced something similar when traveling, especially if you've traveled where you don't speak the local language. Everything is unfamiliar and even trivial actions demand lots of thought. For example, buying a soft drink from a vendor requires figuring out the flavors from the exotic packaging, trying to communicate with the vendor, working through which coin or bill to use, and so on. That's one reason that traveling is so tiring: all of the trivial actions that at home could be made on autopilot require your full attention.

So far I've described two ways in which your brain is set up to save you from having to think. First, some of the most important functions (for example, vision and movement) don't require thought: you don't have to reason about what you see; you just immediately know what's out in the world. Second, you are biased to use memory to guide your actions rather than to think. But your brain doesn't leave it there; it is capable of changing in order to save you from having to think. If you repeat the same thought-demanding task again and again, it will eventually become automatic; your brain will change so that you can complete the task without thinking about it. I discuss this process in more detail in Chapter 5, but a familiar example here will illustrate what I mean. You can probably recall that learning to drive a car was mentally very demanding. I remember focusing on how hard to depress the accelerator, when to apply the brake as I approached a red light, how far to turn the steering wheel to execute a turn, when to check my mirrors, and so forth. I didn't even listen to music while I drove, for fear of being distracted. With practice, however, the process of driving became automatic, and now I don't need to think about those small-scale bits of driving any more than I need to think about how to walk. I can drive while simultaneously chatting with friends, gesturing with one hand, and eating French fries – an impressive cognitive feat, if not very attractive to watch. †Thus a task that initially takes a great deal of thought becomes, with practice, a task that requires little thought.

Читать дальше