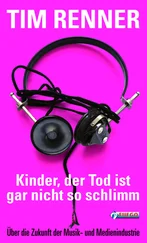

Tim Renner

DEATH IS NOT SO BAD!

On the future of the music and media industry

FUEGO

- ABOUT THIS BOOK -

When Tim Renner applied to the German record company Polydor in 1986, he intended to write an exposé about the music industry. However, things went differently and he turned this exposé into a career. For eighteen years his biography has been intermeshed with the development of the music industry, he led bands like Element of Crime, Rammstein, Tocotronic and Philip Boa to sucess. He raised up higher and higher on the ladder, finally reaching the top of Universal Music Germany. He witnessed how musical development has been hampered by the pressure of the markets, how pop and commerce diffused, and importantly, he witnessed the rapid dissolution of old comercial structures through the forces of digitalzation and globalization. But the ponderous giant labels kept their eyes shut in front of these developments and Renner finally quit. After his leave from Universal in 2004 he described his point of view on what he found were wrong tracks and challenges of contemporary pop music.

»Death is not bad!« is a profound analysis of culture and music in times of digitalization, based on the vison that creativity, consumption and capital could find a way of coexistence.

Ten years after the German edition of this book was published some passages read like a history book about a long forgotten time. Some passages pointing to developments which are fully manifested today and look to evolve further in the future. The book shows the changes of a whole industry and the first steps of a society on it's way into the digitalized future.

INTRODUCTION

This is the story of a failure. My failure. After all, I did not enter the music business 18 years ago in order to have a career. On the contrary, I wanted to unmask the industry. My job as a so-called junior A&R and product manager with music group PolyGram (in other words a scout who discovers artists, organizes and supervises their recordings, and dreams up marketing campaigns to coincide with the release of their records) was a disguise. As an undercover journalist I wanted to conduct clandestine research and turn my discoveries into the first German exposé of the music industry.

My plan failed completely. This book is not the belated fruit of my original ambition to become the Bob Woodward of the music world, for my aim here is not to expose the industry as such. At best I would be able to reveal that the industry is not malevolent – as I believed at the time – but stupid. But who could get excited about that? And would it really be appropriate to base a book on finding humor in an industry’s misfortune? A more interesting approach would be to see the industry as a seismograph.

The tremors of digitalization could have been felt in the music business well over a decade ago if only anyone had had the will to do so. The business has been battered for some considerable time by the crisis of content that can occur when capital is allowed to clash, unrestrained and improperly managed, with culture. The battle between the public, artists, and managers for identity, differentiation and, of course, power, has forever been part of the plot. The future of the media industry therefore has more than a little in common with the past of the music business.

My pupils, at my job interview in June 1986, were dilated. I allowed the two Polydor managers who sat facing me to ask precisely three questions. Then I talked almost uninterrupted for more than an hour. Shortly before the interview I had suffered a hay fever attack and Avil, a brand new medication prescribed by my doctor, had produced some strong side effects. It has now been taken off the market, but back then, right before my interview, it caused my girlfriend Petra to find me slumped over the kitchen table. There was no way she could let me go to my interview in that state. A half bottle of Sekt, German sparkling wine, would be just the thing to give me the kick-start I needed, she thought. This cocktail of Sekt and Avil turned out to be a perfect substitute for speed. Later we used it from time to time when we were out partying.

I sat there at my interview with jittery legs, staring at the Polydor catalog. Listed were the names of all the German artists under contract to the record company, (which was owned by the PolyGram group). A catalog of horrors, I thought then as a 21year-old, and told my astonished interviewers as much: this artist should have been dropped years ago, that artist should have been banned completely from playing or performing, and a third should consider retraining as a homeopath. In my opinion they were all too old, and I made it clear that I thought Polydor had been doing a lousy job for years. In almost any other industry that would have started the countdown to the end of my interview and seconds later the impertinent Tim Renner, who also gave every appearance of being a drugs-user, would have been ejected from the building by a well-aimed kick up the backside. Instead, the Polydor CEO and the head of national repertoire listened attentively. They had long been aware that the industry sold revolution via pressed vinyl, and this youngster had just hoisted a red flag in their office. My contract arrived in the mail the next day.

The story of pop music has always been one of rebellion. The horrors of war were resisted with swing, the middle-class cosiness of the 1950s – and the racism that was never far away – with “Negro music” (otherwise known as rock ’n’ roll), the parental generation burdened by war guilt (whose at best harmless hits were meant to help them forget the past) with earnest singersongwriters, the hippies, with their eternal striving for meaning and security with coarse punk, and the 68ers, schooled in critical theory, with minimalist, “cold” techno. Popular music is youth’s first form of self-expression and will always be so. From a technical point of view, music can be easier to produce than almost any other art form. To get started, all you need are three chords (this we discovered with punk if not before) or alternatively two record players, a mixer, and a bit of practice. The results make themselves felt very quickly: you can be admired on stage or else make an enemy of your parents at home with all the noise.

Initially, rock and pop music are all about two things: sexuality and differentiation. Later, as one gets older, a third can be added: the desire for eternal youth.

No computer game can replace the special bond between live performance and audience. At your computer or games console you play alone or at best networked. On the other hand, the concert or party at which a DJ performs is always a collective and intensely physical experience. Young people who are not yet sure how to approach members of the opposite sex, how to talk to them or win them over, have music and movement as a bridge. Enviable are those who find themselves on stage or standing behind the turntables. If you are not one of them you should at least know the guitarist or be able to give an informed appraisal of the songs and performances of the protagonists in order to make sure you don’t end up in the dark on your own afterward. Once this pattern has been learned and internalized, it continues to function for years after puberty and at the same time guarantees generation after generation of new pop fans.

For a long time now, most consumers of pop music have been over 30, but the renewal of the art form still comes from the young. In music they discover forms of expression that are not immediately comprehensible to parents and teachers; music helps them to discover their personalities. Only when we realize we are individuals in our own right can we become truly independent.

But this process of differentiation becomes more and more difficult from generation to generation. Recently, with techno music, it has been achieved in innovative fashion through the total elimination of any traditional song structure. However, it’s a godsend that pop music as a cultural form is so closely associated with puberty. It ensures that it is continually being called into question. This makes it the most innovative of art forms, and because there is such an urgent need for it, one of the most commercial.

Читать дальше