1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...35

All hominins and African apes lack external tails

Humans and the African apes all lack external tails. Monkeys, on the other hand, do have tails, which are useful for gripping trees and objects. Tails disappeared from apes 15–20 million years ago. Apes shin up and down trees rather than walking along branches as monkeys do. The earliest hominins climbed trees and walked on the ground. Fossil evidence shows how early humans made a gradual transition from climbing trees to walking upright on a regular basis.

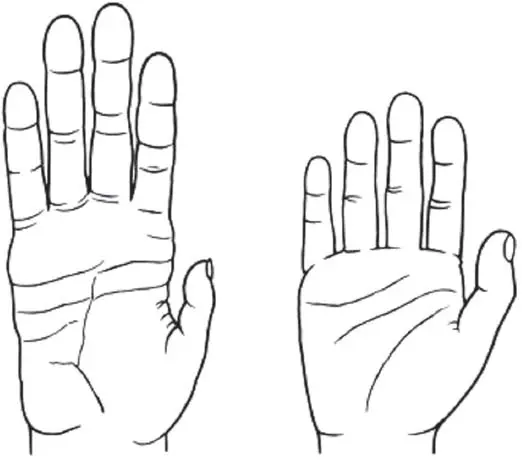

All humans and African apes have opposable thumbs

Both humans and African apes have hands with a thumb that is sufficiently separate from the other fingers to allow them to be opposable for precision grip. Possession of an opposable thumbmeans that objects can be carried more easily and manipulated. There is considerable evidence to suggest that, by being able to throw and powerfully grip an object, early humans were better at protecting themselves from animals and other humans (Young 2003). The development of the opposable thumb, however, primarily helped humans to make tools, which was an essential advantage in human cultural evolution. But the mere presence of the opposable thumb does not explain why humans make sophisticated tools: if it did, then chimpanzees would make complex tools too (and they do not).

opposable thumbA thumb that is sufficiently separate from the other fingers of the hand to allow for precision grip

Figure 1.1Hand of an African ape and of a human. (Denise Morgan for the University of Utah / Wikimedia Commons)

Take off your shoes and socks and sit on the floor. Try to open a banana skin with only your feet. What happens? What does this activity tell us about the advantages of having opposable thumbs?

Make a list of things that early humans might have been able to do as a result of having opposable thumbs. How might these activities have helped humans to survive?

Sexual dimorphismrefers to both the internal and the external differences between males and females found in a variety of animals and plants. The earliest fossil evidence to show sexual dimorphism in early primates demonstrates that canine teeth and body shapes were different in males and females (Krishtalka et al. 1990). Hominins have not shown dimorphism in canine size, but there was a significant level of body size dimorphism in early hominins such as australopithecines. However, sexual dimorphism was significantly reduced in the larger-brained Homo erectus and their descendants (including Homo sapiens ). This suggests an important development in social organization, with a possible change from polygamy (frequently associated with larger males) to monogamy (often characterized by low sexual dimorphism). Modern humans are sexually dimorphic to some degree. It is estimated that males are 5 to 10 per cent larger on average and have greater upper body muscular development. This is small compared to over 100 per cent body size dimorphism in gorillas and at least 15–20 per cent in chimpanzees and bonobos.

sexual dimorphismThis refers to both the internal and the external differences between males and females found in a variety of animals and plants

STOP & THINK

Suggest some reasons for the gradual reduction in human sexual dimorphism.

Like chimpanzees and bonobos, humans are omnivorous; this means that humans and chimpanzees kill other animals for food in addition to eating a wide variety of plants. Essentially, the human body is similar to that of the great apes; humans have the same arrangement of internal organs and bones, share several important blood types and suffer from many of the same diseases. However, there is a significant difference in the amount of meat that humans eat compared to chimpanzees. While chimpanzees extract at most 5 to 10 per cent of their calories from animals (including both small monkeys and termites extracted with tools), Homo erectus obtained most energy from meat (either from scavenging or from hunting). This heavy reliance on meat lasted until very recently, when agriculture appeared. There are only a handful of human populations (fewer than fifty across the globe) still able to survive without agriculture: they are known as hunter-gatherers.

omnivorous Abilityto eat and survive on both plant and animal matter

hunter-gatherersMembers of a nomadic people who live chiefly by hunting and fishing and harvesting wild food

STOP & THINK

What are the advantages of an omnivorous diet?

Competitiveness, hierarchy and aggression

One controversial characteristic that we may share with other primates is the potential for aggression. Field studies have shown differences among nonhuman primate species in the incidence and circumstances of actual intraspecific (within-species) violence. In anthropology, there has been much debate about the human capacity for violence and aggression. Sociobiology, for example, is an area of scientific research and thinking that claims that some social behaviour is a product of evolution (although not all sociobiologists agree on the extent of this). Some argue that certain behaviours (such as aggression and competitiveness) may have been advantageous to human survival. E. O. Wilson (1978), one of the founders of modern sociobiology, described some behaviours thought to be human universals as genetically based, such as male–female bonds, male dominance over females and aggression. These claims have been disputed by many human scientists, who have shown that there is much more variation in patterns of social behaviour across human societies.

sociobiologyAn area of biology that aims to explain social behaviour in terms of evolution

More recently, biological anthropologists such as Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson (1997) have argued that violence played an important role in the evolution of humans and chimpanzees. However, such views have been heavily criticized for their lack of supporting evidence. An alternative view gaining strength in evolutionary anthropology is that our capacity for cooperation is what made humans behaviourally unique. While other species of primates mostly show alliances among closely related kin, studies of hunter-gatherers have shown that we frequently exhibit cooperative behaviours (such as food-sharing) towards those who are unrelated. Some of us are even able to display cooperation and altruism towards unknown individuals (think about giving blood or about charity work). The reasons for the coexistence of extreme cooperation and aggression in human societies is one of the most debated issues in evolutionary anthropology.

Humans and some nonhuman primates share certain similarities in their behaviour towards each other. However, social behaviour varies from species to species. Two examples of nonhuman primate behaviour are explored here: of bonobos and of chimpanzees, our two closest evolutionary relatives.

Bonobos  (© LaggedOnUser / Flickr) Bonobos, found living in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have been noted for their sociability. Groups of bonobos range from about 50 to 100 individuals; however, these groups do break up during the day to form foraging parties. Every night bonobos make a sleeping nest from branches and leaves, usually nesting with the smaller group they have travelled with. Bonobo societies are female-centred in structure. Interestingly, like humans, bonobos have sex for purposes other than reproduction. They often manage and resolve social conflicts through sex, making aggression less common than with chimpanzees. In fact, sex is a very important part of the social relations of bonobos. They engage in both homosexual and heterosexual relations, although incest is generally avoided. Sexual interactions occur more often among bonobos than among other primates. Despite the frequency of sex, their rate of reproduction in the wild is about the same as that of the chimpanzee. Bonobo communities have ranges that overlap with other groups. Males are protective of other members of their group and carry out any hunting. Males typically remain among their family group while females range further afield. While males show aggression towards each other, conflict rarely escalates into acts of physical violence. In spite of physical superiority, evidence suggests that males are not aggressive towards females. Bonobos are social animals, and food sharing occurs between males and females, unlike the situation with chimpanzees. Also the female–female relationship is much stronger in this species than it is for chimpanzees. Although they seem very lively, bonobos, like humans, control their emotions when expressing themselves in times of happiness, sorrow, excitement or anger. They are very animated and perform similar gestures to humans when communicating without using language. For example, they will beg by stretching out an open hand or foot and will make a whimpering sound if they fail at something. Females become sexually mature after about twelve years of age and may give birth soon thereafter. They have babies at five- to six-year intervals, so population growth can never be rapid. As with humans, there is a relatively long period of socialization for the young. Females nurse and carry their babies for five years, and the offspring reach adolescence by the age of seven. Females have between five and six offspring in a lifetime. (© LaggedOnUser / Flickr) Bonobos, found living in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have been noted for their sociability. Groups of bonobos range from about 50 to 100 individuals; however, these groups do break up during the day to form foraging parties. Every night bonobos make a sleeping nest from branches and leaves, usually nesting with the smaller group they have travelled with. Bonobo societies are female-centred in structure. Interestingly, like humans, bonobos have sex for purposes other than reproduction. They often manage and resolve social conflicts through sex, making aggression less common than with chimpanzees. In fact, sex is a very important part of the social relations of bonobos. They engage in both homosexual and heterosexual relations, although incest is generally avoided. Sexual interactions occur more often among bonobos than among other primates. Despite the frequency of sex, their rate of reproduction in the wild is about the same as that of the chimpanzee. Bonobo communities have ranges that overlap with other groups. Males are protective of other members of their group and carry out any hunting. Males typically remain among their family group while females range further afield. While males show aggression towards each other, conflict rarely escalates into acts of physical violence. In spite of physical superiority, evidence suggests that males are not aggressive towards females. Bonobos are social animals, and food sharing occurs between males and females, unlike the situation with chimpanzees. Also the female–female relationship is much stronger in this species than it is for chimpanzees. Although they seem very lively, bonobos, like humans, control their emotions when expressing themselves in times of happiness, sorrow, excitement or anger. They are very animated and perform similar gestures to humans when communicating without using language. For example, they will beg by stretching out an open hand or foot and will make a whimpering sound if they fail at something. Females become sexually mature after about twelve years of age and may give birth soon thereafter. They have babies at five- to six-year intervals, so population growth can never be rapid. As with humans, there is a relatively long period of socialization for the young. Females nurse and carry their babies for five years, and the offspring reach adolescence by the age of seven. Females have between five and six offspring in a lifetime. |

Chimpanzees  (Matthew Hoelscher / Wikimedia Commons) Common chimpanzees, living in tropical forests of Africa, live in small communities. These typically range from 20 to more than 150 members; however, chimpanzees spend most of their time travelling in small, temporary groups consisting of a few individuals that are made up of any combination of ages and sexes. Both males and females will sometimes travel alone. Chimpanzees, like humans, have complex social relationships and spend a large amount of time grooming each other. Grooming is an important way in which alliances are built. Chimpanzee society shows considerable male dominance. Interestingly, male aggression has an important function in establishing a social hierarchy. However, aggression is often only displayed rather than followed through with violence. Males maintain and improve their social position by forming coalitions. These coalitions increase their influence, giving them power that they would not be able to gain alone. Social hierarchies among adult females tend to be weaker. Nevertheless, the status of an adult female may be important for her offspring. Chimpanzees have been described as highly territorial and have been known to kill other chimps for territorial dominance, although there is some suggestion that highly aggressive behaviour by chimpanzees happens only when artificial feeding occurs. A female may mate with several males, though a dominant male may stop other males gaining access to the female with whom they are consorting. Infanticide (the killing of babies) has been recorded among chimpanzees. This is often carried out by male coalitions that invade an existing group, expel their dominant males and kill their offspring: the new males do so in order to mate with the same females and have their own offspring. Care for the young is provided mostly by their mothers. As with humans, babies are dependent on care from an adult for a substantial period. Mothers provide their young with food, warmth and protection and teach them certain skills. In addition, a chimp’s future rank may be dependent on its mother’s status. For their first year, chimpanzees cling to their mothers. By the time they are six, adolescents continue to spend time with their mothers. Like humans, chimpanzees use their highly expressive faces, postures and sounds to communicate with each other. There are many different sounds which signify specific meanings, such as danger, excitement and anger. (Matthew Hoelscher / Wikimedia Commons) Common chimpanzees, living in tropical forests of Africa, live in small communities. These typically range from 20 to more than 150 members; however, chimpanzees spend most of their time travelling in small, temporary groups consisting of a few individuals that are made up of any combination of ages and sexes. Both males and females will sometimes travel alone. Chimpanzees, like humans, have complex social relationships and spend a large amount of time grooming each other. Grooming is an important way in which alliances are built. Chimpanzee society shows considerable male dominance. Interestingly, male aggression has an important function in establishing a social hierarchy. However, aggression is often only displayed rather than followed through with violence. Males maintain and improve their social position by forming coalitions. These coalitions increase their influence, giving them power that they would not be able to gain alone. Social hierarchies among adult females tend to be weaker. Nevertheless, the status of an adult female may be important for her offspring. Chimpanzees have been described as highly territorial and have been known to kill other chimps for territorial dominance, although there is some suggestion that highly aggressive behaviour by chimpanzees happens only when artificial feeding occurs. A female may mate with several males, though a dominant male may stop other males gaining access to the female with whom they are consorting. Infanticide (the killing of babies) has been recorded among chimpanzees. This is often carried out by male coalitions that invade an existing group, expel their dominant males and kill their offspring: the new males do so in order to mate with the same females and have their own offspring. Care for the young is provided mostly by their mothers. As with humans, babies are dependent on care from an adult for a substantial period. Mothers provide their young with food, warmth and protection and teach them certain skills. In addition, a chimp’s future rank may be dependent on its mother’s status. For their first year, chimpanzees cling to their mothers. By the time they are six, adolescents continue to spend time with their mothers. Like humans, chimpanzees use their highly expressive faces, postures and sounds to communicate with each other. There are many different sounds which signify specific meanings, such as danger, excitement and anger. |

Читать дальше

(© LaggedOnUser / Flickr) Bonobos, found living in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have been noted for their sociability. Groups of bonobos range from about 50 to 100 individuals; however, these groups do break up during the day to form foraging parties. Every night bonobos make a sleeping nest from branches and leaves, usually nesting with the smaller group they have travelled with. Bonobo societies are female-centred in structure. Interestingly, like humans, bonobos have sex for purposes other than reproduction. They often manage and resolve social conflicts through sex, making aggression less common than with chimpanzees. In fact, sex is a very important part of the social relations of bonobos. They engage in both homosexual and heterosexual relations, although incest is generally avoided. Sexual interactions occur more often among bonobos than among other primates. Despite the frequency of sex, their rate of reproduction in the wild is about the same as that of the chimpanzee. Bonobo communities have ranges that overlap with other groups. Males are protective of other members of their group and carry out any hunting. Males typically remain among their family group while females range further afield. While males show aggression towards each other, conflict rarely escalates into acts of physical violence. In spite of physical superiority, evidence suggests that males are not aggressive towards females. Bonobos are social animals, and food sharing occurs between males and females, unlike the situation with chimpanzees. Also the female–female relationship is much stronger in this species than it is for chimpanzees. Although they seem very lively, bonobos, like humans, control their emotions when expressing themselves in times of happiness, sorrow, excitement or anger. They are very animated and perform similar gestures to humans when communicating without using language. For example, they will beg by stretching out an open hand or foot and will make a whimpering sound if they fail at something. Females become sexually mature after about twelve years of age and may give birth soon thereafter. They have babies at five- to six-year intervals, so population growth can never be rapid. As with humans, there is a relatively long period of socialization for the young. Females nurse and carry their babies for five years, and the offspring reach adolescence by the age of seven. Females have between five and six offspring in a lifetime.

(© LaggedOnUser / Flickr) Bonobos, found living in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have been noted for their sociability. Groups of bonobos range from about 50 to 100 individuals; however, these groups do break up during the day to form foraging parties. Every night bonobos make a sleeping nest from branches and leaves, usually nesting with the smaller group they have travelled with. Bonobo societies are female-centred in structure. Interestingly, like humans, bonobos have sex for purposes other than reproduction. They often manage and resolve social conflicts through sex, making aggression less common than with chimpanzees. In fact, sex is a very important part of the social relations of bonobos. They engage in both homosexual and heterosexual relations, although incest is generally avoided. Sexual interactions occur more often among bonobos than among other primates. Despite the frequency of sex, their rate of reproduction in the wild is about the same as that of the chimpanzee. Bonobo communities have ranges that overlap with other groups. Males are protective of other members of their group and carry out any hunting. Males typically remain among their family group while females range further afield. While males show aggression towards each other, conflict rarely escalates into acts of physical violence. In spite of physical superiority, evidence suggests that males are not aggressive towards females. Bonobos are social animals, and food sharing occurs between males and females, unlike the situation with chimpanzees. Also the female–female relationship is much stronger in this species than it is for chimpanzees. Although they seem very lively, bonobos, like humans, control their emotions when expressing themselves in times of happiness, sorrow, excitement or anger. They are very animated and perform similar gestures to humans when communicating without using language. For example, they will beg by stretching out an open hand or foot and will make a whimpering sound if they fail at something. Females become sexually mature after about twelve years of age and may give birth soon thereafter. They have babies at five- to six-year intervals, so population growth can never be rapid. As with humans, there is a relatively long period of socialization for the young. Females nurse and carry their babies for five years, and the offspring reach adolescence by the age of seven. Females have between five and six offspring in a lifetime.