These oral traditionswere in flux, as they were sung and told from year to year amidst constantly cycling generations. At one time scholars used to think that nonliterate cultures, such as the early Israelites, had unusual powers of memory that allowed them to memorize and precisely recite oral traditions over hundreds of years. Careful study of such cultures, however, has revealed that people who memorize traditions through purely oral means change those traditions constantly and substantially. To be sure, some elements may be preserved because they are anchored in a name, topographical feature, or ongoing cultural practice. Nevertheless, the singers of oral cultures regularly adapt the traditions they receive – telling versions of the same story about different figures and/or in different settings, revising what those figures say, conforming the story over time to certain broader types of tales (e.g. adding trickster themes), etc.

This means that the early traditions of ancient Israel, whatever they were, evolved in their journey across the centuries of the late second and early first millennia, passing from one set of lips to another. A name such as “Moses” might stick, even the name of a long-abandoned Egyptian city – “Rameses” – but the story of the Israelites’ exodus out of Egypt would evolve as they faced new enemies and challenges in later centuries. In the process of oral telling and retelling, the “Moses” of the story might start to resemble leaders or liberators at the time of retelling, and the “Egypt” of the retold story might resemble later enemies. Similarly, the story of Jacob wrestling God at the Jabbok (now in Gen 32:22–32) explains the place name “Penuel,” and because the place name implies a divine encounter (Penuel is interpreted as Hebrew for “face of God”), that part of the story may have stayed stable over time while other details changed in the retelling process.

MORE ON METHOD: TRADITION HISTORY AND TRANSMISSION HISTORY

Though traditions can be written as well as oral, many scholars use the term “ tradition history” to refer to the history of oral traditions that existed before and alongside the written texts now in the Bible. Different versions of an oral tradition can be recognized by the combination of thematic or plot parallels on the one hand and variation in characters, setting, and especially wording on the other. Take the example of the parallel stories of Abraham and Sarah at Philistine Gerar with King Abimelech (Gen 20:1–18, 21:22–34) and Isaac and Rebekah at the same place and with the same king (Gen 26:6–33). Look at the similarities and differences! Though the two sets of stories are remarkably parallel, they diverge enough from each other that many believe them to be oral variants of the same tales. The same is likely true of different versions of the story of Hagar in the wilderness (Gen 16:1–14, 21:8–19) or three different versions of stories where a patriarch (whether Abraham or Isaac) endangers his wife in the process of trying to protect himself (Gen 12:10–20, 20:1–18, 26:6–11).

The more you compare these texts with each other, the more you should realize just how fluid oral tradition really is. This means we need to move away from concepts of verbatim repetition of traditions and toward a focus on the complex process of transmission (including revision) of traditions, both oral and written! Scholars often use the term “ transmission history” to refer more broadly to the history of the transmission of oral and written biblical traditions. Later in this Introduction we will discuss numerous examples of the growth of written texts through the combination or expansion of earlier sources.

One characteristic appears to have been remarkably frequent, particularly in Israel’s early traditions: the trickster– that is, a character whose ability to survive through trickery and even lawbreaking is celebrated in religion, literature, or another part of culture. As we will see below, the Bible features both male and female versions of such characters, such as the figure of Jacob in Genesis, along with his mother, Rebecca, and his second wife, Rachel. Anthropologists have long noted that many cultures, particularly cultures of more vulnerable groups, celebrate such tricksters who survive against difficult odds through cunning and sometimes deceptive behavior. Figures such as the Plains Indian Coyote demonstrate to their people how one can survive in a hostile environment where the rules are stacked against you. Throughout time people in vulnerable circumstances have celebrated such tricksters, who are often heroes within their own group. In home rituals, agricultural celebrations, weddings and other rites of passage, and other events, they would tell and sing stories of how their ancestors had triumphed against all odds, often tricking and defeating their more powerful opponents. Oral stories about figures like Jacob, Rebecca, and Rachel may have served similar functions in early Israel.

Problems in Reconstructing Early Israel

EXERCISE

EXERCISE

Read Joshua 11. What impression do you get from this chapter of the Israelites’ military accomplishments? How does this compare with the picture of these as summarized in Judges 1? As indicated in the above discussion of “History and the Books of Joshua and Judges”, both these narratives about Israel’s origins were written centuries after the events they describe and are historically problematic.

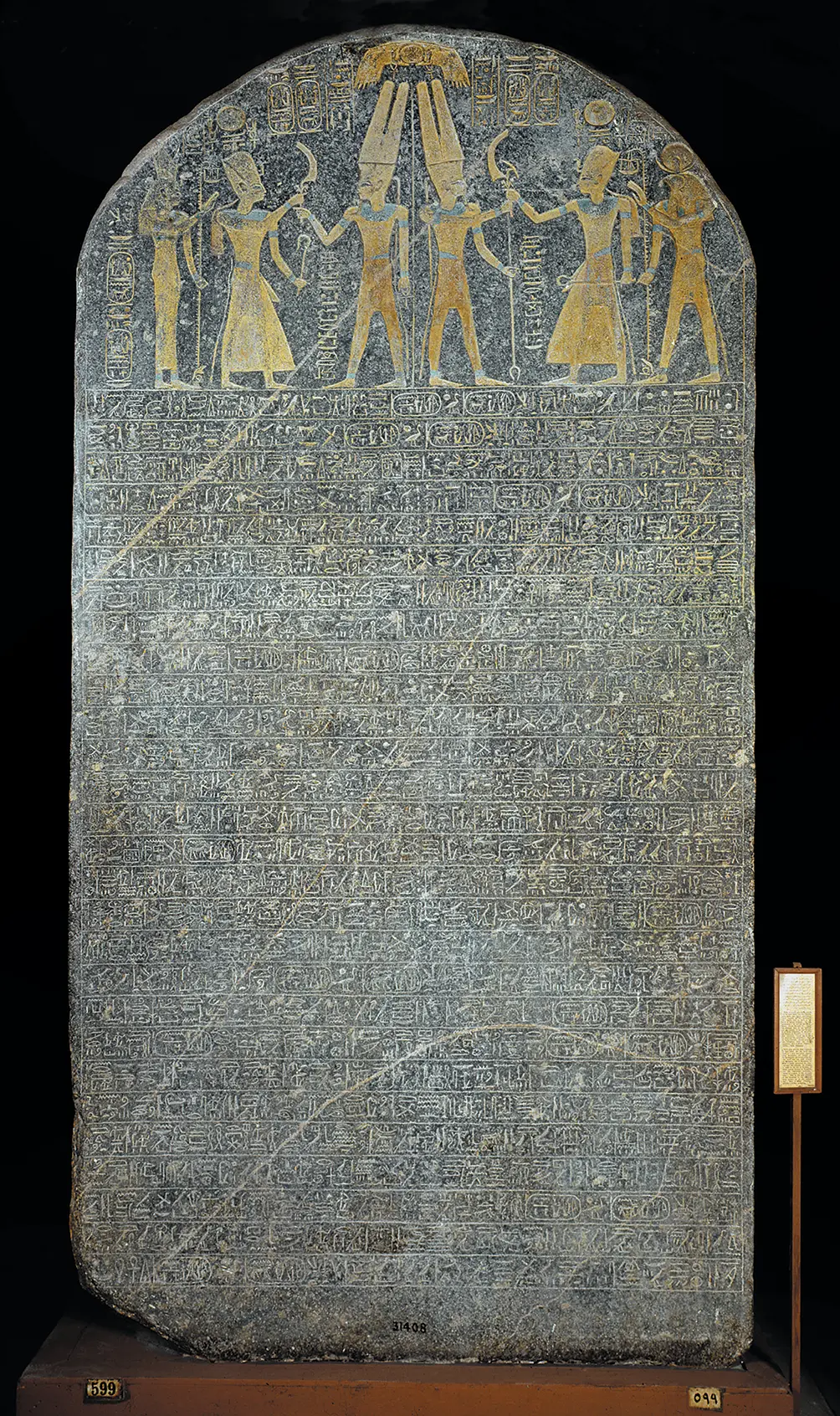

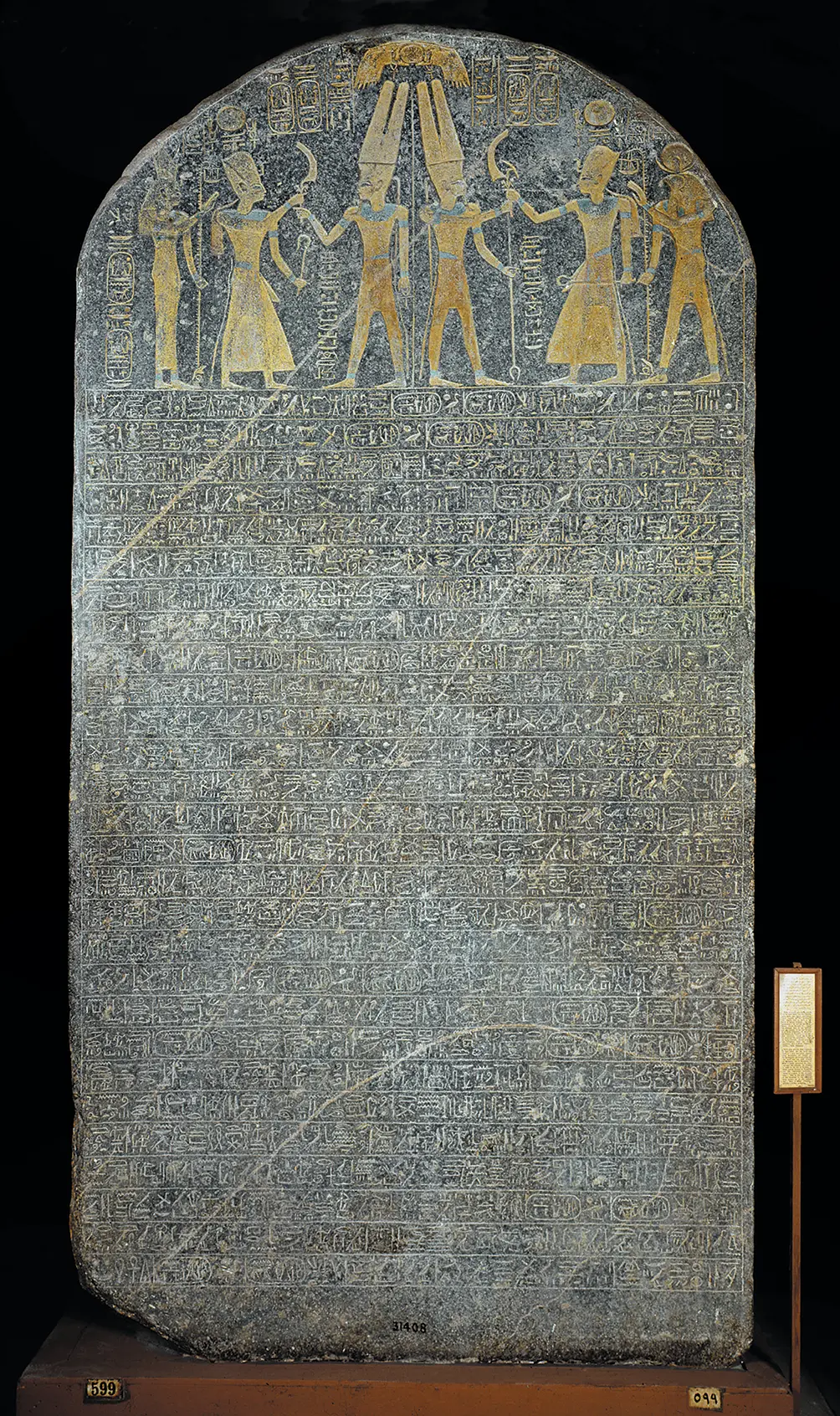

The village imagined above is forever lost for us, if it ever existed in anything like that form. At the most we have fragments of its existence. Archaeological surveys have uncovered the remains of hundreds of settlements in the northern hill country of Israel that suddenly sprang up in unusual numbers around 1250 BCE. Strikingly, this also happens to be around the time when we see the first mention of the name “Israel” in a datable ancient document. A stone monument set up by Pharaoh Merneptah (see Figure 2.4) celebrates his army’s victory over cities and other groups in Syria-Palestine, saying:

FIGURE 2.4 Merneptah stela, including a list of Egyptian conquests and dating to around 1200 BCE. It contains the earliest mention of “Israel” outside the Bible.

Canaan is plundered, Ashkelon is carried off, and Gezer is captured. Yenoam [a town near the sea of Galilee] is made into non-existence; Israel is wasted, its seed [offspring] is no more; and Hurru [a term for Syria] has become a widow because of Egypt.(Translation adapted from that by James Hoffmeier in Hallo, Context of Scripture, vol. 2, p. 41)

The stela commemorates an Egyptian campaign carried out sometime around 1220 BCE. Interestingly, the Egyptian writing system clearly indicates that this “Israel” is a tribal people, not a territory. The next securely datable mention of anything specifically Israelite comes four hundred years later. So this mention of a people, “Israel,” in the Merneptah stela of 1207 is a precious clue. It helps us interpret the village settlements across the hill country in 1250–1000 BCE as the earliest remains of “Israel,” the people who would later create the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament.

The earlier history of this people cannot be recovered. This is as far back as we can go using academic methods of historical reconstruction. Through a combination of archaeological evidence for early hilltop villages and the Merneptah stela, we have good reason to think that some kind of village culture “Israel” already lived in the hill country of Palestine from around 1300 onward (see Map 2.1). Nevertheless, we do not have the kind of secure written or other sources that historians would typically rely on to tell us where these people came from or how they got there.

Читать дальше

EXERCISE

EXERCISE