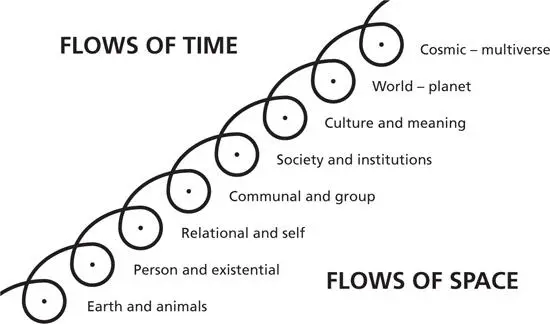

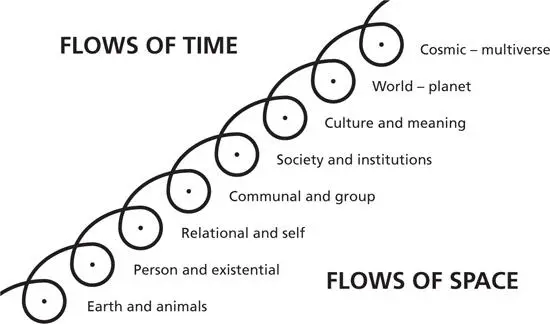

8 Cosmic. And finally, we are a planetary animal connected to the cosmic universe or multiverse. We are a lunar, cosmic animal. A hallmark of our being human in the world is that we look up to the heavens and down to the oceans and can see our insignificance in the vastness of the cosmic order. Excitingly, in many ways hard to fathom, we are connected with this vastness of planetary things. These days, with the help of satellites, we can just click on Google Maps to see and sense our close interconnectedness.

Figure 1.1: The connective spiral of humanity

There is more than all this. Very significantly, we become, each one of us, a uniquely different human being. Remarkable to behold, like all life, the billions of us are each distinctly different from one another and connect to one another in uniquely different ways. A distinctively different and unique life story can be told by each and every life. Humans alone develop a personal and heightened self-aware consciousness of these unique differences. This can become the basis for tensions as well as conflicts. But also surprise and amazement. Consider your own life: even as it remains enmeshed in connections, nobody can ever live a life quite like you. Ever.

Living in Connection and Complexity

Taking our spiralling human connections seriously is no easy task, especially in a digital age. Critical humanism sees ‘connection’ as a pragmatic tool for living life. ‘Humanity’ here becomes the narrative that binds us together through our habitats and pursuits, from the bio-organic to the cosmic. It is through our stories of collective living that we come to sense our togetherness with others, our creativities, our limits. It is through these stories that we can come to sense possible human coherence. We start to see things that might just hold us all together: maybe a common humanity, a solidarity of common projects. Once we start making these narrative connections, we recognize something about who we are, where we came from and, indeed, why we are. All this is at the core of learning about becoming human. Religion is often at the heart of this storytelling. But in the twenty-first century we need more: a wider literacy and pedagogy of hope. New ideas appear across the generations. And older ideas that have recently been heavily critiqued and become unfashionable – like progress, dignity, rights, universal values – can be brought back, reconsidered and reconnected. The world is not a closed place, but a perpetual series of challenges to ‘only connect’. It will be wise to return to humanity and humanism. But this time round, we must do all this with a cautious, careful and critical eye.

1 1 Anne Phillips, The Politics of the Human (Cambridge University Press, 2015). For a recent analysis, see Daniel Chernilo, Debating Humanity: Towards a Philosophical Sociology (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

2 2 Marcus Morgan, Pragmatic Humanism: On the Nature and Value of Sociological Knowledge (Routledge, 2016), ch. 2. Morgan also enumerates some seven responses to this recurrent death of man/humanity/humanism.

3 3 See John Dewey, ‘What Humanism Means to Me’, in Jo Ann Boydston (ed.), John Dewey: The Later Works, 1925–1953, Volume 5: 1929–1939 (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), p. xxxi.

4 4 See Lawrence Grossberg, Cultural Studies in the Future Tense (Duke University Press, 2010), p. 20ff.

5 5 William Du Bois and R. Dean Wright provide an overview of the development in the USA in ‘What is Humanistic Sociology?’, The American Sociologist, 33/4 (Winter 2002): 5–36. In its earliest days it was associated especially with Florian Znaniecki, Charles Cooley, Margaret Mead, Jane Addams and Charles Wright Mills.

6 6 Identified mainly with some of the Frankfurt School intellectuals, such as Erich Fromm, Erik Erikson and even Theodor Adorno in some of his work. See for example, Kieran Durkin, The Radical Humanism of Erich Fromm (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

7 7 See Introduction, note 4.

8 8 Louis Menand provides an outstanding history of early pragmatism in The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America (HarperCollins, 2001). He discusses, among others, Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, Jane Addams and John Dewey. Of the later pragmatists, see Sidney Hook, Pragmatism and the Tragic Sense of Life (Basic Books, 1975).

9 9 Alfred McClung Lee, Sociology for Whom? (Oxford University Press, 1978), pp. 44–5.

10 10 See Edward W. Said, Orientalism (Penguin, 2003 [1978]), p. xx; see also Said, Humanism and Democratic Criticism (Palgrave, 2004).

11 11 More recently, sociologist Daniel Chernilo, in Debating Humanity: Towards a Philosophical Sociology (Cambridge University Press, 2017), has approached the problem another way. With a careful scrutiny of major theorists from just one particular discipline (sociology), he shows how humanist ideas – like responsibility (Hans Jonas), reflexivity (Margaret Archer) and language (Jürgen Habermas) – develop in their work. Here, a multiplicity of key words for humanity could be traced back to such discussions.

12 12 Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism and Progress (Allen Lane, 2018).

13 13 See Pankaj Mishra, ‘Grand Illusion’, New York Review of Books, 19 November 2020, pp. 31–2.

14 14 A small sampling of this work, which I draw on here, includes: Raewyn Connell, Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science (Polity, 2007); Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide (Paradigm, 2014) and The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South (Duke University Press, 2018); Bernd Reiter, Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge (Duke University Press, 2018); Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser, A World of Many Worlds (Duke University Press, 2018); Arturo Escobar, Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible (Duke University Press, 2020).

15 15 See de Sousa Santos, Epistemologies of the South, p. 164.

16 16 Bertolt Brecht, Life of Galileo, trans. John Willett (Methuen, 1986), p. 108.

17 17 For some of this debate, see Hans Joas and Klaus Wiegandt, eds, Secularization and the World Religions (Liverpool University Press, 2009); Peter L. Berger, ed., The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religions and World Politics (Eeerdmans, 1999).

18 18 Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Black Swan, 2006); Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape (Free Press, 2010); Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (Atlantic Books, 2007).

19 19 The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism, ed. Andrew Copson and A. C. Grayling (2015), brings together more than twenty contributors. There is a wonderful opening essay, which outlines many main features of humanism today. It is also made very clear that the anti-religious definition is the real definition of humanism. Stephen Law’s Humanism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2010) also takes this view. See also Philip Kitcher, Life After Faith: The Case for Secular Humanism (Yale University Press, 2014).

20 20 Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Vintage, 2011), p. 465.

21 21 See Brian Cox and Andrew Cohen, Wonders of the Universe (HarperCollins, 2011), p. 241.

22 22 See John Gray’s Seven Types of Atheism (Allen Lane, 2018). With a long history he suggests that secular humanism is only one version of atheism and the least substantial.

23 23 See Phil Zuckerman, Society Without God: What the Least Religious Nations Can Tell Us about Contentment (New York University Press, 2008).

Читать дальше