For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available:

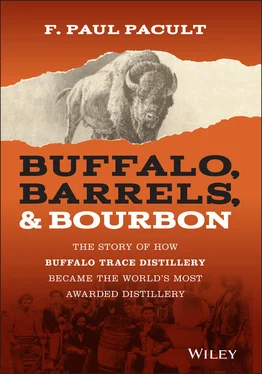

ISBN 9781119599913 (Hardback)

ISBN 9781119599937 (ePDF)

ISBN 9781119599920 (ePub)

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Images: © Buffalo Trace Distillery

Author Photo: © Michael Gold/The Corporate Image

For Sue

I HAVE A WHOLE scorecard of generous people to thank for their assistance with the writing of this book. First of all, Matt Holt, the former Wiley publisher who approached Sue and me about writing a third book for Wiley, along with our present-day Wiley publisher Shannon Vargo. I appreciate their staunch support of Buffalo, Barrels, & Bourbon . Senior Editor Sally Baker and Managing Editor Deborah Schindlar at Wiley have been veritable rocks and a delight to deal with. Kudos also go to my friend Sarah Tirone for poring over the manuscript at a critical stage of development and telling, with candor, what she thought of it. Whiskey journalist/blogger/author Chuck Cowdery freely offered his keen insights along the way, both in person and via his many unvarnished blog postings. Thank you, Chuck. My appreciation also goes to colleague and celebrated whiskey writer Liza Weisstuch for her insightful viewpoints. Both the Filson Historical Society and the Kentucky Historical Society deserve a tip of my hat for their very existence, as well as the assistance their archives provided throughout the book's research period. Never standing in the way of where my independent research was leading me, the management and public relations teams at Buffalo Trace deserve shout-outs for their no-strings-attached cooperation, fully cognizant that my findings might in the end differ with their own data. A special note of appreciation goes to Buffalo Trace archivist Madison Sevilla, whose patience and diligence were pivotal in pointing out directions for deeper research. I would be remiss if I didn't note and acknowledge American whiskey historian Carolyn Brooks for sharing her superb investigative paper, “A Leestown Chronology,” which cleared many obstacles and bridged gaps on my fact-finding path. Last, but certainly not least, thanks to my wife, collaborator, master editor, and partner Sue Woodley for, well, everything.

MY PROFESSION IS COMMUNING with spirits. Since 1989, I have formally reviewed over 30,000 of the fermented and distilled consumable liquids commonly referred to as “spirits,” “distillates,” “water of life,” or, more scurrilously, “firewater,” “hooch,” “booze,” “sauce,” or “hard liquor.” In addition to my subscription-only newsletter F. Paul Pacult's Spirit Journal , these product evaluations, sometimes with accompanying feature stories, have appeared in scores of publications over the past three decades. These included the New York Times Sunday magazine , Wine Enthusiast, Playboy, Delta Sky in-flight magazine , Wine & Spirits, Men's Journal, Beverage Dynamics , Cheers, and many more. Wearing another of my career hats, for two decades I have consulted to numerous beverage companies, assisting them either in the creation of new spirit brands or helping them to revitalize old ones. In one such instance, I have turned master blender for an American whiskey portfolio, Jacob's Pardon. Then there is my spirits education hat, but on this I'll spare you details, saving them for the next time.

After plying my trade in this manner for over 30 years, I have come to many conclusions. Perhaps the most salient determination I have made is this: of all the spirits that illuminate the galaxy of distilled potables, whiskey is my hands-down favorite. As charming as it can be, whiskey is a perplexing spirits category, one that is on occasion disconcerting and, at its most extreme, impenetrable. Yet for all its manifold complexities, every whiskey is composed of only three easily obtained, foundational ingredients: grain, water, and yeast. After being fermented and distilled, freshly made whiskeys are placed in cocoon-like barrels wherein they undergo periods of complicated metamorphosis. Once released from captivity in the aging warehouses, the world's whiskeys take the international stage as the most prized and expensive of all distillates. They are the monarch butterflies of the spirits category. They can be, and frequently are, great hooch, in other words.

One of whiskey's most enduring mysteries is why one can be so wildly dissimilar in character traits from another, not just from nation to nation or region to region, but even from barrel to barrel of the same batch. If all of the world's whiskeys are made from but a trio of commonplace, wholly familiar ingredients, how can they differ so markedly in personality? Moreover, why are a handful of the whiskey distillers more adept at the art of whiskey making than others? What are their secrets? I've been asking these questions for over three decades.

Three years ago, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., the Hoboken, New Jersey–based publisher of two previous books of mine, American Still Life (2003) and A Double Scotch (2005), contacted me, expressing an interest in backing another spirits-oriented business book. The topic choice, they said, was up to me. After some weeks of consideration deciding between proposing another book on Scotch whisky or one more on American whiskey, I settled on a subject that had all the earmarks of timeliness and pertinence: the meteoric rise in prominence of the Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky. Along with a chapter and verse accounting of this distillery's emergence since before the nineteenth century, my other hope was to perhaps answer at least some of my queries about a few of whiskey's inherent riddles.

Wiley agreed to my proposal and the deal was struck. Upon informing the distillery operators about the project, I made arrangements to meet with their archivists to peruse their voluminous records. The top executives at Buffalo Trace at the time, namely CEO Mark Brown, public relations manager Amy Preske, master distiller Harlen Wheatley, master blender Drew Mayville, and former senior marketing director Kris Comstock (who departed early in 2021), have all known me long enough to know that I would allow the facts of the historical records as I unearthed them to dictate the trajectory of the story, warts and all. As with American Still Life and A Double Scotch, my independence would not permit a vanity project. They acknowledged that my views might in the end differ with theirs and to their credit offered me their assistance, encouragement, and direct access to the company archives. Nothing more.

As an active spirits critic, I have grown intimately familiar with the bourbon and rye whiskeys produced in abundance at their historic plant, which is now a celebrated landmark. As the research data unfolded over many months of examination, I became convinced that Buffalo Trace's history deserved to be told as much from the viewpoint of its low-bank location on the Kentucky River as from the intriguing lives of the people who created the legendary bourbon and rye whiskeys through the decades. The striking history of the distillery's site was, in my view, of paramount importance to the proper telling of the story. The tale of Buffalo Trace Distillery, I concluded early on, could not have occurred at any other place.

Читать дальше