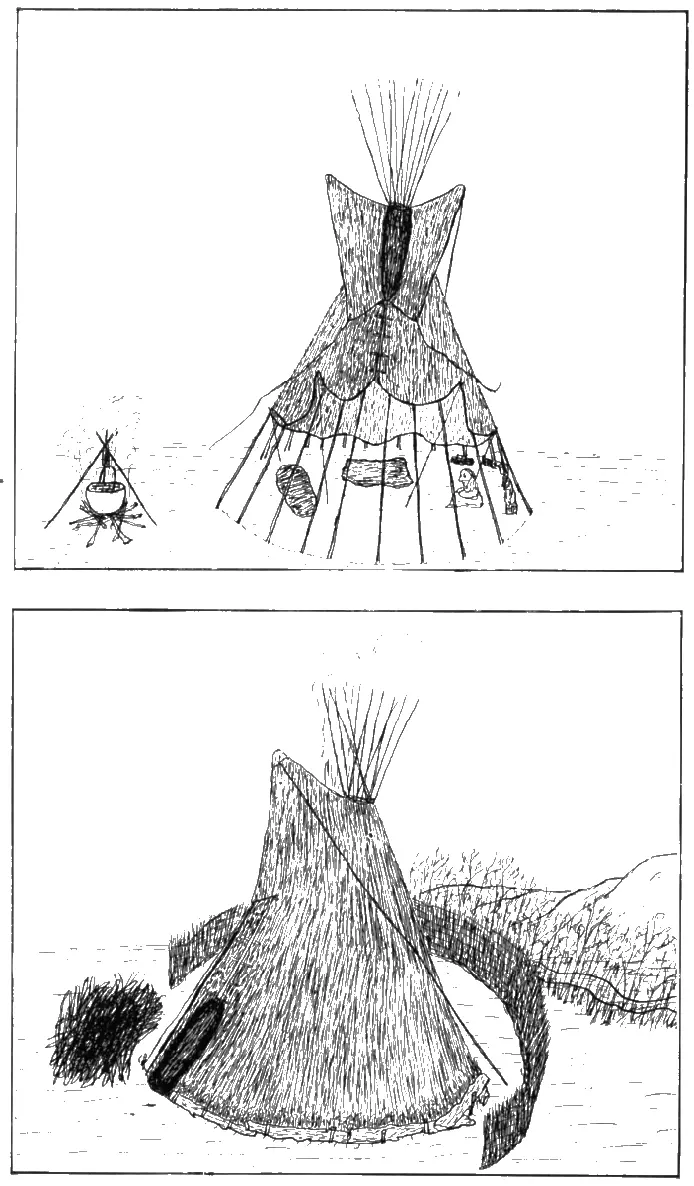

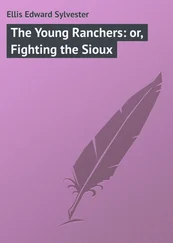

Soon the hot summer days arrived. Perhaps the reader may think we had an awful time in a closed tipi, but not so. Forked branches were cut from the box-elder tree. While this is a very soft wood, at the fork of a branch it is tough. The branches were cut four or five feet long. Sometimes ash was used, but box-elder was better.

The tipi, all around, was staked down with pins. The women would pull all these pins out on hot summer days, which left the tipi loose around the bottom. The forked ends of the box-elder branches were then placed through the holes around the edge of the tipi, which elevated the edge some little distance, quite like an open umbrella. This not only increased the size of the tipi, but made the amount of shade greater. When the tipis were kept nice and clean, it was very pleasant to stroll through a great camp when all the tipi bottoms were raised.

During the heated portion of the day, our parents all sat around in the shade, the women making moccasins, leggins, and other wearing apparel, while the men were engaged in making rawhide ropes for their horses and saddles. Some made hunting arrows, while others made shields and war-bonnets. All this sort of work was done while the inmates of the camp were resting.

We children ran around and played, having all the fun we could. In the cool of the evening, after the meal was over, all the big people sat outside, leaning against the tipis. Sometimes there would be foot races or pony races, or a ball game. There was plenty we could do for entertainment. Perhaps two or three of the young men who had been on the war-path would dress up in their best clothes, fixing up their best horses with Indian perfume, tie eagle feathers to the animals’ tails and on their own foreheads. When they were ‘all set’ to ‘show off,’ they would parade around the camp in front of each tipi—especially where there were pretty girls.

We smaller children sat around and watched them. I recall how I wished that I was big enough so I could ride a perfumed horse, all fixed up, and go to see a pretty girl. But I knew that was impossible until I had been on the war-path, and I was too young for that. Before we could turn our thoughts toward such things, we must first know how to fish, kill game and skin it; how to butcher and bring the meat home; how to handle our horses properly, and be able to go on the war-path.

When the shades of night fell, we went to sleep, unless our parents decided to have a game of night ball. If they did, then we little folks tried to remain awake to watch the fun. We were never told that we must ‘go to bed,’ because we never objected or cried about getting up in the morning. When we grew tired of playing, we went to our nearest relatives and stayed at their tipi for the night, and next morning went home.

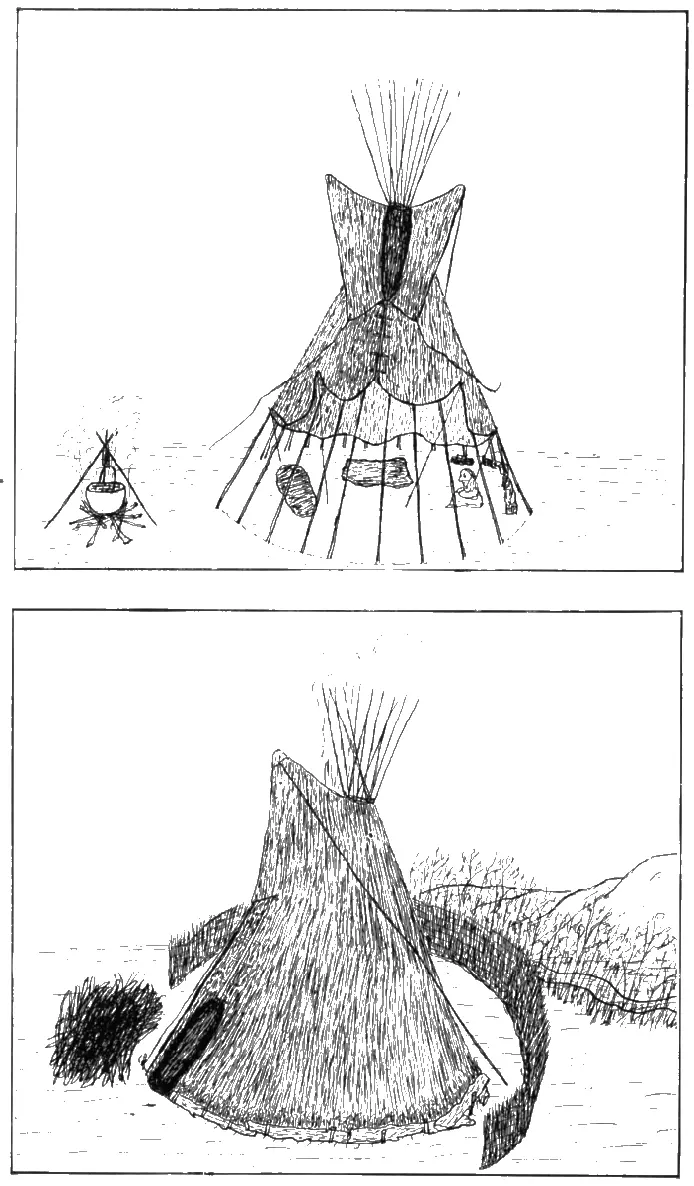

When a thunderstorm threatened, every one ran to his tipi. All the forked branches were pulled out, and the sides of the tipi were lowered. If a high wind accompanied the storm, the women, boys, and girls were all hustling, pounding the stakes into place with stone hammers. Then the long branches from the box-elder tree were carried inside the tipi to be used as braces for the poles, which kept them from breaking in. After the storm had passed, how fresh and cool all the earth seemed!

Such was the life I lived. We had everything provided for us by the Great Spirit above. Is it any wonder that we grew fat with contentment and happiness?

THE TIPI IN SUMMER AND IN WINTER

From drawings by the author

PRAYING TO THE GREAT SPIRIT THROUGH THE PIPE OF PEACE

Posed by Chief Standing Bear

Table of Contents

Now I was beginning to consider myself as a big boy, and naturally did not run to my mother with every little thing. When we children were not playing together, I spent my time looking for game or fishing. One day my mother went to see her mother, who lived some little distance from us. My mother belonged to the Swift Bear band. When night came and she did not return for supper, I did not cry. Some other women came to our tipi, and they were very good to me. My father thought Mother would soon return.

Some days afterward, one of my uncles of the Swift Bear band saw me playing, and beckoned me to come to him. He took me to my mother. What a wonderful feeling it was again to be with my own mother. She combed my hair, gave moccasins to me, and also some nice things to eat. And I was really happy to be petted. She never mentioned to me about going back to my father, and, in fact, never thought of returning.

One day, when I was playing outside, my father called for me. I went home with him, and he gave me a horse and all the things necessary to make a man of me. When I went inside the tipi, the two women were still there, and they both called me ‘son.’

These two women were the two wives of my father. They were sisters. We all lived in the same tipi, and they were both very good to me. But when their own children came, there was a difference.

In this day, such an arrangement would make it very hard for the children, but in my time it made life better for me. There were more relations to look after me. My father’s parents had both passed to the Great Beyond. But my own mother yet had both her parents, and so did my stepmothers. So I had four grandparents, and they were all good to me. It was the duty of the grandmothers of the tribe to look after the children. When my brothers and sisters went over to see their grandmother and I went along, she did not have things as nice for me as for her own daughter’s children.

When I visited my mother’s mother, she made nice things for me, and that made up for what I lost from the others. My own mother had two sisters, and they each had two children. My mother had one daughter before she married my father, and the girl lived with her. I now had two homes—one at my father’s and one with Mother. When I would go to visit Mother, her sister’s children, and my own sister and I would call on my grandmother. We called all ‘brothers and sisters.’ The term ‘cousin’ was not used.

Grandmother had as many bladder skins tanned as there were children. These skins were used in the place of paper bags, and she always kept them clean and put away until we visited her. On such occasions Grandmother would make some ‘wasna’ for us. There was not as much grease added as in that made for the older people. Grandmother would add a little sugar and choke-cherries for us children.

When it was all made, she would fill the little bladder bags and give one to each of us. We ran and played and ate our hash from these bags, as white children of to-day eat candy. After we had emptied the bags, we returned them. We enjoyed our stay, as we had plenty to eat. Grandfather had a big place, and it made him very happy to have all the children with him. He was a very industrious old man. His name was ‘Wo-wa-se,’ or ‘Labor.’ This name really suited him, as he was always busy. Grandfather was a very good man, and he liked my father. So as there was no trouble between my parents, I went back and forth at will.

We were now safely settled for the winter in the Black Hills, and we began to prepare things for our winter games.

When our people killed a buffalo, all of the animal was utilized in some manner; nothing was wasted. The skins were used as covers for our beds; the horns for cups and spoons, and, if any of the horns were left, they were used in our games.

Читать дальше