“I’ll have the police come back for you,” she assured him. “I can’t even imagine how a baby can live here.” She glanced down at the skirt and the top she had on. How Thandi had managed to withstand her brothers’ ludicrous, decrepit ideas was beyond Hannah’s imagination. Mandla had asked her politely not to wear the jeans she had arrived in around his brothers, and she’d obeyed, but what she could endure for a couple of days was quite different from what she would have to condone as a way of life.

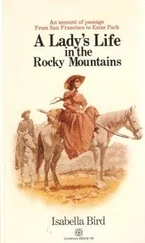

The men didn’t even have a car, as far as she could see. They’d ridden off to town like cowboys, and when she’d asked to accompany them, they’d promised to take her to town as soon as they returned from their important errand. There, they assured her, she could telephone her office. And so, she had waited, and waited.

She and the baby were asleep when the men finally came home. She didn’t hear them coming in until their voices filled the house and the baby began to cry. For a moment she thought she was dreaming, like all the other nights when she had heard a baby crying out for her and had awakened in her empty room alone. This time the baby’s cry continued in the darkness, and she reached over and pulled him from his cradle.

“He said he wasn’t going to kill anyone anymore!” Thabani shouted. “He swore it, Mandla.”

“Keep your voice down,” Mandla reminded him. “I don’t want Miss overhearing any of this.”

“I didn’t mean to kill him, Mandla, honest. The gun just went off …”

“Again? The man can hit a tin from two hundred metres away, but he can’t keep his gun from going off by accident. Mandla, he …”

The room went silent when they noticed Hannah and the baby. She stood in the doorway, her heart pounded. She could not believe what she had heard.

“Go back to your room,” Mandla said. He stared at her, waiting for her to do as she was told.

“Who?” she finally asked, clutching the baby tightly as though one of them might try to take him away.

“You ever hear of the ‘Dlemza’ Gang?” Themba asked, the stupid smile she had seen so many times before lighting up his face.

“Who?”

“Shut up, Themba,” Thabani said. He opened his rifle, and her breath caught in her throat. He began stuffing a rag down one of the barrels.

“I will not,” Themba said. “I’m proud of who I am.”

“Go back to your room,” Mandla repeated, this time more ominously.

“I can’t,” Hannah said, her voice smaller than she would have liked. She sat down with the baby asleep in her arms. Maybe she had misheard. Maybe her ears were full of sleep, her mind still full of dreams. “You’d better tell me everything.”

“You ever hear of Philani Mbuli?” Themba asked, but before she could answer, Mandla was on his feet and in front of her.

“I said go back to your room,” he ordered between clenched teeth. This time he put one hand under her elbow and lifted her out of her seat. “It’s best if you get some rest, we can discuss all this in the morning,” he said, ushering her to her door without her consent.

“Themba is crazy, isn’t he?” Hannah said.

She couldn’t take her eyes off the scar that ran down Mandla’s cheek. It pulsed under her scrutiny.

Mandla shrugged. “Yeah, I guess that’s it,” he said, waiting for her to enter her room. “But you don’t have anything to worry about.” He shut the door behind her.

Hannah laid the baby down in the cradle and paced the room nervously, finally she sat on the rug beside the door with her ear to the floor, hoping to hear anything else that the brothers might reveal. She had some trouble understanding Mandla’s words, his deep voice rattling the floorboards beneath her.

“Great, Themba. Just great. Now Miss will want to leave.”

Themba must have shrugged or said, “So what.” It was Mandla’s voice that Hannah heard again.

“So, who’s going to stay home with Mashwa when we need to go out? Or were you planning to take him? Strap him to your back and jump onto the train, you idiot!”

She could hear the boom of Thabani’s voice, but she couldn’t make out the words over Themba’s footsteps and the jangling of his spurs.

“She wouldn’t find her way back here even if we drew her a map,” Mandla argued.

So, they’d gotten to the heart of the matter. She knew where they were. And if she left, she could lead the authorities back to them. Were they now trying to scare her with this bad guy talk so that she’d leave and forget about Musa? Or had Themba really killed someone? She heard footsteps and quickly dove to her bed. They stopped outside her door, and she heard the doorknob being turned. Through slits in her eyes she saw Mandla’s silhouette fill the doorway.

“Miss?” he whispered.

She didn’t answer.

“I hope you aren’t planning to go anywhere,” he said quietly; watching for a reaction. She gave him none, and he quietly shut the door, leaving her alone in the darkness. Hannah crawled further under the blankets. Suddenly she was very, very cold.

***

“I guess you’re a bit uncomfortable,” the man behind her said, and Hannah craned her neck around to glare at him.

The saddle’s pommel drilled a hole in her hip, and each step the horse took caused her agony. She still couldn’t figure out quite how it had happened. One moment she was down by the river, putting her basket of washing down and reaching in to pick the baby up, ready to make a run for it before Mashwa’s uncles realised that she was gone. The next moment she was tied up like a sack of potatoes and thrown over a neck of a horse, the size of a B-52.

“Look,” the man said, and it was clearly an explanation, not an apology. “I wasn’t planning to take you with me.” She grunted. It was the best she could manage under the circumstances.

“The idea was for me to grab the baby, but when you opened your pretty little mouth and started screaming, I saw that I really didn’t have any choice.”

He shook his head and then shrugged, shooing a fly away from Hannah’s face at the same time. At the mention of the baby, she was all ears. So, it was her little Pat who the man was after, and not her. Well, it was a good thing she screamed, then. And she wasn’t sorry about the biting and the clawing, either. She would never give up that sweet child without a fight. If she was willing to steal him away from his blood relatives, she wasn’t about to turn him over to some Scar faced aspirant.

“Leastwise, I got the baby,” he said, and Hannah wriggled herself around to stare at him through narrowed eyes.

A dirty bushy beard covered most of his face, but through it she could see a row of shiny white teeth. He was smiling, the idiot, as though he didn’t have a care in the world.

So, you belong to one of those Dlamini boys, don’t you? Or were you just watching the baby? not that it matters to me, mind you. I’m just curious.” He spoke in a voice just above a whisper, a soft voice that could calm a squirmy child or a feral animal, but it drove Hannah crazy. How could he be having a normal conversation at a time like this? The man had to be insane.

He went on pleasantly, as if everything was normal.

“Mandla, I think is the only one nearly human, although that might be sweetening it a bit; And he didn’t seem all that cosy with you at the river yesterday. Themba, now, he’s just insane. Been nuts since … well, since always, as I can recall. But I didn’t know that he was insane enough to allow you to go down to the river alone with Thabani. Which brings us to Thabani, who’s just grossly mean? Worse than a grizzly.”

It wasn’t easy for Hannah to have a good look at the man who rode behind her. It was hard for her to get a good look at anything but the stallion’s underbelly, a fancy gun with a jumping dog carved in silver just near the trigger, and the parched road, feeding her nostrils with dust. No place in the country was as dry as Big Bend – Lavumisa Mountains, and when she finally got Musa and returned home, she was going to relax the whole week in a cool tub with one cool drink after another.

Читать дальше