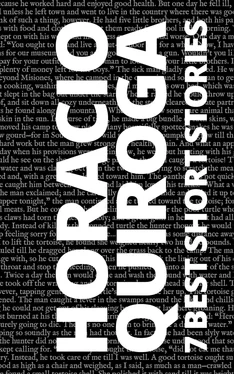

Horacio Silvestre Quiroga Forteza (31 December 1878 – 19 February 1937) was a Uruguayan playwright, poet, and short story writer.

He wrote stories which, in their jungle settings, used the supernatural and the bizarre to show the struggle of man and animal to survive. He also excelled in portraying mental illness and hallucinatory states, a skill he gleaned from Edgar Allan Poe, according to some critics. His influence can be seen in the Latin American magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez and the postmodern surrealism of Julio Cortázar.

Being a follower of the modernist school founded by Rubén Darío and an obsessive reader of Edgar Allan Poe and Guy de Maupassant, Quiroga was attracted to topics covering the most intriguing aspects of nature, often tinged with horror, disease, insanity and human suffering. Many of his stories belong to this movement, embodied in his work Tales of Love, Madness and Death.

Quiroga was also inspired by British writer Rudyard Kipling (The Jungle Book), which is shown in his own Jungle Tales, a delightful exercise in fantasy divided into several stories featuring animals.

His Ten Rules for the Perfect Storyteller, dedicated to young writers, provides certain contradictions with his own work. While the Decalogue touts an economic and precise style, using few adjectives, natural and simple wording, and clarity of expression, in many of his own stories Quiroga did not follow his own principles, using ornate language, with plenty of adjectives and at times ostentatious vocabulary.

As he further developed his particular style, Quiroga evolved into realistic portraits (often anguished and desperate) of the wild nature around him in Misiones: the jungle, the river, wildlife, climate, and terrain make up the scaffolding and scenery in which his characters move, suffer, and often die. Especially in his stories, Quiroga describes the tragedy that haunts the miserable rural workers in the region, the danger and suffering to which they are exposed, and how this existential pain is perpetuated to succeeding generations. He also experimented with many subjects considered taboo in the society of the early twentieth century.

In his first book, Coral Reefs, consisting of 18 poems, 30 pages of poetic prose, and four stories, Quiroga shows his immaturity and adolescent confusion. On the other hand, he shows a glimpse of the modernist style and naturalistic elements that would come to characterize his later work.

His two novels, History of a Troubled Love and Past Love, deal with the same theme that haunted the author in his personal life: love affairs between older men and teenage girls. In the first novel, Quiroga divided the action into three parts. In the first, a nine-year-old girl falls in love with an older man. In the second part, it is eight years later, and the man, who had noticed her affection, begins to woo her. The third part is the present tense of the novel, in which it has been ten years since the young girl left the man. In Past Love history repeats itself: a grown man returns to a place after years of absence and falls for a young woman he had loved as a child.

Knowing the personal history of Quiroga, the two novels feature some autobiographical components. For example, the protagonist in History of a Trouble Love is named Eglé (the name of Quiroga's daughter, whose classmate he later married). Also, in these novels, there is a great deal of emphasis on the opposition of the girls' parents, rejection that Quiroga had accepted as part of his life and that he always had to deal with.

The critics never liked his novels and called his only play, The Slaughtered, "a mistake." They considered his short stories to be his most transcendent works, and some have credited them with stimulating all Latin American short stories after him. This makes sense since Quiroga was the first person to be concerned about the technical aspects of the short story, tirelessly honing his style (for which he always returns to the same subjects) to reach near-perfection in his last works.

Though clearly influenced by modernism, he gradually begins to turn the decadent Uruguayan language to describing the natural surroundings with meticulous precision. But he makes it clear that Nature's relationship with man is always one of conflict. Loss, injury, misery, failures, starvation, death, and animal attacks plague Quiroga's human characters. Nature is hostile, and it almost always wins.

Quiroga's morbid obsession with torment and death is much more easily accepted by the characters than by the reader: in the narrative technique the author uses, he presents players accustomed to risk and danger, playing by clear and specific rules. They know not to make mistakes because the forest is unforgiving, and failure often means death. Nature is blind but fair, and the attacks on the farmer or fisherman (a swarm of angry bees, an alligator, a bloodsucking parasite, etc.) are simply obstacles in a horrible game in which Man tries to snatch property or natural resources (reflecting Quiroga's efforts to do so in life), and Nature absolutely refuses to let go, an unequal struggle that usually ends with the human loss, dementia, death, or simply disappointment.

Sensitive, excitable, given to impossible love, thwarted in his commercial enterprises but still highly creative, Quiroga waded through his tragic life and suffered through nature to construct, with the eyes of a careful observer, narrative work that critics considered "autobiographical poetry". Perhaps it is this "internal realism" or the "organic" nature of his writing that created the irresistible draw that Quiroga continues to have on readers.

Ten Rules for the Perfect Storyteller

BY HORACIO QUIROGA

1.- Believe in a master – Poe, Maupassant, Kipling, Chekov – as in God himself.

2.- Believe that your art is an unreachable summit. Don’t dream of reaching it. Once you can reach it, you will without even knowing you’ve done it.

3.- Resist imitation if possible; but if the urge is too great, imitate. More than anything, developing a personal voice takes a lot of time and patience.

4.- Have blind faith in your capacity to succeed, or in your desire to achieve success. Love your art like your girlfriend, giving it all your heart.

5.- Don’t begin to write without knowing where you are going from the first word. In a good short story, the first three lines are almost as important as the last three.

6.- If you want to express “a cold wind blew from the river,” write just that. Once you have mastered the use of words, don’t worry whether they are consonant or assonant.

7.- Don’t add unnecessary adjectives. Colorful words attached to a weak noun will be useless. The correct noun will have incomparable color and brightness. The trick is finding it.

8.- Take your characters by the hand and lead them firmly to the end, ignoring everything but the way you have plotted. Don’t get distracted by seeing things that they cannot and care not to see. Don’t abuse your reader. A short story is not a miniature novel. Hold this as an absolute truth, even though it isn’t.

9.- Do not write from under the power of your emotions. Let the feeling die and evoke it later. If you are able to conjure up the feeling again, you are halfway to mastering your art.

10.- Don’t think about your friends when you write or on the effect that your story may have. Tell your story as if it only mattered to the confined world of your characters, of which you may be a part. This is the only way to give your story life.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Читать дальше

![Коллектив авторов - Best Short Stories [С англо-русским словарем]](/books/26635/kollektiv-avtorov-best-short-stories-s-anglo-thumb.webp)