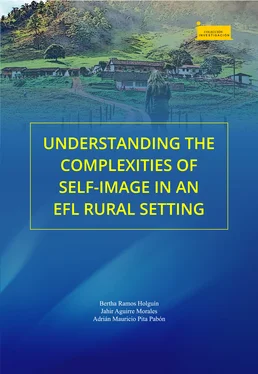

In Colombia, rural areas often lack opportunities in all aspects of life, including education. Children who have the opportunity to graduate from high school are faced with the reality of a limited job market. For some graduates, working in the countryside with their father and older brothers is their only option, while women must help at home and raise families at a young age. Nevertheless, farm and housework are physically exhausting and not well paid, which is why we continue to see that 70% of the rural population is under the poverty line (Ramos & Aguirre, 2016).

Given the situation, we wanted to explore eleventh graders’ self-image and understand how they build their image and how it informs about their imagined life after high school.

The Colombian high school educational system finishes at eleventh grade. Talking with eleventh graders in rural areas has revealed that they are full of energy and dreams. Some want to continue studying and go to college to move up the socio-economic ladder. Others want to pursue their dreams and shape their lives. While others are aware of the limited economic resources that will ultimately affect their decisions. Without a doubt, eleventh graders in rural areas are faced with many challenges that will determine their future, which is why understanding their self-image was crucial for us.

In this book, we looked at self-image from a humanistic approach. We see it as a dynamic and complex process that compromises self-respect and self-confidence. As a complex process, self-image is influenced by the community in which the individual interacts (school, neighborhood, home, etc.). All in all, self-image is a continuous process that begins from childhood (Rijavec, 1997; Bognar, 1999; Yahaya & Ramli, 2009; Simel, 2013). Furthermore, a positive self-image can generate many benefits. Heatherton and Wagner (2011) mentioned that having a high self-esteem helps people cope with cognitive and social challenges to live a better life.

We were also aware of the fact that the protagonists of this story were adolescents, who are in search of their selves and identities as human beings. As narrators of the story, we wanted to explore, analyze, and interpret how these adolescents perceived their self-image through their life stories. By telling their narratives, the students could reconstruct and re-signify their reality, while showing us who they are in relation to other people and their contexts. Therefore, life stories offered us the possibility to explore students’ inner and social worlds.

In order to explore the adolescents’ self-image, we needed to understand their life stories as a thoughtful practice as opposed to a technical one. Doing so helped us increase our sensitivity to how the adolescents saw themselves as part of their rural contexts, as well as how this might affect their futures. In addition to understanding the students’ self-image, we also wanted to make sure this book echoed their voices. Therefore, we will be sharing the stories of a group of eleventh graders from a high school in Samacá, one of the 123 towns in the state of Boyacá, Colombia. The students come from a rural area since this is largely an agricultural state.

This book is divided into five chapters that describe a journey. In this trip we made some stops. In the first chapter, The Trip that we Planned, we narrate where and how this trip began. We contextualize the reader with our understanding of rurality as well as with the initial concerns of the research group.

In the second chapter, Our Fellows in this Trip, we present the authors who theoretically support our concerns. We discuss the concepts of self-image and its connection with life-stories. All these within the framework of the rural specificities in Colombia.

In the third chapter, Our Rest Area to Reflect upon in this Trip, we present the protagonists and the context in which this qualitative research study was carried out. We introduce the reader with the social subjects and their life-stories. We also illustrate the rural context that shaped those stories. We describe narrative inquiry as a method to rely on to comprehend self-image construction.

In the fourth chapter, The Experiences we Encounter in our Journey, we describe, interpret, and comprehend what the self-stories reveal about eleventh-graders self-image. Finally, in the last chapter, The Photo Album we End Up with in this Voyage, we summarized the findings and we open the window for future comprehension in regards to EFL rural teaching and learning processes in Colombia.

THE TRIP THAT WE PLANNED

The research group TONGUE has had a history of working with rural areas and education communities. We have been able to witness the dire need to comprehend rural education and how it shapes people’s experiences. We have also come to understand that the school is no longer a place to teach subjects. It has become an opportunity for students’ voices to be amplified and echoed. Because of this, we recognize that education also encompasses a humanistic orientation to it. As such, we agree with Bognar (1999), who suggests that the humanistic perspective is still neglected and suppressed in our schools in particular with the education of a positive self-image.

We considered the previous argument and our experiences with eleventh graders at a public institution in Boyacá, Colombia, to make the choice to understand their self-images. We wanted to comprehend how the students, who are constantly constructing and co-constructing their self- image and identity, went through the process. As researchers, we used this opportunity to get to know them, and their contexts better. Since the idea of self-image implies taking a look at how people and the community see themselves, the students’ life stories would allow us to take a deeper look at what lied beneath their words as their underwent the process of self-image construction.

In addition to the previous, one of our main objectives, as teachers-researchers, was to gain a better understanding of our teaching practices by getting to know our students’ complex realities in a rural school. We did so by asking our students to write their life stories, which helped them express themselves, how they saw their world, and what they lived every day. The life stories gave us a glimpse into their world, which would have been invisible if we had focused primarily on EFL teaching and learning.

As teachers, we understand all too well assigning students multiple written pages focused on grammar, spelling, punctuation, and structures. However, we have come to realize that these assignments rarely provide the chance to contemplate meaning. Instead, it is tempting to judge students’ writing based on their lack of spelling or grammatical disfunction. Similarly, we have also been guilty of giving students writing topics that restrict their freedom to express themselves. As we grow in our teaching practices and think about our students, we chose to focus on short life stories that could give students the freedom to write meaningful narratives about themselves, their lives, and how they saw themselves within their communities. Their stories went far beyond the linguistic features of the language. Moreover, they invited us to share, comprehend, and open our minds to their lives.

We wanted our students to see the language as a vehicle to express themselves and for their voices to be heard as part of their local community. Part of our point of view comes from the idea that schools play an important role in a students’ self-image construction. According to Simel (2013), schools need to create a positive environment, so that individuals can create an idea of themselves in a safe place. Additionally, schools and society go hand-in-hand when it comes to change, which means that schools have to provide a space where students’ characteristics are discovered, valued, and highlighted. Simel (2013) also pointed out that it is difficult to witness students’ personal growth within a traditional classroom, where the teacher is the center of the class. To witness the students’ perspectives; a student-centered approach needs to be the core of the learning process.

Читать дальше