Julius Firmicus confirmed Ptolemy and enlarged upon his observations. The subsequent discovery of the planets Uranus and Neptune by Herschel and Adams, widened the field of research and gave to later astrologers the clue to much that hitherto had been imperfectly understood. Not that these discoveries overturned the whole system of astrology, as some have imagined and foolishly stated, or that they negatived the conclusions drawn from the observed effects of the seven anciently known bodies of the solar system, but it became possible after a lapse of time to fill in the blank spaces and to account for certain events which had not been traced to the action of any of the already known planets. The discovery of argon did not destroy our conclusions regarding the nature and characteristics of oxygen or hydrogen or nitrogen, nor give an entirely new meaning to the word “atmosphere.” If even so many as seven new planets should be discovered, there would yet not be a single paragraph of this book which would need revising. What is known regarding planetary action in human life is known with great certainty, and the effects of one planet can never be confounded with those of another. Incomplete as it must needs be, it is yet a veritable science both as to its principles and practice. It claims for itself a place among the sciences for the sole reason that it is capable of mathematical demonstration, and deals only with the observed positions and motions of the heavenly bodies; and the man who holds to the principia of Newton, the solidarity of the solar system, the interaction of the planetary bodies and their consequent electrostatic effects upon the Earth, cannot, while subject to the air he breathes, deny the foundation principles of astrology. The application of these principles to the facts of everyday life is solely a matter of prolonged research and tabulation upon an elaborate scale which has been going on for thousands of years in all parts of the world, so that all the reader has to do is to make his own horoscope and put the science to the test of true or false. The present writer is in a position to know that the study of astrology at the present day is no less sincere than widely spread, but few care to let their studies be known, for, as Prof. F. Max Müller recently said, “So great is the ignorance which confounds a science requiring the highest education, with that of the ordinary gipsy fortune-teller.” That to which the great Kepler was compelled “by his unfailing experience of the course of events in harmony with the changes taking place in the heavens,” to subscribe “an unwilling belief,” the science which was practised and advocated by Tycho Brahe under all assaults of fortune and adverse opinion, the art that arrested the attention of the young Newton and set him pondering upon the problems of force and matter, which fascinated the minds of such men as Francis Bacon, Archbishop Usher, Haley, Sir George Witchell, Flamstead, and a host of others, is to-day the favourite theme of thousands of intelligent minds and bids fair to become a subject of popular inquiry.

It is believed that the present work will be of considerable assistance to those who seriously contemplate an initial study of the science of horoscopy, and although it by no means exhausts what is known on the subject, yet it will be found accurate and reliable as far as it goes, and will enable any one of ordinary intelligence to test the claims of Astrology for himself. This is as much as can be expected in the limits of a small handbook. The literature of the subject is considerable, and the present writer only takes credit to himself so far as his own wide experience and practice have enabled him to present the subject in a simple and brief manner.

SECTION I

THE ALPHABET OF THE HEAVENS

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I

THE PLANETS, THEIR NATURES AND TYPES

Table of Contents

The luminaries and planets are known to astronomers under the following names and symbols:—

The Sun ☉, Moon ☽, Neptune ♆, Uranus ♅, Saturn ♄, Jupiter ♃, Mars ♂, Venus ♀, and Mercury ☿.

Neptune revolves around the Sun in its distant orbit once in about 165 years. Uranus completes its orbital revolution in 84 years, Jupiter in 12 years, Mars in about 15 months, Venus in 11 months, and Mercury in 18 weeks. If you imagine these bodies to be revolving in a plane around the Sun and yourself to be standing within the Sun, the motions of these bodies will appear almost uniform and always in one direction. Were the orbits of the planets circular and the Sun holding the centre of the circle, their motions would be constant, that is to say, always in the same direction and at the same rate. But the orbits are elliptical, and the Sun holds a position in one of the foci of each ellipse. Consequently the planets are at times further from the Sun than at others, and they are then said to be in their aphelion, the opposite point of the orbit where they are nearest to the Sun being called the perihelion. When at aphelion the planets move slower, and when at perihelion they move quicker than at the mean distance. Astronomers employ an imaginary circular orbit for the planets, in which they move at an uniform rate of velocity, which is called the mean motion. This is subject to an equation depending on the position of the planet in its orbit, and it determines the difference between the imaginary planet and the true planet. The equation itself depends on the eccentricity of the orbit, that is to say, its relation to a circle drawn around the same focal centre. The Earth follows the same laws as all other bodies of the same system.

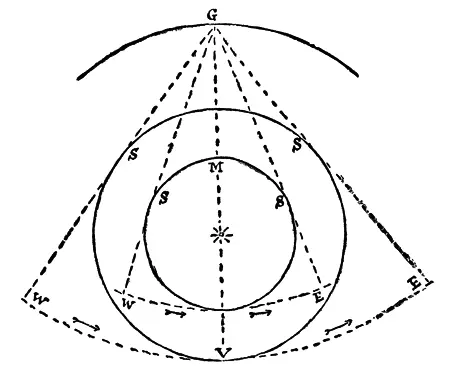

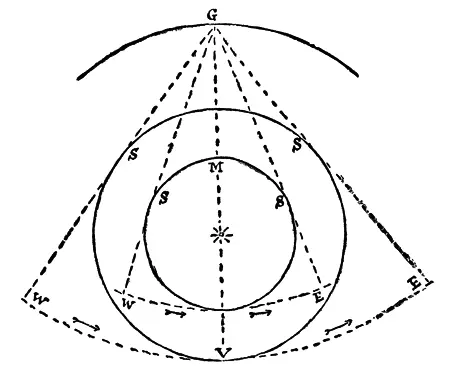

But if we imagine the Earth to be stationary in space and the centre around which the planets revolve, their motions present several irregularities. Mercury and Venus will then appear to revolve around the Sun while the Sun revolves around the Earth, sometimes being between the Earth and the Sun, which is called an Inferior conjunction, sometimes on the further side of the Sun away from the Earth, as at their Superior conjunction; and again, at other times to the right or left of the Sun, in East or West elongation. The other planets, having orbits greater than that of the Earth, will appear to revolve around it at constantly varying distances and velocities. At certain points in their orbits they will appear to remain stationary in the same part of the Zodiac. The annexed illustration will assist the lay reader perhaps. The body M is Mercury when at Inferior conjunction with the Sun, as seen from the Earth. The letter V is the planet Venus at Superior conjunction with the Sun. The points W and E are the points of greatest elongation West and East, and the letter S shows the points in the orbit at which those bodies appear to be stationary when viewed from the Earth, at G. As seen from the Earth, Venus would appear to be direct and Mercury retrograde.

Astrologically we regard the Earth as the passive subject of planetary influence, and we have therefore to regard it as the centre of the field of activity. If we were making a horoscope for an inhabitant of the planet Mars, we should make Mars the centre of the system. The planets’ positions are therefore taken as from the centre of the Earth (Geocentric), and not as from the centre of the Sun (Heliocentric). An astrological Ephemeris of the planets’ motions is employed for this purpose (see Sect. II., chap, i.), and there are 480,000 of these sold to astrologers or students of astrology every year, from which fact it is possible to draw one’s own conclusions as to the state of Astrology in the West. These figures, of course, do not include the millions of almanac readers nor the Oriental students, who prepare their own ephemerides.

Читать дальше