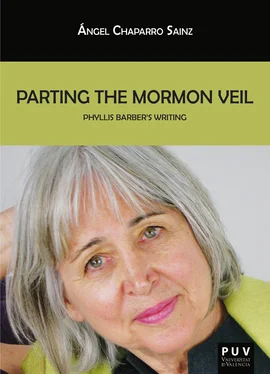

Phyllis Barber

INTRODUCTION

Beyond the Edges

We both needed time

and perspective.

Phyllis Barber, Raw Edges

I got involved with Mormon literature by accident. Without going into detail let me say that “by accident” I mean that there was no specific reason or objective at the beginning. In fact, at first, I approached this topic with a certain degree of prejudice. Take into account my situation: Phyllis Barber—the object of my research—is a Mormon 1woman, raised in Las Vegas, who studied music and eventually became a professional pianist. I, on the other hand, am not a religious person, nor am I a woman. I had never been to Nevada before I began my research, nor do I play the piano or even enjoy classical music. Even though I seem to have very little in common with the object of my research, I considered myself sensitive enough and adequately prepared to undertake this challenging task.

I also feel equipped to write an accurate book about a body of literature that represents a contemporary exercise on motley connections and disconnections. This conviction emerged from my reading of Barber’s books and articles, and my study of many other writers who work under the label of Mormon literature. This introduction consists of a general explanation of how I faced the challenge to approach Mormon literature, and how I designed a book to show that Phyllis Barber’s literature provides a powerful approximation to a particular and complex culture. But before I do so, there is one more task to tackle: I need to explain the source and magnitude of the label “Mormon literature.” It would be wise to assume that not everybody knows that Mormon literature exists. The fact that I cannot take for granted that everyone knows about the existence of Mormon literature justifies my initial motivation for writing this book. In response to this, I have included two introductions to the history of the Mormon community and to Mormon literature that stand as a prelude to my analysis of Phyllis Barber’s literature. Be that as it may, I find it necessary to also here provide a brief introduction to the literary context in which I place my analysis so that the theme gets clarified from the very beginning.

It was only forty years ago that scholars and critics began to talk about Mormon literature. The first college classes on this subject were held in the late 1970s, and the first anthology, A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints (1974) was published in the same decade. Although we are now in the 21 stcentury, Mormon literary criticism is still in the process of being shaped and formed: passionate discussions about the purpose of Mormon literary criticism and the limits and concerns of both the criticism and the literature still take place among Mormon scholars and writers.

Many scholars today address the development of a critical framework for Mormon literature. Within this framework, the label Mormon literature must be defined. Nevertheless, Mormon literature has been isolated or ignored by college programs over the past two hundred years. Almost no trace of, or reference to, Mormon literature can be found in the literature programs of universities, not counting those that are located in those geographical areas where The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has established communities. The attention given to Mormon literature is even scarcer in Europe. Michael Austin—a Mormon scholar who champions a place for Mormon literature in the literary history of Western American literature and Minority Studies—laments in his article “How to Be a Mormo-American; Or, the Function of Mormon Literary Criticism at the Present Time” that “there are only a handful of non-Mormon scholars outside of the Rocky Mountain West who even know that there is such a thing as ‘Mormon literature’” ( How 1). Austin argues that today, when programs from different universities focus on diversity and minorities in order to widen the concept of literature and expand the canon, Mormons deserve a proper place within Western American literature. John-Charles Duffy, in his detailed compilation of Mormon scholarly influence in non-Mormon universities, concludes that since the 1990s most of the scholarly work under way in universities of non-Mormon affiliation has been directed along the lines of the orthodox approach or what he calls “faithful scholarship” (Duffy, Faithful 2). Duffy links faithful scholarship to orthodoxy, meaning by orthodox that it “is overtly predicated on orthodox LDS belief, notably the objective, empirical, historical reality of LDS claims about the Book of Mormon being an ancient record miraculously translated by Joseph Smith from golden plates” (Duffy, Faithful 2), although he notes that the lines are blurred and the distinctions are not so sharp.

In conclusion, a need is still prevalent in academia for the incorporation of these authors, topics and perspectives that it is usually unable to accommodate. Levi S. Peterson pinpoints one of the possible reasons for mainstream academia’s hesitation regarding Mormon literature: “Mormonism is one of the most aggressive religions in the world, and it is getting bigger and bigger. You cannot give a fair reading to literature that you think in its deepest intent aims to subvert your spiritual bearings” (Bigelow 133). Whether or not this explains the lack of support for Mormon literature in the international realm, the truth is that Mormon literature has multiple ramifications that expound its contemporary manifold nature.

It is less than two hundred years since Joseph Smith founded the Church and yet, in this brief amount of time Mormons have established a specific identity that has generated a significant body of literature. In the forty years since Mormon literature began to emerge many Mormon literature enthusiasts have tried to write good fiction, whether strictly Mormon or not. Mormon literature relies on a bond that has nothing to do with geographical coincidences. In some cases, Mormon literature is defined on the basis of spiritual matters, which makes it more complex. In the last two centuries, a number of Mormon writers have come to merit critical analyses and reached major visibility. Writers such as Clinton F. Larson, Vardis Fisher, Virginia Sorensen, Maurine Whipple, Darrell Spencer, Carol Lynn Pearson, Terry Tempest Williams, Levi S. Peterson, Linda Sillitoe, Orson Scott Card, Brady Udall and Phyllis Barber have all raised questions about Mormonism and about literature. The works of some of these authors transcend the limits of their Mormon identity, becoming rooted instead in personal and unique experiences of the American West. They are essentially American and Western, but the international expansion of the Church 2is opening wider horizons: horizons that many of those writers have already reached. Their books have leapt over oceans, they have crossed borders, they have mastered languages and they have drawn connections that have exhausted the meaning of labels.

From all those names that I just mentioned, it was Phyllis Barber’s works that I first came to know, and it happened by accident. Barber herself might have said that some kind of veil 3parted for me then, implying that it is not an “accident” that I came to be involved in this project. And she would be right in a way. I first came to know Barber’s work because she is a widely known, prize-winning writer. She earned a relevant place in Western American literature with How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir (1992). Thirteen years later, she was included in the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame for her contribution to the publicity of the state of Nevada. Still, she has not yet received the international exposure that some other Mormon writers enjoy, but a retrospective overview of her literary production discloses a potential contribution to the growing range of variety and complexity that makes up Western American literature.

Читать дальше