Contrary to French, the Spanish language was introduced gradually and through a longer period of history considering that Melilla fell under the Spanish protectorate as early as 1497. Nevertheless, Spanish could hardly interfere in the linguistic and cultural scene of Morocco. More importantly, the use of the Spanish language never went beyond the northern part of Morocco and the Moroccan Sahara and it never penetrated in the educational or administrative domains as French did. As is the case with French, Spanish today is also learned as a foreign language at the secondary school level.

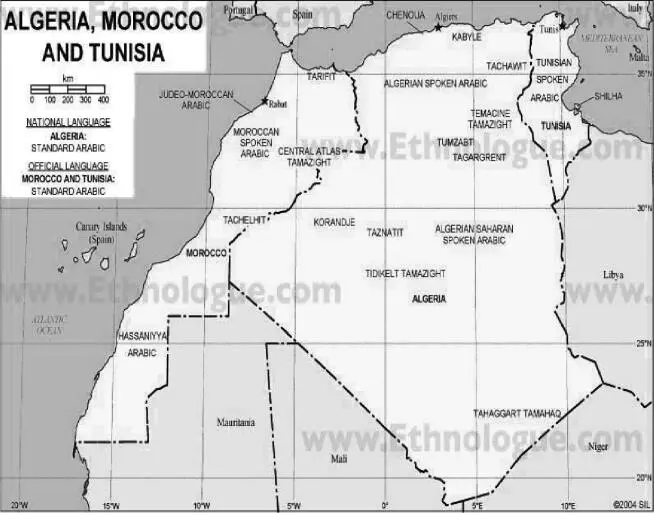

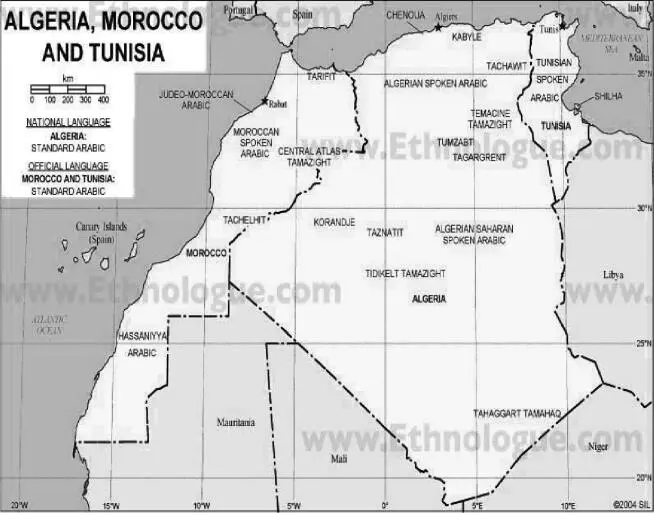

Within this complicated sociolinguistic panorama, Berber has survived all these invasions and re-invasions taking refuge in the mountains as if waiting for a better social climate to reappear. For decades, Berber was neglected as a language and Berbers were considered Moroccans of “second type”. To speak Berber was synonymous with under-civilization. As an approximation to the linguistic persecution that Berber has experienced as a language and as a culture, we find the case of “Valenciano” in Valencia the capital city of Comunidad Valenciana where those who speak Valenciano were identified as “gent de poble” (in Valenciano) as a pejorative denomination. Similar to this sociolinguistic infra-evaluation we find in MA the appellative “3robi” used by Arabic speaking Moroccans to Berbers to denote a lack of civism and culture. However, if we consider the etymology of the word “3robi” I think that the word “3robi” is a corruption of “3arabi” CA meaning someone who speaks Arabic as a pejorative appellative to those who speak Arabic at a time when Berber was the dominant language in Morocco and Arabic was the language of the “invader”. It might also be a corruption of the word “A3rabi” from CA also meaning “country man”. Even the word “Berber” is pejorative in itself, or at least this is how it could be understood granting that Berbers never refer to themselves as Berbers but as “Imazighen” the plural of “Amazigh” who speaks “Tamazight” i.e.: the Berber language. Tamazight is classified as belonging to the Afro-asiatic branch and descending from the Proto-Afro-Asiatic language. From a linguistic migration theory, and as claimed by historical linguists, Berber is believed to have existed in Eastern Africa 12.000 years ago. However, Berbers today are located principally in Northern Africa and the language represents an estimated population of 36 million Berber speakers distributed in countries all over the world. The most representative country in terms of the density of the Berber population is Morocco (18.980.000) then Algeria (12.800.000). Then, to a lesser degree, Niger (1000.000); also Mali (700.000); Libya (280.000); Mauritania (150.000); Tunisia (130.000); Israel /100.000); and Egypt (20.000).

***

After this brief historical overview of the function and the status of the languages that exist in Morocco, we will be concerned in the following paragraph with MA and its varieties and accents. MA is rated as low (L) in a diaglossic relation with Modern Standard Arabic, usually considered as high (H) (Ferguson, 1976). However, MA is the mother tongue of Moroccans and it is the most practical and the only means of communication used by most Moroccans 4 . MA is known in Morocco as “Darija” and it has no written form. It is exclusively used as a spoken language. MA shares many properties with the CA to put it as Gravel (1979) and Bentahila (1983) claim, MA and CA exhibit many variations as far as phonology, syntax and morphology are concerned. Despite the historical relation of MA and CA, the origin of MA and the other similar “low” languages spoken in Morocco and in every Arab country in parallel with CA, was a matter of controversy for many linguists. Consequently, three different theories were founded to delimit the origin of these low varieties. The first one situates these varieties as derived from CA and representing a linguistic continuum of CA. The second theory views these varieties as pertaining to a spoken language, which existed side-by-side with the formal and the written CA (Ferguson, 1976). The different Arabic “dialects” which are in use in the different Arab countries 5 are referred to as “Arabic Koiné”. Finally, the third theory states that these low varieties have developed from different Koinés.

From a contrastive point of view, MA exhibits many variations in comparison with CA in the areas of lexis, syntax and phonology. CA phonemes like /ð/, /  / and /θ/ are actually realized as /d/, /ḍ/ and /t/ and as far as lexis is concerned, the lexical repertoire of MA is marked by an exaggerated borrowing from French, Spanish and Berber. In some cases, we find instances where some borrowed words no longer serve the same meaning as in the language they are borrowed from. On the syntactic level, however, MA seems to have a more simplified system of inflection in comparison with CA. This fact endows MA with more freedom in what concerns word order. MA is also void of duality and the feminine plural and case endings are distorted. In terms of tense, the time of the action is not clearly segmented as in English or French (Meziani, 1985: 190). On the contrary, in MA the action is projected as fulfilled or not fulfilled, that is, any action performed at a specific point is an action done in the past of that point, or, contrariwise, any action not completed is considered present. Mainly, accomplished actions are marked by forms used as prefixes of the verb as, for example, /ghadi/ which is used to announce futurity and /rah/ to describe an action in progress. As Meziani (1985: 190) claims: “The MA verb has in and of itself no reference to the temporal relations of the S (speaker). It is concerned rather with the realization of a process or event.” Consequently, in MA speakers have recourse to periphrastic forms, i.e.: adverbs of time, to refer to a specific time.

/ and /θ/ are actually realized as /d/, /ḍ/ and /t/ and as far as lexis is concerned, the lexical repertoire of MA is marked by an exaggerated borrowing from French, Spanish and Berber. In some cases, we find instances where some borrowed words no longer serve the same meaning as in the language they are borrowed from. On the syntactic level, however, MA seems to have a more simplified system of inflection in comparison with CA. This fact endows MA with more freedom in what concerns word order. MA is also void of duality and the feminine plural and case endings are distorted. In terms of tense, the time of the action is not clearly segmented as in English or French (Meziani, 1985: 190). On the contrary, in MA the action is projected as fulfilled or not fulfilled, that is, any action performed at a specific point is an action done in the past of that point, or, contrariwise, any action not completed is considered present. Mainly, accomplished actions are marked by forms used as prefixes of the verb as, for example, /ghadi/ which is used to announce futurity and /rah/ to describe an action in progress. As Meziani (1985: 190) claims: “The MA verb has in and of itself no reference to the temporal relations of the S (speaker). It is concerned rather with the realization of a process or event.” Consequently, in MA speakers have recourse to periphrastic forms, i.e.: adverbs of time, to refer to a specific time.

Apparently, MA is identified and defined as the language spoken by all Moroccans, but the geo-linguistic reality is different. Ennaji (1985) and Gravel (1979) stated that MA is composed of five regional dialects, which have common syntax and morphology but with their own distinctive features.

Font: Gordon, Raymond G. (2005).

Starting from the North, we find the Tanji dialect, which is spoken in Tangier. Though it takes its name from Tangier, this dialect is also spoken in Tetouan and Larache. Due to the geographical proximity and the recent history of Spanish colonialism, this dialect is characterized by the integration and use of many Spanish lexical items. Considering the phonological level, Gravel (1979: 91) notes that the Tanji phonological inventory includes a large number of diphthongs. In the north east of Morocco and up to the Morocco-Algerian border, the dialect spoken is Oujdi, namely from Oujda. This dialect is characterized by its similarity to Algerian Arabic rather than to MA as a result of the immediate contact with Algerians and possibly due to the settlement in this area of Algerians who escaped from the war with France in the sixties. In the western and the central parts of Morocco, the dialect spoken is “Casablancais” which is not only found in Casablanca but also in the surrounding rural areas of this city. The most salient feature of this variety is the insertion of the pronoun /tta/ just before any imperative to give more emphasis to the petition (Gravel, 1979: 90). However, this practice is not common among all “Casablancais” but rather among some uneducated people. In the area of Fès and Rabat we find the Fassi and Rbati dialects respectively. These dialects, as is the case with the Tanji dialect, show a phonological alteration as to the pronunciation of the phoneme /g/ which is realized as /q/ or in some other instances as /?/. Another phonological particularity about the Fassi dialect is the realization of /r/ as a velar instead of an apical flapped sound. Turning to the south of Morocco, we find the Marrakshi dialect, as a linguistic variety spoken not only in Marrakesh, but rather in all the neighbouring areas of this city. The Marrakshi dialect is characterized by the realization of /g/ instead of /q/ which we find in Fassi and Tanji dialects and in CA; or /?/ also found in the mentioned dialects as well as in the Egyptian dialect. Another distinctive phonological aspect of the Marrakshi dialect is the dropping of the velar sound /ġ/ exclusively in the word “bgha” , which is pronounced as /ba/.

Читать дальше

/ and /θ/ are actually realized as /d/, /ḍ/ and /t/ and as far as lexis is concerned, the lexical repertoire of MA is marked by an exaggerated borrowing from French, Spanish and Berber. In some cases, we find instances where some borrowed words no longer serve the same meaning as in the language they are borrowed from. On the syntactic level, however, MA seems to have a more simplified system of inflection in comparison with CA. This fact endows MA with more freedom in what concerns word order. MA is also void of duality and the feminine plural and case endings are distorted. In terms of tense, the time of the action is not clearly segmented as in English or French (Meziani, 1985: 190). On the contrary, in MA the action is projected as fulfilled or not fulfilled, that is, any action performed at a specific point is an action done in the past of that point, or, contrariwise, any action not completed is considered present. Mainly, accomplished actions are marked by forms used as prefixes of the verb as, for example, /ghadi/ which is used to announce futurity and /rah/ to describe an action in progress. As Meziani (1985: 190) claims: “The MA verb has in and of itself no reference to the temporal relations of the S (speaker). It is concerned rather with the realization of a process or event.” Consequently, in MA speakers have recourse to periphrastic forms, i.e.: adverbs of time, to refer to a specific time.

/ and /θ/ are actually realized as /d/, /ḍ/ and /t/ and as far as lexis is concerned, the lexical repertoire of MA is marked by an exaggerated borrowing from French, Spanish and Berber. In some cases, we find instances where some borrowed words no longer serve the same meaning as in the language they are borrowed from. On the syntactic level, however, MA seems to have a more simplified system of inflection in comparison with CA. This fact endows MA with more freedom in what concerns word order. MA is also void of duality and the feminine plural and case endings are distorted. In terms of tense, the time of the action is not clearly segmented as in English or French (Meziani, 1985: 190). On the contrary, in MA the action is projected as fulfilled or not fulfilled, that is, any action performed at a specific point is an action done in the past of that point, or, contrariwise, any action not completed is considered present. Mainly, accomplished actions are marked by forms used as prefixes of the verb as, for example, /ghadi/ which is used to announce futurity and /rah/ to describe an action in progress. As Meziani (1985: 190) claims: “The MA verb has in and of itself no reference to the temporal relations of the S (speaker). It is concerned rather with the realization of a process or event.” Consequently, in MA speakers have recourse to periphrastic forms, i.e.: adverbs of time, to refer to a specific time.