A related topic that seems to receive different treatments depending on the culture is sex. While one the Spanish magazines selected, Super Pop , includes two enquiries dealing with sex (8S and 10S) and provides answers which denote a tolerant attitude towards this issue, some American magazines tend to avoid it: “the social nature of adolescent problems surrounding sexuality is avoided” (Currie 2001: 272). Thus, whereas sex may be a ‘naturalized’ concern for female adolescents in the Spanish culture, it may not be the case in other cultures, adopting a more conservative stance. In fact, one of the cases in Super Pop deals with the correct use of a contraceptive method to avoid unwanted pregnancy (i.e. “Preservativos fiables”), contrary to what seems to happen in American teenzines: “Also conspicuously absent is the reassurance that the problem of unwanted pregnancy is shared by others, and that questions about birth control and contraception are ‘common’” (Currie 2001: 273-274), despite the fact that female adolescents turn to teen magazines for information about sex (Medley-Rath 2007: 25). Can we conclude that sexual desire in female adolescents is naturalized in the Spanish culture? Two isolated examples cannot be extrapolated to make such generalization, but I dare say the open treatment given to the topic of sex in the Spanish magazine Super Pop is an index of equalization of women in a domain that was before exclusively naturalized for men, as Currie (2001: 274) states.

On the other hand, there are certain topics, which may be considered relevant for teenager’s education and general formation, that are absent in these publications, such as discussion of political issues, personal development through intellectual pursuits, sports, or women’s independent professional development. In fact, an advice column in a different section of Girls’ Life called “Best of: Advice” addresses the issue of getting a job (“Snag that job: Dos and Don’ts”), but the sort of advice provided exclusively focuses on superficial, or even frivolous, issues, such as physical appearance (“look cute when you fill your application”), the body language the applicant should use when talking with the potential employer (“Don’t look at the floor when you’re talking”), even if it is on the phone (“Smile big on the phone when you’re talking to your future boss”), or the external support the applicant may have (“Bring phone numbers of people you know who can give you a good reference”). As can be observed, there is no promotion of the intellectual or professional assets needed for a given job. That way of addressing this issue favours a sexist view of the employee, who has to gain a job mainly by her physical appearance, rather than thanks to her professional qualifications.

In the following section, the second part of the adjacency pairs, the writers’ answers to girls’ enquiries, is analysed in order to observe the linguistic devices used together with their pragmatic meaning.

5.1.2. Answers (2nd pair-parts): the use of directives

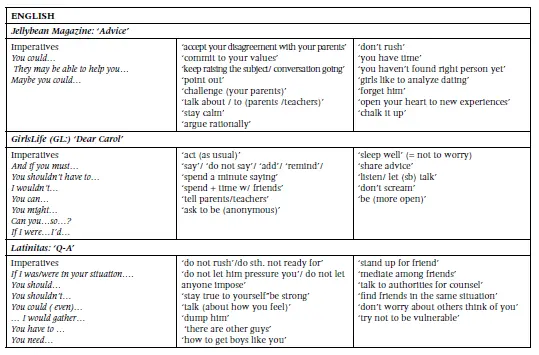

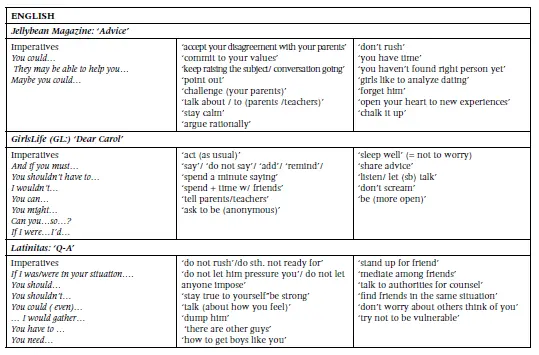

In what follows the linguistic coding in which magazine writers construct their advice is analyzed (i.e. how they phrase their directives). Table 2 displays the different types of directives found in each of the magazines studied, both in English and in Spanish. The first column displays the linguistic forms and the second one provides a gloss of the message content (i.e. what form of behaviour was suggested). This latter is a gloss of the message being sent, rather than the actual words, in order to reveal generalizations among answers regarding the type of advice provided.

As far as form is concerned, Table 2 shows that imperatives are present in all publications. It is, in fact, the most prevalent form, with no reddressive action, what Brown and Levinson (1987) term bald-on-record . However, taking into consideration that the advice provided has been requested by the reader herself, the degree of imposition of the directive is low. Furthermore, imperatives do not seem to be mandatives (Tsui 1994), since they actually function as advice given for the reader’s own sake; that is, they are, in Tsui’s (1994) terms, advisives . Despite this, directives are phrased at times with other expressions which do contain mitigating devices. In Spanish, a confirming question tag is used at the end of an imperative sentence to soften the degree of imposition of an example of prohibition: “Nada de ponerse a mirar la tele y eso, ¿eh?” [No TV watching and things like that, OK?]. On the other hand, when unsure of the advice provided, some softening devices are used in several examples in English: “The one thing we can probably deduce with some certainty is that this guy did like you, at least for a while” or “ Maybe he found a new girl to crash on … or he could even have a girlfriend now ”.

When having a closer look at directives, it can be observed that they actually fulfil different sub-functions depending on their degree of imposition. Here are some examples from English and Spanish, classified according to their sub-function; the structure used to phrase de directive is also mentioned in square brackets:

a) Commanding. When contrasting both languages in the examples below, it can be observed that, in the case of commanding, both English and Spanish use imperatives, but neither of them sounds threatening, since the actions commanded are beneficial for the reader:

(1) “Habla con un adulto y explícale la situación” (Speak with an adult and explain the situation to him/her, Bravo ) [Imperatives]. (2) “Take your time, really get to know him well, and push yourself to keep things innocent until you feel that you no longer can” ( Jellybean ) [Imperatives].

b) Advising. Advising is very similar to commanding (at times, difficult to distinguish). The use of imperatives is seen in both English and Spanish and the action benefits the addressee (it may actually be interpreted as an emergency to help her, as exclamation marks seem to indicate in Spanish):

(3) “¡Rodéate de gente que realmente te quiera!” (Surround yourself with people who truly love you, Bravo ) [Imperative]. (4) “So my advice to you is, don’t move past friends with this guy if it feels like rushing” ( Jellybean ) [Imperative + conditional clause]

Furthermore, there are certain social circumstances where using a direct command is considered appropriate among social equals (Yule 1996: 64). As I will argue in the following section, the discourse that writers use in teenzines establishes a good rapport with their readers, which makes them, apparently, equals. And I say ‘apparently’ because they are not actually so, since the writer, by suggesting the form of action, is actually the one in power, even if not felt as such by the reader. Even in the case of Latinitas , where readers and advisers are of the same age, the adviser exerts (subliminal) power on the advisee controlling the latter’s behaviour.

c) Suggesting. When suggesting, writers use, in both languages, mitigating devices: the modal verb poder (‘can’) in Spanish and the verbal periphrasis try to + verb in English, which presupposes that the reader may not commit the action suggested:

Читать дальше