18. When you retire to the bedroom, prepare the bed as soon as possible, taking into account that, although female hygene is crucially important, your husband will not want to wait in order to use the bathroom [Cuando os retiréis a la habitación, prepárate para la cama lo antes posible, teniendo en cuenta que, aunque la higiene femenina es de máxima importancia, tu marido no quiere esperar para ir al baño.]

19. Remember that you must have a splendid appearance when you go to bed . . . If it is necessary to apply facial creme or hair curlers, wait until he is asleep, since all that might be surprising to a man at that hour of the evening [Recuerda que debes tener un aspecto inmejorable a la hora de ir a la cama…; si debes aplicarte crema facial o rulos para el cabello, espera hasta que él esté dormido, ya que eso podría resultarle chocante a un hombre a última hora de la noche.

20. As far as marital relations, it is important to remember your obligations: [En cuanto respecta a la posibilidad de relaciones íntimas con tu marido, es importante recordar tus obligaciones matrimoniales:]

•If he needs to sleep, let him; do not pressure him or stimulate his intimate desires [Si él siente la necesidad de dormir, que sea así, no le presiones o estimules la intimidad.]

•If your husband suggests intimate relations, accede with humility, always keeping in mind that his satisfaction is more important than that of the wife [Si tu marido sugiere la unión, entonces accede humildemente, teniendo siempre en cuenta que su satisfacción es más importante que la de una mujer.]

•When the maximum point is reached during relations, a discrete moan on your part will be suficiente to indicate any enjoyment you may have felt [Cuando alcance el momento culminante, un pequeño gemido por tu parte es suficiente para indicar cualquier goce que hayas podido experimentar.]

•If your husband should ask for unusual sexual practices, be obedient and do not complain [Si tu marido te pidiera prácticas sexuales inusuales, sé obediente y no te quejes.]

•When your husband enters into a profound sleep, re-arrange the bed clothing, refresh yourself and apply your night creme and hair products. Then you can re-adjust the alarm clock in order to get up a little before your husband. This will allow you to have his cup of tea ready when he gets up. [Cuando tu marido caiga en un sueño profundo, acomódate la ropa, refréscate y aplícate crema facial para la noche y tus productos para el cabello. Puedes entonces ajustar el despertador para levantarte un poco antes que él por la mañana. Esto te permitirá tener lista una taza de té para cuando despierte.]

The important fact is not to analyze what is happening in every moment regarding putting these principles into practice (or at least not only), but rather to analyze what it means to have an ideal of a society that lasts for thirty years [Lo importante no es analizar qué ocurre con estos principios en la práctica (o no sólo) sino analizar qué significa que sean el ideal de una sociedad durante más de treinta años.]

It is common in Spain to link this official propaganda to clear manifestations of fascist ideology, but, in reality, this type of official advertising “advice” has much more to do with the perception of “women’s place” in the world than with ideological stances of states based on either leftist or rightist political ideologies.

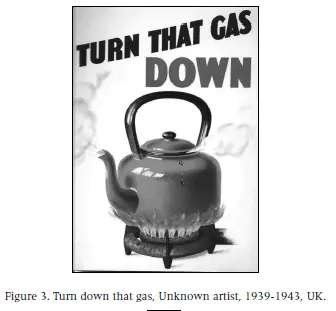

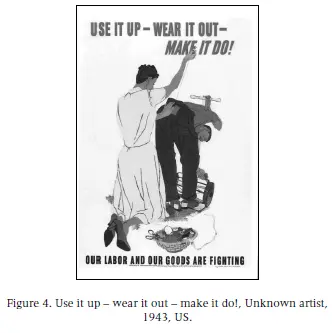

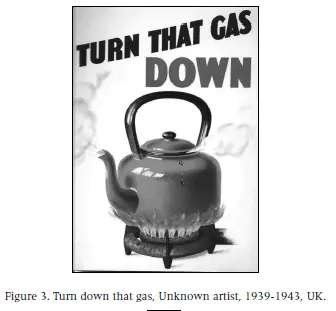

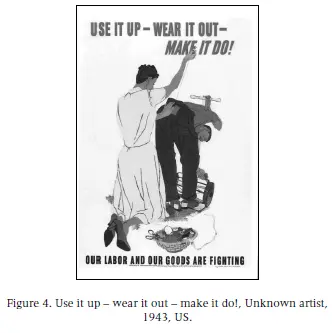

During WWI, the Depression (1929-early 1940s) and WWII, many state propaganda campaigns in Anglo countries focused on women’s roles in supporting “men’s efforts” – as if the global “efforts” were made only by men, while the local efforts were to be the work of women. In the UK, for instance, part of the wartime propaganda focused on the role of women as thrifty home-makers, as depicted in Figures 3 (Public Record Office, UK) and 4 (Office of War Information, US). It is significant that in Figure 4, with the subtitle “Our labour and our goods are fighting” show a woman and a man, each dedicated to a stereotypically sexist “job”; the woman is mending clothes while the man is bending down over a manual lawn-mower in order to fix it. Equally significant is the source for this poster, the Office of War Information .

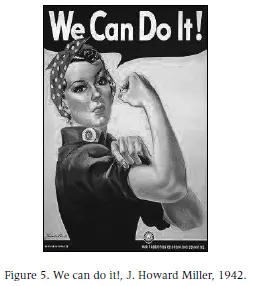

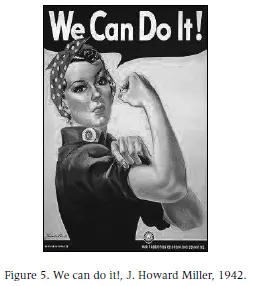

Posters such as these could have been part of an advertising campaign in any country during WWII. However, what is quite different from the Spanish state (Sección femenina) propaganda is that in the UK as well as in the US, there also appeared, both in WWI and WWII, posters and pictures in the press which showed women fulfilling traditionally male jobs, as in the well-known “Rosie the Riveter” portrayals (Figure 5, Westinghouse War Production Coordinating Committee, 1942).

In the UK, although women’s position was not as strong as the official propaganda may have made it out to be, UK women did work in industries during WWI, making a clear difference from the events occurring in Spain. UK women actually increased their inclusion in UK industries from the beginning to the end of WWI: some one million women became part of the UK work force (British National Archives). The same is essentially true for women in the US and also true for WWII.

However, it is what happened after the wars that should be noted. The British National Archives (WWI) document the following regarding what happened to women’s jobs, both after WWI and WWII:

The Representation of the People Act (February 1918) was widely portrayed as a ‘reward’ for the contribution of female labour to the war effort. However, while the Act granted the vote to all men over 21 (subject to sex month’s residency qualification), only women over the age of 30 were given the same privilege.

Further proof of the limits of the wartime march towards sexual equality was provided by the post-war blacklash against women’s employment –in particular, against the continued employment of married women. As soon as the conflict ended, the number of women working in munitions factories and transport fell away rapidly. Ex-service men reclaimed the jobs that had been performed by women during the previous four years. Moreover, even in long-standing bastions of female employment such as the laundry industry, women now found themselves in competition with disabled ex-servicemen.

As in France, the idea of women returning to the ‘rightful’ domestic place was a prominent theme in post-war Britain. Many of their undoubted advances between 1914 and 1918 were thus only partial or temporary.

In view of these UK/US documents, it appears that the Spanish state propaganda differed little from that of other states, in that women are, sooner or later, relegated to “their sphere”. However, the comparison does throw up the fact that women in the UK/US propaganda were called upon to go out of the home to occupy jobs previously held by men. This suggestion was nowhere to be found in the Spanish propaganda campaigns, perhaps because Spain was not attacked by foreign states. In some ways, the situation of the UK/US women seems more cruel, in the sense that women were used in industries by the State and then told to go back home. The consequent lack of earning power would, of course, ensure that women could not become economically independent of their husbands. In the Spanish propaganda, as in the UK/US propaganda, the role of women is clearly one of support for men’s roles. In the case of the UK/US propaganda and subsequent government legislation, women are used almost as pawns in the war effort: “now we need you; now we do not”.

Читать дальше