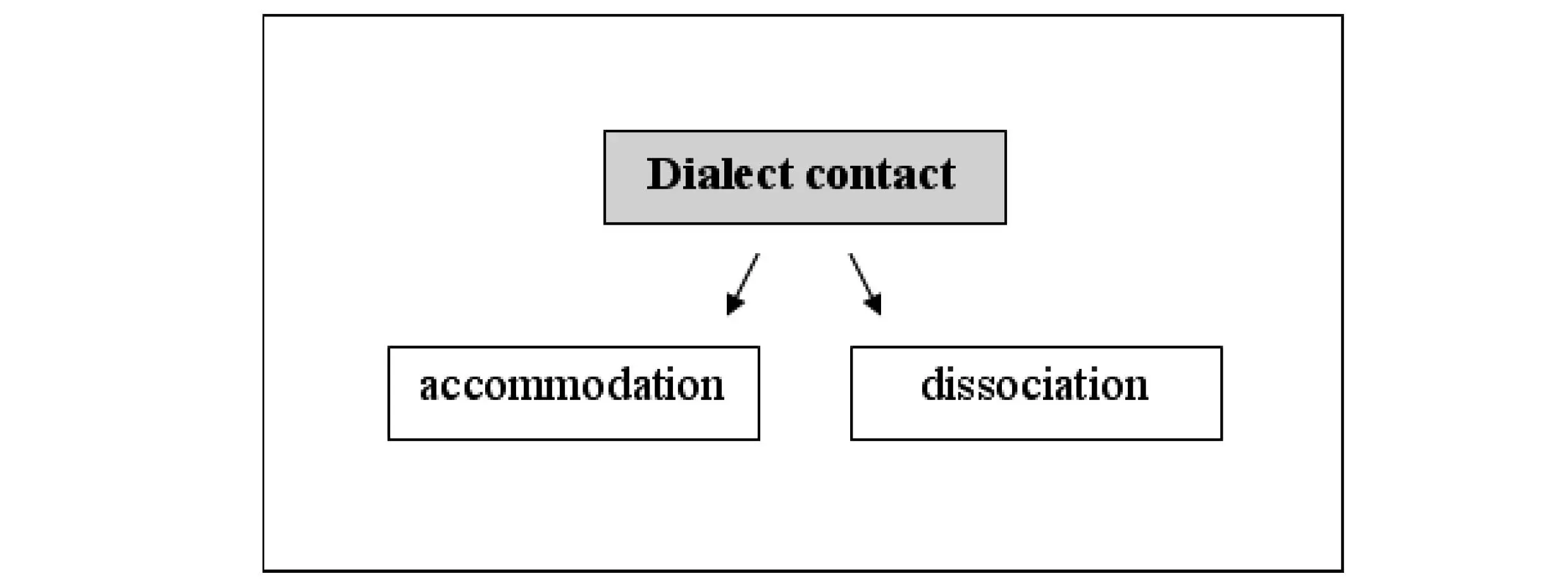

Figure 2.2:Accommodation process as described by Hickey (2000)

Both models can be justified. While Giles and Powesland (1975) focus on the social psychological side of accommodation, Hickey (2000) concentrates on the (long-term) linguistic outcome. However, an important point which has to be made is that while accommodation towards an interlocutor is foremost an unconscious process, dissociation or divergence in contact situations is very likely a conscious decision that a speaker makes. Yet this assumption needs to be tested. Researchers also have to trial whether accommodation has repercussions on long-term dialect contact outcomes.

Divergence patterns are widely recognised, i.e. young people in a speech community try to dissociate from older speakers, MC speakers dissociate from WC speakers and vice versa. For instance, Watt (2002) suggests that young speakers of Newcastle English do not want to be identified with the old “cloth cap and clogs” image of the city anymore and therefore turn to a more general Northern feature which he interprets as dialect levelling. In a similar vein, Hickey (2005) explains the recent changes in Dublin English. But not only is dissociation likely due to age but also due to social practice (cf. Moore 2010). Geographical dissociation is observable in the north-east of England, where Burbano-Elizondo (2006) and Llamas (2007) have shown that some groups do not want to be associated with Newcastle and therefore linguistically dissociate from its linguistic norms.

One possible macro-linguistic outcome of dialect contact is levelling . In recent years, this geolinguistic process is a ubiquitous finding in European languages (cf. Foulkes and Docherty 1999b; Britain 2002; Kerswill 2003 for Britain; Boughton 2005 for France; Hinskens 1996 for the Netherlands). Even though many researchers had already stated that dialect features are lost, Trudgill (1986: 98) proposes a model of levelling as a process in which contact between speakers with different dialectal backgrounds leads to the levelling of local dialects. He defines levelling as “the reduction or attrition of marked 1 variants” (emphasis in original).

Kerswill (2003: 224) unravels the terminological ambiguity of the term levelling in that he distinguishes between the two related concepts regional dialect levelling (= supralocalisation/diffusion) and levelling . He argues that the former concept is an outcome of geographical and social processes. The latter term should be used in the sense that Trudgill (see above) referred to it: the process of delimiting the linguistic variables of a variety.

Watt (2002) provides evidence that the local diphthongal variants of FACE and GOAT in Newcastle English are undergoing a levelling process and are replaced by the pan-northern monophthongal forms which young speakers associate with ‘modern northerners.’ They do so by adopting features which are perceived as non-local. Foulkes and Docherty (1999a: 14) point out that “it seems to be important, too, that the incoming features do not signal any other particularly well-defined variety, because of the potential signalling of disloyalty to local norms.”

Even though one can detect convergence of varieties in addition to the spread of innovative forms nationwide, these changes are locally determined and have to be analysed under this premise. “The specific attributes of any given locality are paramount in the explanation of the emergence of a supralocal variety” (Watts 2005: 19). On the surface geolinguistic processes might be accountable for variation within a variety but underlying patterns might indeed be the driving force for the variation. Thus, a detailed analysis of a change is necessary in order to detect and explain linguistic patterns.

2.1.3 Geographical diffusion

Another geolinguistic process that recently has attracted a lot of attention from scholars is geographical diffusion . In recent years, many studies in the dialect contact framework have been dealing with geographical diffusion of linguistic features. Boberg (2000: 1) describes geolinguistic diffusion as “the process by which linguistic changes spread geographically from one dialect or language to another” while Kerswill (2003: 223), defines it as “features [that] spread out from a populous and economically and culturally dominant centre” which entails a hierarchy. In particular consonants in British English are “torchbearers of geographical diffusion” (Kerswill 2003: 231), i.e. mainly consonants are diffusing across the country in a fast manner.

The diffusion of features is enhanced by loose social networks when a change progresses through a community. Mobility is the main reason for close-knit networks to break up into loose social networks. Close-knit networks are more traditional in their language choice than loose networks which often are the engines of diffusion. Individuals in loose networks are in contact with many people often on an infrequent basis, and often from outside a community which leads to various dialect contact situations. Therefore, they are usually the ones who adopt changes easier and faster than people in a closed circle of friends and family who are usually restricted in their contacts to small areas (cf. Milroy 1987: 202-203, 213).

Inter-speaker communication is thus the core issue for supralocal changes. Britain (2010b) emphasises the importance of physical and social space for the diffusion of linguistic features. The habits and daily routines of individuals have changed dramatically over the course of the 20 thcentury (cf. Watts 2005; Britain 2010b). Mobility, commuting, out of town shopping and attending university away from home are all social practices that have developed and increased only in the last sixty years or so (cf. Beal 2010). It is very likely that these factors are influencing the diffusion of linguistic features which is observed in Britain. Spatial practice (Britain 2010b) and mobility (Milroy 1987) are both interrelated factors which can have linguistic effects. Thus, spatial practice might be a social factor which influences dialectal variation.

Wolfram and Schilling-Estes (2006: 154) emphasise that dialect diffusion can happen on a horizontal dimension (geographically) as well as on a vertical dimension (socially). If a diffusional change arrives in a community, it is usually one social group that promotes the change before it extends to the use of other social groups. Thus, the use of linguistic features can be indexical for being part of a certain group. For example, the use of glottal stops used to be indexical for Cockney speakers, i.e. WC speakers living in London’s East End. This enregisterment has decreased in London recently due to the spread of this feature to other vertical dimensions. Thus, today T-glottaling is also used by middle class speakers in London (cf. Altendorf and Watt 2008). This linguistic feature has also spread horizontally so that the use of T-glottaling is found in other areas around Britain.

Chambers and Trudgill (1998: 167) identify four ways in which sound change can diffuse within a variety.

1. Sociolinguistic diffusion: social group to social group

2. Lexical diffusion: word to word

3. Linguistic diffusion: linguistic environment to linguistic environment

4. Spatial diffusion: place to place

These kinds of diffusion usually do not happen in isolation but are intertwined. In this particular study I will analyse the sociolinguistic, linguistic and spatial diffusion of selected features of Carlisle English.

Читать дальше