Historically, it was the literary canoncanon – or in Matthew ArnoldArnold, Matthew’s famous phrase, “the best that has been said and thought in the world” ( Culture and Anarchy 5) – that was to provide men and women with a sense of belonging to a higher order that was not, strictly speaking, transcendental, but that at least transcended the spatiotemporal limits of these individuals. Indeed, the term canon – which originally referred to the list of biblical books “accepted by the Christian Church as genuine and inspired” (OED) – itself bears witness to the quasi-religious function envisioned by Arnold for the monuments of high culture. In fact, ArnoldArnold, Matthew and other VictorianVictorian thinkers (e.g. Thomas Carlyle) had quite explicitly conceived of ‘high culture’ as a means both to cultivate the soul and to ensure social cohesioncohesion in the absenceabsence of religious certainties (Philip Davis 133–134; EagletonEagleton, Terry, Literary Theory 21). Agnes HellerHeller, Anges has captured well the utopian hopehope embodied in this high-cultural home that, ideally, would form the basis for universaluniversal belonging:

This home is not private, everyone can join it, and in this sense, it is also cosmopolitan. The assurance that everyone can join, refers both to the works that this home entails and to the visitors who enter with nostalgianostalgia and a quest for meaning. […] At the outset few works were admitted, now almost everything is. At the beginning there were also few visitors but later their number began to grow. Now, this, originally European […] home is visited by millions with all possible cultural backgrounds. (9)

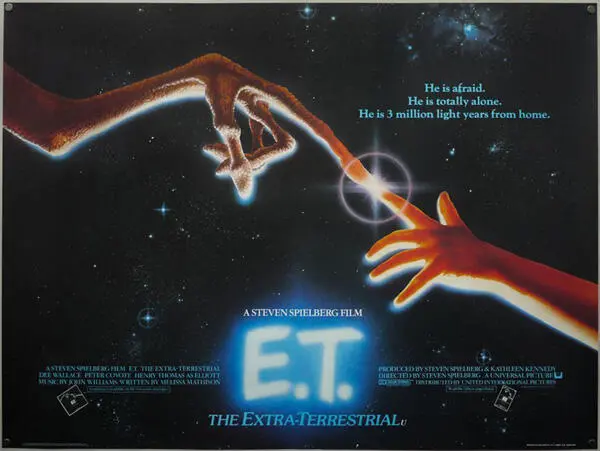

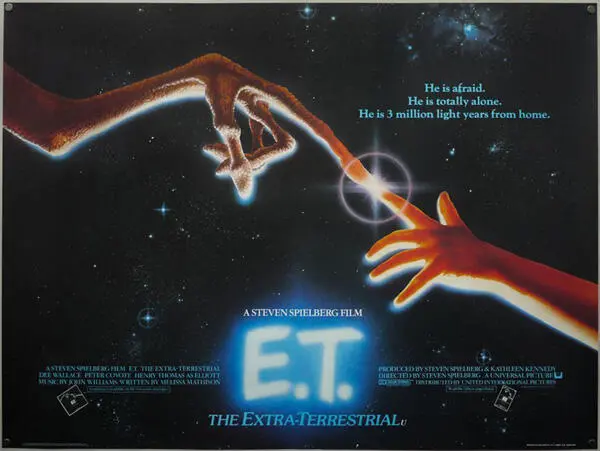

FIGURE 2:

FIGURE 2:

The iconography of the Sacred Heart of JesusJesus Christ is reflected in E.T.’s glowing heart. (Screenshot from E.T. ; © by Amblin/Universal Studios, used by permission)

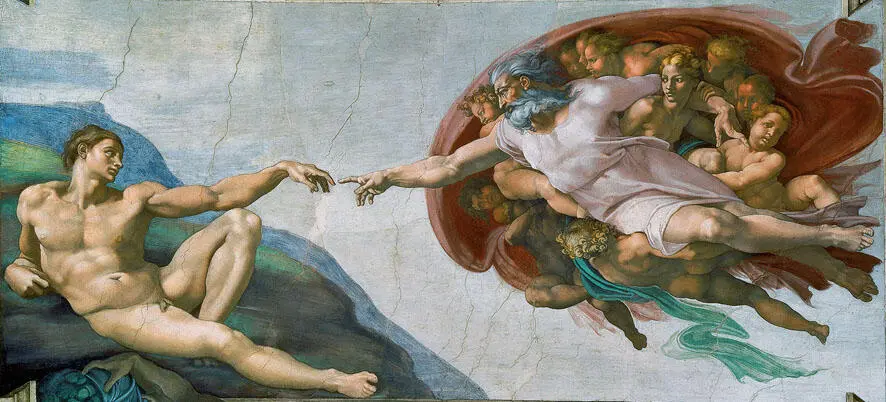

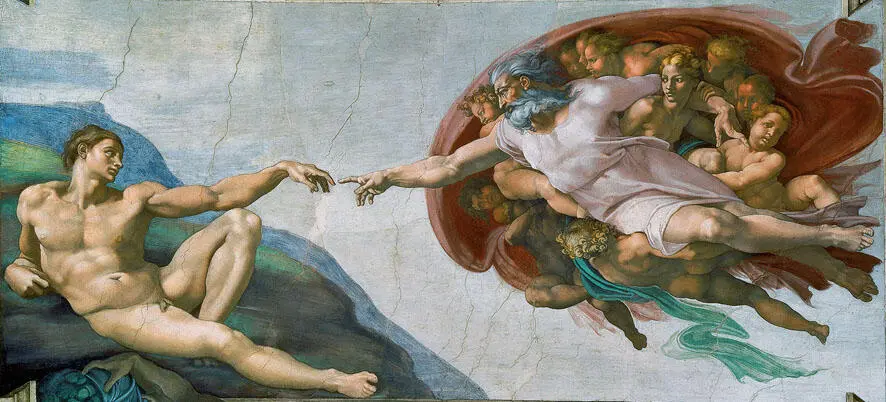

FIGURE 3:

FIGURE 3:

MichelangeloMichelangelo’s depiction of the creation is echoed in official ads for E. T .

HellerHeller, Anges herself notes, however, that the canoncanon, as envisioned by ArnoldArnold, Matthew and others, can only fulfill this function of creating a sense of universaluniversal belonging if it remains limited and exclusive; as soon as too many works are included, the canon’s ability to serve as a discursive home begins to crack and, ultimately, collapses (10). The Arnoldian ideal of the canon as home is thus in one sense inherently contradictory, for it can only serve as a discursive medium of universal inclusioninclusion if it simultaneously remains thoroughly exclusive in terms of the works it incorporates. Many will, in other words, not be directly represented in this assembly of high culture, and will therefore simply have to trust that those who are included will speak on their behalf. The logic of canonization thus resembles closely VictorianVictorian arguments for a limited franchise – a parallel that is arguably not accidental.

At any rate, those who happen to be unfamiliar with the canonical texts that, supposedly, form part of “a common cognitivecognition and cognitive background” (HellerHeller, Anges 10) may find that intertextualintertextuality references can also have a profoundly alienating effect. Comedies, for instance, are a highly allusive type of genregenre – and therefore they travel rather less well across cultural borders than other types of texts, for as Franco MorettiMoretti, Franco has observed, “laughter arises out of the unspoken assumptions that are buried very deep in a culture’s history: and if these are not your assumptions, the automatic component so essential to laughter disappears” (“Planet Hollywood” 99). When exposed to a comedycomedy from a very distant time or place, we may thus not experience the relief of shared laughter, but instead find ourselves puzzled and disoriented. More generally, allusionsallusion to unknown texts may confuse rather than reassure, provided the allusionallusion is nevertheless recognized as such. In E.T. , for instance, the film’s religious infrastructure arguably does not feel particularly alienating for anyone because it remains largely subliminalsubliminal; it is perfectly possible to watch the film without ever realizing that it draws on biblical imagery, so that even those who are unfamiliar with the story of JesusJesus Christ are unlikely to feel excluded from the film’s intended audience. However, E.T. also contains a reference to Peter Pan (to which we will return later), and because this reference is more explicit, it is possible that those who have never heard of this text will, at least momentarily, feel alienated by its intertextualintertextuality inclusioninclusion.

Let us briefly recapitulate the relation between religious transcendencetranscendence and the literary canoncanon as a secularsecular attempt to replace a lost metaphysicalmetaphysical home. VictorianVictorian intellectuals not only worried about statistics that indicated a sharp declinedecline in religious observance, but also themselves suffered from a sense of metaphysical ‘unbelonging’ prompted, among other things, by DarwinDarwin, Charles’s theory of evolutionevolution; at the same time, they hoped that the secular religionreligion of high culture, as encapsulated in the canon, might serve to alleviate the socially disruptive effects of unbelief or agnostagnosticismicism (a term that, tellingly, was coined by T.E. HuxleyHuxley, T.E. in 1869; see Philip DavisDavis, Philip 57). This is not to suggest that there was, at some moment in the nineteenth century (or, indeed, in the century that followed), a total collapse of religious beliefbelief amongst each and every segment of the population.16 Rather, the point is to emphasize that those who have no faith in a transcendental home also lack that sense of metaphysical belonging that religion has, for many, been able to provide. Bereft of a metaphysical home, these unbelievers may therefore seek other, more secular types of spiritual sheltershelter.

Following Georg LukácsLukács, Georg, we may describe the condition that results from a lossloss of faith as “transcendental homelessnesstranscendental homelessness” (40–41): a sense that human existence is purely contingentcontingent, and that humankind is adrift in a universe that is indifferent to human happinesshappiness or sufferingsuffering. Secular individuals can, in other words, no longer find comfort in the idea that life is securely anchored in transcendental meaning, but instead experience the Heideggerian anxietyanxiety & angst of finding themselves thrown into being or Daseinbeing or Dasein ( Being and Time 131): an existentialexistential & existential angst/trauma angst that HeideggerHeidegger, Martin explicitly describes as a sense of “not-being-at-home” (182; see Agnes HellerHeller, Anges 4; Mugerauer 43; O’Donoghue 139).17 Dominick LaCapraLaCapra, Dominick has suggested the term structural or existentialexistential & existential angst/trauma traumatrauma and shell shock to express the disturbing nature of this experience, though at the same time LaCapraLaCapra, Dominick is careful to distinguish this phenomenon from what he dubs historical traumatrauma and shell shock, which by contrast “is related to specific events, such as the Shoah or the dropping of the atom bomb on JapanJapanese cities” ( History and Memorymemory after Auschwitz 47). In the case of E.T. , we might therefore say that the film threatens to elide the distinction between the existentialexistential & existential angst/trauma threat of transcendental homelessnesshomelessness, and Elliott’s more limited, historical traumatrauma and shell shock of losing the comforting presence of his father. More generally, moreover, we may regard traumatrauma and shell shock as one of the most dramatic symptoms of not-being-at-home in the world, and the discussion of Herman MelvilleMelville, Herman’s Moby-Dick in chapter one will revolve precisely around such questions as transcendental homelessness and how it relates to existentialexistential & existential angst/trauma and historical forms of traumatrauma and shell shock.

Читать дальше

FIGURE 2:

FIGURE 2:

FIGURE 3:

FIGURE 3: