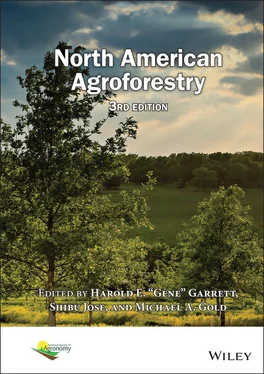

North American Agroforestry

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «North American Agroforestry» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:North American Agroforestry

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

North American Agroforestry: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «North American Agroforestry»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Explore the many benefits of alternative land-use systems with this incisive resource North American Agroforestry

North American Agroforestry

North American Agroforestry — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «North American Agroforestry», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Evolution of Management Systems

The United States inherited its forest management practices from Europe during the latter part of the 19th century and modified them to accommodate its large, sparsely populated country, which was rich in natural resources (Perlin, 1991; Williams, 1989). Prior to settlement by Europeans, Native Americans derived a variety of food, forage, and fiber products from forests while manipulating them primarily through the use of fire in what could be termed landscape‐scale agroforestry (Carroll, 1973; Cronon, 1983; Rossier & Lake, 2014; Russell, 1982). European pioneers also derived most of their energy and construction materials from the forest (Carroll, 1973).

The Industrial Revolution brought with it new harvesting and milling technologies, which greatly enhanced the efficiency with which the nation’s forest resources were exploited (Williams, 1989). Such forest practices accelerated as the population grew and became more urbanized. Around the turn of the 19th century, continuing over‐exploitation stimulated public concern and the birth of America’s conservation movement (Jordan, 1994), which included the development of professional forestry management agencies and academic institutions (Skok, 1996; Spencer, 1996). In 1905, the U.S. Forest Service was formally established to promote sustained‐yield forestry, designed to provide wood fiber from the nation’s forests forever (Steen, 1976). Conflicts over the single‐purpose use of public forest lands led the U.S. Forest Service to develop its multiple‐use approach to the management of national forests, which assured that, given a large enough and diverse enough land base, a full complement of forest uses could be enjoyed without conflict. Eventually, however, this approach also led to problems once the public began to question decisions being made about individual pieces of land, especially with respect to tradeoffs between wilderness preservation and timber production (Nash, 1982). Such concerns, together with a growing understanding of the impacts that plantation forestry has on biological diversity and the natural functioning of forest ecosystems, have stimulated the forestry profession to consider a new management strategy—ecosystem management—based on a holistic, integrative approach to land use (Coufal & Webster, 1996; Maser, 1994; Nunez‐Mir, Iannonne, Curtis, & Fei, 2015; Probst & Crow, 1991; Stankey, 1996). Parallel to those efforts and because of the growing interest in preserving our national forests free from production activities, national forests are increasingly off limits to harvest, shifting production forestry and harvesting to private lands (Adams, Haynes, & Daigneault, 2006). Simultaneously, there is a growing public cry for less governmental regulation and a return to a conservation ethic embodied in the idea of sound stewardship (Jordan, 1994). Likewise, it took a century and a half for American agriculture to develop to the level of complexity that required an integrated management approach (National Research Council, 1989). Native Americans were hunter‐gatherers, subsistence farmers, and also practiced indigenous forms of landscape‐scale agroforestry (Rossier & Lake, 2014), while early immigrants were primarily hunter‐gatherers and subsistence farmers (Russell, 1982). With population growth and industrial development came a growing need to improve food production capabilities and economic livelihoods of farmers to feed an ever‐increasing urban society. The mid‐1800s brought the development of the land grant university system and the initiation of an agricultural experiment station infrastructure that eventually built the world’s greatest system for the intensive cultivation of commercial food products (National Research Council, 1996; Russell, 1982).

Domestic and global marketing uncertainties, high costs for equipment, seed, chemical and energy inputs, high interest rates, and regional identity and security issues are forcing many modern farmers to develop integrated farming systems involving the production of a variety of products. More recent public concerns about the environmental impacts of modern farming practices and food safety are prompting the development of a new management approach based on agroecology principles: alternative or sustainable agriculture (LaCanne & Lundgren, 2018; Liebman & Schulte, 2015; National Research Council, 1989, 1991, 1996) More recently, eco‐agriculture and regenerative agriculture—integrating production and conservation at a landscape scale with the deliberate inclusion of perennial crops—have been put forth as new paradigms for linking production and conservation in our agricultural landscapes (Elevitch et al., 2018; Scherr & McNeely, 2007, 2008). Perennial trees and shrubs, and hence agroforestry practices, can serve important functions in such sustainable agricultural systems (Elevitch et al., 2018; Prinsley, 1992).

Evolution of North American Agroforestry

Although not defined as such until recently (Garrett et al., 1994; Gold & Hanover, 1987; Gordon & Newman, 1997; Rossier & Lake, 2014; Sinclair, 1999; Torquebiau, 2000), agroforestry‐like practices have been part of North America’s heritage. Native Americans and European pioneers practiced subsistence lifestyles based on integrated land use strategies that were similar in principle to the agroforestry being practiced by indigenous populations in today’s developing countries (Carroll, 1973; King, 1987; Rossier & Lake, 2014; Russell, 1982). The widespread use of these strategies, however, largely disappeared during the last century with the concurrent development of separate agricultural and forestry research and management infrastructures. Today, an integrated, subsistence lifestyle is the chosen standard of living for a few independent, free‐spirited individuals and an unfortunately necessary one for the economically marginalized rural poor. A few agroforestry practices survived into the mid‐20th century associated with long‐established organizations (e.g., the Northern Nut Growers Association) or as culturally acceptable complements to traditional farming enterprises (e.g., maple syrup production).

Periodic agricultural disasters have stimulated unique forestry activities that can also be considered agroforestry practices. In the 1930s, the Great Depression combined with the drought‐induced Dust Bowl in the Great Plains caused severe economic and environmental perturbations throughout the agricultural community and the nation. The formation of the Civilian Conservation Corps promoted many conservation activities including the planting of millions of trees as windbreaks and plantations to help protect eroding farmlands (Hudson, 1981). Such ecological problems also stimulated interest in the use and genetic improvement of nut trees to reclaim and promote production from lands marginal for conventional farming practices (Smith, 1950). The farm crisis of the 1980s was less dramatic on a large scale, but it had devastating economic and social impacts on many rural communities (Fitchen, 1991). In response, congressional actions established alternative agricultural programs such as the Conservation Reserve Program, Low Input Sustainable Agriculture (renamed the Sustainable Agriculture Program), and the Integrated Pest Management Program.

In the first decade of the 21st century, there was an increased interest in the production of biofuels and a concerted government effort to develop the technologies to make biofuels a reality. One unintended impact of the interest and support for biofuels, and particularly corn‐based ethanol, has been periodic increases in corn prices in the United States and around the world, igniting a “food versus fuel” debate. High commodity prices linked to the demand for biomass feedstocks for biofuels coupled with huge demand from China also resulted in farmers opting out of conservation programs and replacing conservation acres with commodity crops, with environmental consequences including increasing sediments and chemicals entering surface and ground waters (Jordan et al., 2007).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «North American Agroforestry»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «North American Agroforestry» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «North American Agroforestry» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.