I broached the idea to Hall, or perhaps he mentioned it first to me. Anyway, we both knew this was not a chance to be missed, though one thing we were certain of—that a story so perfect must be told with perfect accuracy. A whole literature has been burgeoning about it for a century, and if the ultimate account is to go into a novel, nothing of the truth must be sacrificed. For Romance is not capricious, it is an attitude of Fate, and Fate, my friends, is greatly to be respected. So on a visit to London in the Spring of 1931 I sought the assistance of Dr. Leslie Hotson, who knows the British Museum as if it were the lining of his trousers pocket. We hit on the perfect record worker, and in due time this lady and I laid hands on every scrap of pertinent evidence. We had photostatic copies of every page of the reports of the court-martial of the mutineers, hand written in beautiful copper plate. We assaulted the Admiralty, to which our bountiful thanks are due, for within its sacred precincts Commander E. C. Tufnell of His Majesty’s Navy made copies of the deck and rigging plans of the Bounty, and in his goodness even made an admirably detailed model of the ship. Meanwhile, booksellers, the mouldier the better, were put on the trail for volumes of the British Navy of the period. Engravers’ collections were searched for illustrations of Captain Bligh and of the rascals he set sail with. Item by item, a library unique in the annals of collecting was built, boxed, and shipped to Tahiti. The firm of Hall and Nordhoff hired by way of inspiration the first room that ever they lived in on the Islands. They pinned maps to the walls, stuck up deck and rigging plans, propped photographs of the model on the table in front of them, and, wonder of wonders, in spite of the fascination of their collection, in the face of the perfume blowing in at their windows, in defiance of the Heaven that Idleness is in the tropics, they fell to work!

Here is the book they have written. Read it, and you, too, will know that Romance has come into her own.

Ellery Sedgwick

Atlantic office, September 1st, 1932

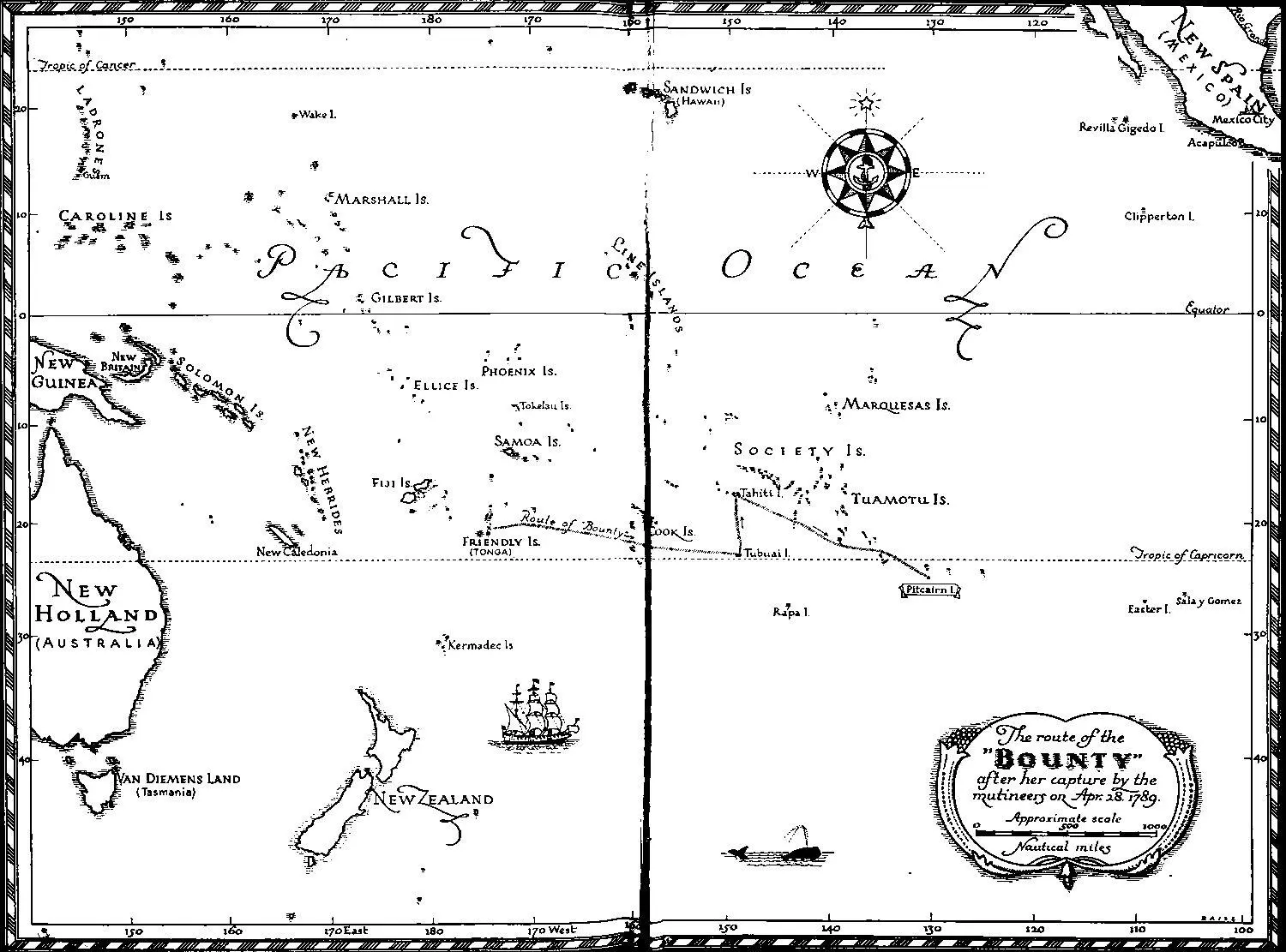

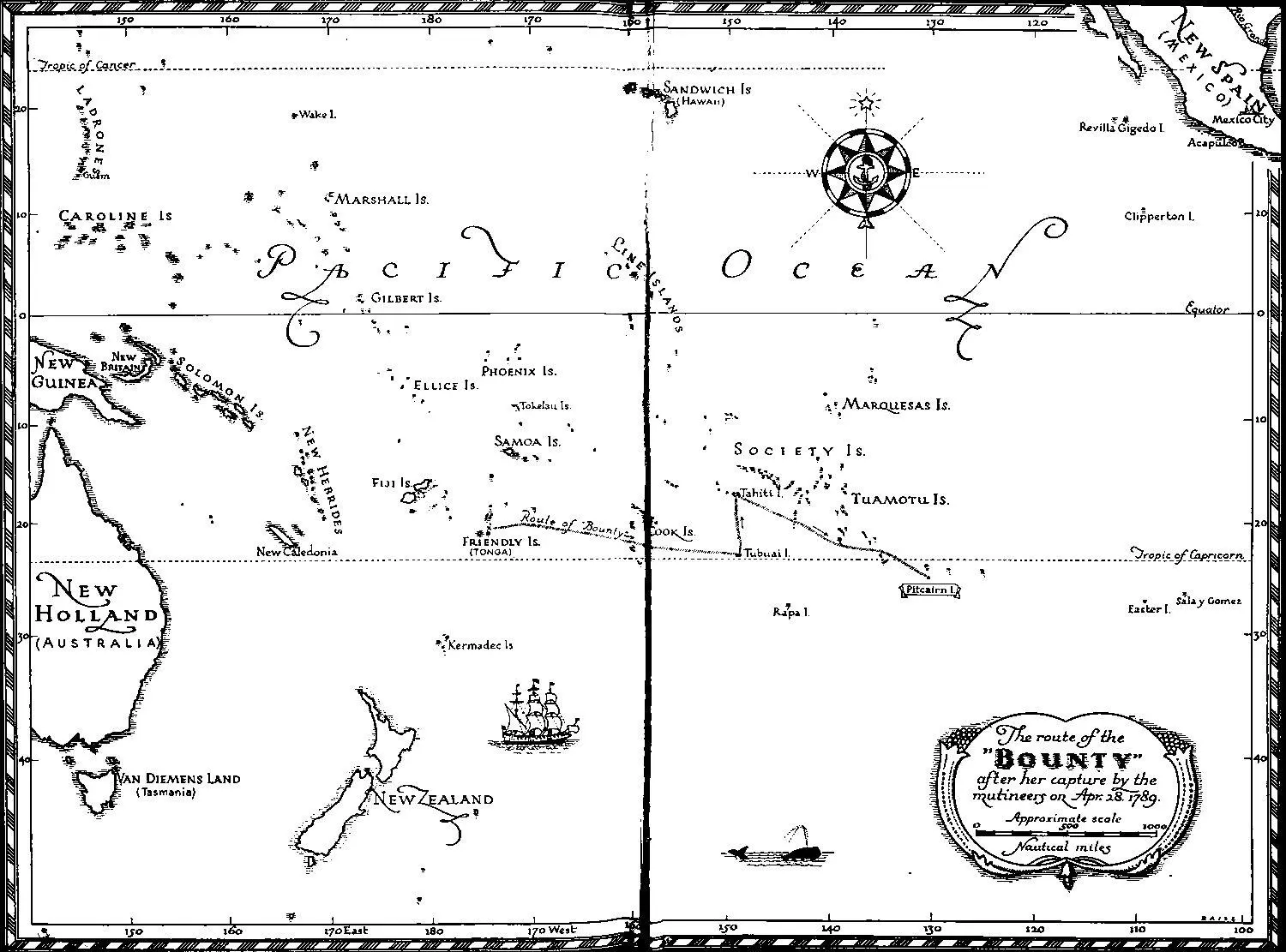

The Bounty Route

Table of Contents

The British are frequently criticized by other nations for their dislike of change, and indeed we love England for those aspects of nature and life which change the least. Here in the West Country, where I was born, men are slow of speech, tenacious of opinion, and averse—beyond their countrymen elsewhere—to innovation of any sort. The houses of my neighbours, the tenants’ cottages, the very fishing boats which ply on the Bristol Channel, all conform to the patterns of a simpler age. And an old man, forty of whose three-and-seventy years have been spent afloat, may be pardoned a not unnatural tenderness toward the scenes of his youth, and a satisfaction that these scenes remain so little altered by time.

No men are more conservative than those who design and build ships save those who sail them; and since storms are less frequent at sea than some landsmen suppose, the life of a sailor is principally made up of the daily performance of certain tasks, in certain manners and at certain times. Forty years of this life have made a slave of me, and I continue, almost against my will, to live by the clock. There is no reason why I should rise at seven each morning, yet seven finds me dressing, nevertheless; my copy of the Times would reach me even though I failed to order a horse saddled at ten for my ride down to Watchet to meet the post. But habit is too much for me, and habit finds a powerful ally in old Thacker, my housekeeper, whose duties, as I perceive with inward amusement, are lightened by the regularity she does everything to encourage. She will listen to no hint of retirement. In spite of her years, which must number nearly eighty by now, her step is still brisk and her black eyes snap with a remnant of the old malice. It would give me pleasure to speak with her of the days when my mother was still living, but when I try to draw her into talk she wastes no time in putting me in my place. Servant and master, with the churchyard only a step ahead! I am lonely now; when Thacker dies, I shall be lonely indeed.

Seven generations of Byams have lived and died in Withycombe; the name has been known in the region of the Quantock Hills for five hundred years and more. I am the last of them; it is strange to think that at my death what remains of our blood will flow in the veins of an Indian woman in the South Sea.

If it be true that a man’s useful life is over on the day when his thoughts begin to dwell in the past, then I have served little purpose in living since my retirement from His Majesty’s Navy fifteen years ago. The present has lost substance and reality, and I have discovered, with some regret, that contemplation of the future brings neither pleasure nor concern. But forty years at sea, including the turbulent period of the wars against the Danes, the Dutch, and the French, have left my memory so well stored that I ask no greater delight than to be free to wander in the past.

My study, high up in the north wing of Withycombe, with its tall windows giving on the Bristol Channel and the green distant coast of Wales, is the point of departure for these travels through the past. The journal I have kept, since I went to sea as a midshipman in 1787, lies at hand in the camphor-wood box beside my chair, and I have only to take up a sheaf of its pages to smell once more the reek of battle smoke, to feel the stinging sleet of a gale in the North Sea, or to enjoy the calm beauty of a tropical night under the constellations of the Southern Hemisphere.

In the evening, when the unimportant duties of an old man’s day are done, and I have supped alone in silence, I feel the pleasant anticipation of a visitor to Town, who on his first evening spends an agreeable half-hour in deciding which theatre he will attend. Shall I fight the old battles over again? Camperdown, Copenhagen, Trafalgar—these names thunder in memory like the booming of great guns. Yet more and more frequently I turn the pages of my journal still further back, to the frayed and blotted log of a midshipman—to an episode I have spent a good part of my life in attempting to forget. Insignificant in the annals of the Navy, and even more so from an historian’s point of view, this incident was nevertheless the strangest, the most picturesque, and the most tragic of my career.

It has long been my purpose to follow the example of other retired officers and employ the too abundant leisure of an old man in setting down, with the aid of my journal and in the fullest possible detail, a narrative of some one of the episodes of my life at sea. The decision was made last night; I shall write of my first ship, the Bounty, of the mutiny on board, of my long residence on the island of Tahiti in the South Sea, and of how I was conveyed home in irons, to be tried by court-martial and condemned to death. Two natures clashed on the stage of that drama of long ago, two men as strong and enigmatical as any I have known—Fletcher Christian and William Bligh.

When my father died of a pleurisy, early in the spring of 1787, my mother gave few outward signs of grief, though their life together, in an age when the domestic virtues were unfashionable, had been a singularly happy one. Sharing the interest in the natural sciences which had brought my father the honour of a Fellowship in the Royal Society, my mother was a countrywoman at heart, caring more for life at Withycombe than for the artificial distractions of town.

I was to have gone up to Oxford that fall, to Magdalen, my father’s college, and during that first summer of my mother’s widowhood I began to know her, not as a parent, but as a most charming companion, of whose company I never wearied. The women of her generation were schooled to reserve their tears for the sufferings of others, and to meet adversity with a smile. A warm heart and an inquiring mind made her conversation entertaining or philosophical as the occasion required; and, unlike the young ladies of the present time, she had been taught that silence can be agreeable when one has nothing to say.

Читать дальше