Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice: Problem Solved! 2nd Edition

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice: Problem Solved! 2nd Edition

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

For experienced veterinarians, pattern recognition combined with ‘fishing expeditions’ (i.e. ‘I have no idea what’s going on so I’ll just do bloods and hopefully something will come up!’) can result in a successful diagnostic or therapeutic outcome in many medical cases in first‐opinion practice. However, there are always cases that do not yield their secrets so readily using these approaches, and it is these cases that frustrate veterinarians, prolong animal suffering, impair communication, damage the trust relationship with clients and on the whole make veterinary practice less pleasant than it should be.

You also have to know about and remember lots of diagnoses for this approach to be effective. This is problematical if the veterinarian does not recognise or remember potential diagnoses (e.g. for Brutus) or if, as discussed previously, the pattern of clinical signs doesn’t suggest many feasible differentials (e.g. for Erroll). It is also less useful for inexperienced veterinarians or veterinarians returning to practice after a career break or changing their area of practice.

It is for all of these reasons that we hope this book will enhance your problem‐solving skills as well as build your knowledge base about key pathophysiological principles. We want to assist you to develop a framework for a structured approach to clinical problems that is easy to remember, robust and can be applied in principle to a wide range of clinical problems. The formal term for this is problem‐based inductive clinical reasoning .

Problem‐based inductive clinical reasoning

In problem‐based inductive clinical reasoning, each significant clinicopathological problem is assessed in a structured way before being related to the other problems that the patient may present with. Using this approach, the pathophysiological basis and key questions (see the following sections) for the most specific clinical signs the patient is exhibiting are considered before a pattern is sought. This ensures that one’s mind remains more open to other diagnostic possibilities than what might appear to be initially the most obvious and thus helps prevent pattern‐based tunnel vision.

If there are multiple clinical signs – for example, vomiting, polydipsia and a pulse deficit – each problem is considered separately and then in relation to the other problems to determine if there is a disorder (or disorders) that could explain all of the clinical signs present. In this way, the clinician should be able to easily assess the potential differentials for each problem and then relate them rather than trying to remember every disease process that could cause that pattern of particular signs. It is important that the signalment of the patient is seen as a risk factor, but this should not blind the clinician to potential diagnoses beyond what is common for that age, breed and sex.

Thus, we do look for patterns but not until we have put in place an intellectual framework that helps prevent tunnel vision too early in the diagnostic process .

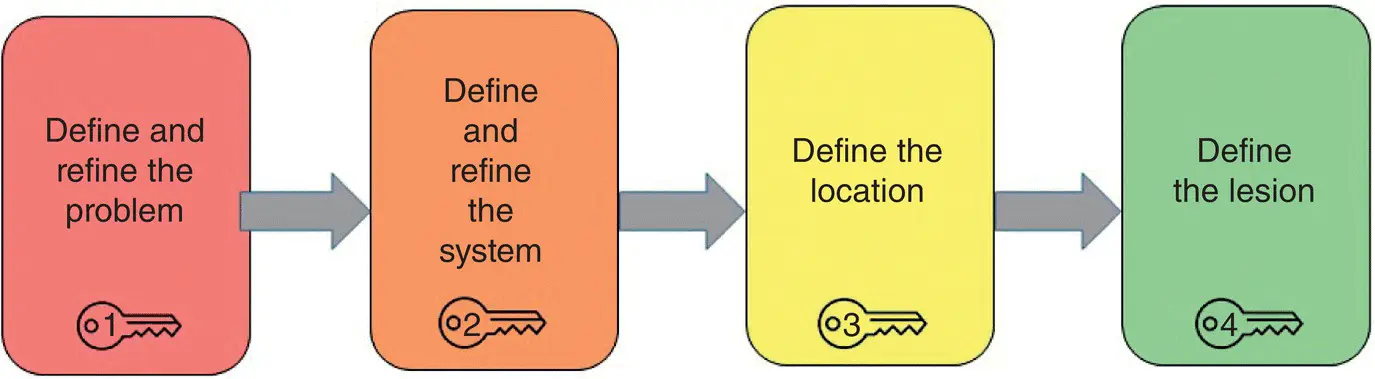

Figure 2.2shows the steps in the clinical reasoning flow. As each step is explained you will see the numbered keys to help you understand where you are in the diagnostic process. We use these steps, their colours and numbered keys throughout the book to help ‘anchor’ the process for you through the repetition shown in Figure 2.1. Colour bars or shading are also used to identify introductory concepts (blue), diagnostic approach and steps (brown) and key introductory and summary points (purple).

Figure 2.2 Clinical reasoning step‐by‐step.

Essential components of problem‐based clinical reasoning

The problem list

The initial step in logical clinical problem‐solving is to clarify and articulate the clinical problems the patient has presented with. This is best achieved by constructing a problem list – either in your head or, in more complex cases, on paper or the computer.

For example, for Erroll the problem list in the order the problems are reported would be:

1 Vomiting

2 Anorexia

3 Depression

4 Dysuria and haematuria.

Why is constructing a problem list helpful?

It helps make the clinical signs explicit to our current level of understanding.

It transforms the vague to the more specific.

It helps the clinician determine which are the key clinical problems (‘hard findings’) and which are the ‘background noise’ (‘soft findings’) that may inform the assessment of the key problems but do not require specific assessment.

And most importantly, it helps prevent overlooking less obvious but nevertheless crucial clinical signs.

Prioritising the problems

Having identified the presenting problems, you then need to assign them some sort of priority on the basis of their specific nature.

For example, anorexia, depression and lethargy are all fairly non‐specific clinical problems that do not suggest involvement of any particular body system and can be clinical signs associated with a vast number of disease processes.

However, clinical signs such as vomiting, polydipsia/polyuria, seizures, jaundice, diarrhoea, pale mucous membranes, weakness, bleeding, coughing and dyspnoea are more specific clinical signs that give the clinician a ‘diagnostic hook’ he/she can use as a basis for the case assessment.

As the clinician increases understanding of the clinical status of the patient, the overall aim is to seek information that allows them to define each problem more specifically (i.e. narrow down the diagnostic options) until a specific diagnosis is reached.

For example, for Erroll the prioritised problem list would be:

1 Vomiting

2 Dysuria and haematuria

3 Anorexia

4 Depression.

This is because vomiting and dysuria/haematuria are specific problems, and their assessment will hopefully assist in reaching a diagnosis – they are our ‘diagnostic hooks’. Anorexia and depression will be explained by the underlying disorder and are important to note but are not ‘diagnostic hooks’ for this case – they are the ‘background information’.

Specificity is relative!

The relative specificity of a problem will, however, vary depending on the context.

For example, for a dog that presents with intermittent vomiting and lethargy, vomiting is the most specific problem, as in all likelihood the cause or consequences of the vomiting will also explain the lethargy.

In contrast, for the dog that presents with intermittent vomiting and lethargy and is found to be jaundiced on physical examination, jaundice is the most specific clinical problem. This is because:The majority of causes of jaundice can also cause vomiting, but the reverse is not true, that is, there are many causes of vomiting that do not cause jaundice.Thus, there is little value in assessing the vomiting as the ‘diagnostic hook’, as it will mean that many unlikely diagnoses are considered, and time and diagnostic resources may be wasted.

In this case, assessment of jaundice will lead more quickly to a diagnosis than that of vomiting, as the diagnostic options for jaundice are more limited than those for vomiting.

In other words, although you identify and consider each problem to a certain degree, you try to focus your diagnostic or therapeutic plans on the most specific problem/s (the ‘diagnostic hook/s’) if ( and this is important ) you are comfortable that the other clinical signs are most likely related. If you are not convinced that they are all related to a single diagnosis, then you need to keep your problems separate and assess them thoroughly as separate entities, keeping in mind they may or may not be related.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.