Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice: Problem Solved! 2nd Edition

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice: Problem Solved! 2nd Edition

Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As mentioned, because the epiglottis does not close, regurgitating patients are at considerable risk of aspirating gastric contents. Thus, if an owner reports that his/her animal developed a cough at the same time it started ‘vomiting’, the clinician should be alert to the possibility that aspiration has occurred and that this is more likely to occur with regurgitation than vomiting.

There is a caveat, however, which should be kept in mind. Patients who have experienced serious vomiting of acidic gastric contents may develop a secondary oesophagitis and present with signs suggestive of both vomiting and regurgitation or reflux. Usually, vomiting will have been the first sign noted. Animals that ingest caustic or irritant material causing oesophagitis and gastritis may also present with signs of both vomiting and regurgitation.

Haematemesis

Patients may vomit fresh blood or digested blood. Digested blood has the appearance of coffee grounds and is often not recognised by the owner as blood (understandably). Owners are usually extremely concerned if fresh blood is observed in vomitus, though this may not be of great clinical consequence if it has resulted simply from the physical effect of intense vomiting rupturing a small superficial blood vessel.

Nausea

While most patients who vomit will also be nauseous, it is important to recognise, as mentioned earlier, that the neural pathways involved in nausea and vomiting are not the same. Indeed, the neural pathways involved in nausea are still not well understood.

Define and refine the system

Define and refine the system

Primary vs. secondary gastrointestinal disorders

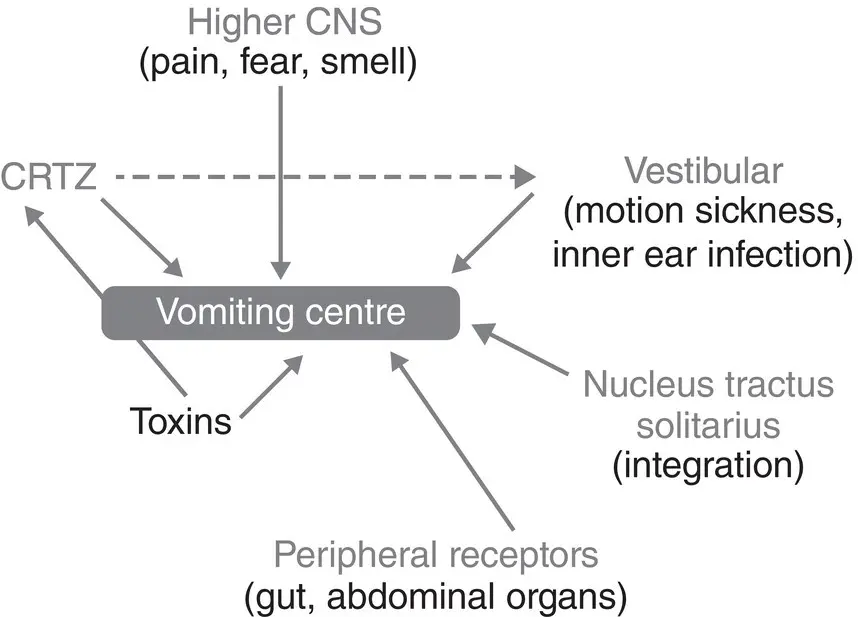

Reviewing the physiology of vomiting as discussed in the previous section and as shown in Figure 3.1, it is apparent that vomiting may occur due to primary GI disease or from secondary or non‐GI disease.

In contrast, regurgitation is almost always due to primary oesophageal disease ( Table 3.1).

Figure 3.1 The relationship between the elements of the emetic reflex.

Primary GI diseases are those where there is specific primary GI pathology such as gut disturbance due to dietary indiscretion, inflammation, infection, parasites, obstruction or neoplasia. There may be metabolic consequences of the GI disease, but the primary pathology is in the GI tract .

Secondary GI disease is where the vomiting or regurgitation has occurred due to pathology elsewhere in the body – the gut is just the ‘messenger’. Abnormalities of other body systems may indirectly cause vomiting either due to the action of toxins on the CRTZ, vomiting centre and vestibular system or by stimulation of peripheral non‐GI‐associated vomiting receptors.

Examples would include renal failure, liver disease, ketoacidososis, pancreatitis, hypercalcaemia, hypoadrenocorticism and other metabolic disorders. In most cases, there is no pathology identifiable in the gut, or where there is, for example, ulceration secondary to liver disease, uraemia or hypoadrenocorticism, the primary cause is the metabolic disorder. While symptomatic management strategies might be directed at the gut pathology in these cases (such as the use of anti‐ulcer drugs), there is no diagnostic benefit to imaging the gut, for example, by endoscopy.

Why is it important to differentiate primary from secondary GI disease?

It is important to determine whether primary or secondary GI disease is occurring in the vomiting or regurgitating animal, as much time and money can be wasted if the wrong system is investigated. As discussed in Chapter 2, the range of diagnoses to consider, diagnostic tools used and potential treatment or management options for primary, structural problems of a body system such as the GI tract are often very different compared to those relevant to secondary, functional problems of that system. Investigation of primary GI disease often involves some form of imaging modality (radiology, ultrasound, endoscopy and surgery) and/or biopsy. Routine haematology and biochemistry are often of little diagnostic value in GI disease, although they may give clues about the clinical status of the patient. In contrast, for secondary GI disorders, haematology, biochemistry and other tests are often critically important in progressing towards a diagnosis.

It is also important to appreciate that there are cases of primary GI disease causing vomiting, such as gastroenteritis caused by dietary indiscretion or other irritants, that can be safely treated symptomatically, as the cause is transient and will resolve within days without specific treatment. Symptomatic management such as withholding food, antiemetic treatment and/or dietary change is appropriate for these patients. However, there are few, if any, secondary GI causes of vomiting (such as liver disease, renal failure, hypoadrenocorticism and hypercalcaemia) where the cause is transient, which will respond to symptomatic treatment and/or will resolve without specific therapeutic intervention.

The uncommon secondary GI causes of regurgitation all cause megaesophagus ( Table 3.2), so the clinical decision pathway leading to their diagnosis begins with the diagnosis of megaoesphagus by endoscopy or diagnostic imaging and then the search for a metabolic cause. As mentioned, symptomatic treatment of regurgitation without establishing the cause is not prudent.

Thus, the clinician’s clinical reasoning, in the consultation room , about whether primary or secondary GI disease is likely to be present is a crucial component of the rational management of patients reported to be vomiting or regurgitating and of clear communication with the client.

What are the clues that the patient has primary or secondary GI disease causing vomiting?

Primary GI disease should be strongly suspected if:

An abnormality is palpable in the gut, for example, foreign body and intussusception

The vomiting is associated with significant and concurrent diarrhoea

The patient is clinically and historically normal in all other respects

The onset of vomiting significantly preceded any development of signs of malaise – depression and/or anorexia

The vomiting is consistently related in time to eating (although this can also occur with pancreatitis).

It is important to note, however, that primary GI disease cannot be ruled out even if none of the aforementioned features are present. For example, vomiting may be delayed for some hours (up to 24 hours) in animals with non‐inflammatory gastric disorders. Animals with foreign bodies or secretory disorders of the bowel often vomit despite not eating. In lower bowel disorders, vomiting more commonly occurs at variable times after eating.

Animals with primary GI may also be depressed and inappetant due to the lesion (there are neural inputs to the satiety centre in the hypothalamus from the gut) or due to the secondary effects of prolonged vomiting with dehydration or electrolyte disturbances. Usually, the malaise will occur at the same time or after the onset of vomiting.

Thus, the features in the aforementioned bulleted list are strong clues that primary GI disease is present, but their absence does not preclude it.

Animals with secondary GI disease are vomiting due to the effect of toxins on the vomiting centre or CRTZ or because of the stimulation of non‐GI‐associated peripheral receptors. The vomiting is usually unrelated to eating – except pancreatitis in dogs .

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Practice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.