RewildingA practice of conservation where ecological functions and evolutionary processes, which are thought to have existed in past ecosystems or before human influence, are deliberately restored or created; rewilding often requires the reintroduction or restoration of large predators to ecosystems

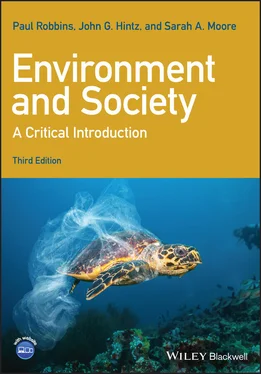

There is plenty of precedent for such activities. In the sand hills of Nebraska, for example, along the Platte River, hundreds of thousands of migrating Sandhill Cranes (Grus Canadensis) congregate every spring, on the migration south to the Gulf Coast, using the sandbars of the river as nightly perches and protection from predators (Figure 1.1). This stretch of the river is a critical habitat for a booming population of the elegant, strong, and giant birds, and a destination for visitors from around the world every year.

Figure 1.1 Sandhill cranes of the Platte River. A half million of these birds congregate annually. Source : Diana Robinson Photography/Moment/Getty Images.

But this is by no means a “natural” condition. Owing to the century-old human damming of the river, the Platte lost its powerful ability to flood, and so its sandbars gave way to shrubby vegetation, overgrowth and habitat loss for cranes and other species. Only by scouring the river bed every year, with gigantic machinery, do people manage to maintain this habitat and allow the critical sandbars of the river to return. The returning birds also glean from nearby famers fields as they rest on their long journey; people are providing a crucial subsidy to their non-human visitors. The Sandhill Crane was on the brink of extinction in the middle of the twentieth century. It has come roaring back in recent years, owing to human’s ability to understand their influence on the environment, and their willingness to consider their responsibility to the land.

More radically, in Flevoland, a province in the Netherlands, wild species are thriving as never before. As in the late Pleistocene (10 000 years ago), Red Deer roam the landscape, feral horses travel in herds, and an ecosystem of foxes and wild birds has arisen, including egrets and wild geese. Aurochs – the massive wild cattle of Europe – have been extinct for centuries, but their human-bred cousins, Heck Cattle, graze the landscape, their long horns and hairy forms rumbling across the marshland (Figure 1.2). This 15 000-acre wilderness, called Oostvaardersplassen, is wholly artificial, and filled with wild life. Remarkably, all this wildlife is thriving in one of the places on Earth most densely populated by people. For safari visitors, who pay US$45 for a visit to the park, there is no question that the place creates a great sense of wonder, as visits to wild places do for most all of us in a world that is increasingly encroached by human activity, pollution, and influence.

Figure 1.2 Heck Cattle, introduced to replace the extinct Aurochs. Source : Simon Vasut/Shutterstock.

These views from Canada, Nebraska, and the Netherlands makes our global situation easier to understand, though perhaps no simpler to solve. The contradictory proposition – dramatically transforming the environment in ways that may preserve the environment – is a metaphor for the condition of our longstanding relationship to the non-human world. Nor is this problem rare. Yellowstone National Park in the United States, though heralded as a wilderness, was created through the violent extirpation of the dozens of native tribes who lived in the region, transformed its landscapes, and relied on the resources of what would become a park devoid of people. Coffee plantations throughout Asia and Latin America, though regarded purely as economic and artificial landscapes, often teem with wild birds, mammals, and insects, all beyond the intent and control of farmers, conservationists, or anyone else for that matter. Everywhere we seek some place beyond people, the marks of human creation and destruction confront us, and wherever the works of humans are in evidence, there are non-human systems and creatures, all operating in their own way.

Decisions made in places like Isle Royale, therefore, cannot be made solely on the basis that the region is a “natural” one, nor a “social” one. The area is simultaneously neither and both, with animals, plants, and waterways springing from human interventions, creating altogether new habitats and environments. Wildlife parks and coffee plantations are both landscapes of the Anthropocene, therefore, one term for our current era, when people exert enormous influence on the Earth, but where control of these environments and their enormously complex ecologies is inevitably elusive.

AnthropoceneA metaphoric term sometimes applied to our current era, when people exert enormous influence on environments all around the Earth, but where control of these environments and their enormously complex ecologies is inevitably elusive

Such a condition, however, raises more questions than it answers. If a “natural” condition is unavailable to adjudicate what a wild place should look like and what its use or purpose might be, then wild nature will inevitably be, in part, a product of human choices. Who should control such decisions? Lands long-ago taken from Indigenous communities, as in the case of the Platte River, might arguably be best managed or comanaged by Native communities. What criteria will be used for deciding the ecological arrangements that follow? Should it be for the utility of people or the benefit of non-human nature? And what systems should be put in place to enact decision-making? Should nature be governed by free markets or rather by local collective institutions, or something else entirely? In short, environmental decisions in the Anthropocene are inherently and inevitably social, political, economic, ethical, and cultural.

If decisions about what to do (and what not to do) are to be made, therefore, and the larger complex puzzle of living within nature is to be solved, we need tools with which to view the world as simultaneously social and natural. For example, viewed as a problem of ethics, the restoration of a wilderness in Lake Superior becomes one of sorting through competing claims and arguments about what is ethically best, weighing on whose behalf one might make such argument, that of people or that of the animals themselves. From the point of view of political economy, by contrast, one would be urged to examine what value is created and destroyed in the transformation of these muddy lands, whose specific species are selected and why, whose pockets are filled with money in the process, and how decisions are controlled and directed through circuits of expert power and conservation authority. Indeed, there is no shortage of ways to view this problem, with population-centered considerations competing with those that stress market logics, and arguments about public risk perception competing with those about equal access to the park. What “lenses” can and should we use to look at environmental issues?

This book is designed to explain these varied interpretive tools and perspectives and show them in operation. Our strategy is first to present the dominant modes of thinking about environment–society relations and then to apply them to a few familiar objects of the world around us. By environment, we mean the whole of the aquatic, terrestrial, and atmospheric non-human world, including specific objects in their varying forms, like trees, carbon dioxide, or water, as well as the organic and inorganic systems and processes that link and transform them, like photosynthesis, predator–prey relationships, or soil erosion. Society, conversely, includes the humans of the Earth and the larger systems of culture, politics, and economic exchange that govern their interrelationships.

Читать дальше