MonopsonyA market condition where there is one buyer for many sellers, leading to perverted and artificially deflated pricing of goods or services

Other asymmetries also plague markets. One of the most serious is that of monopoly, where many buyers face one service provider or owner, or monopsony, where many sellers face a single buyer. In either case, the individual or firm is in a position to set prices and buy and sell goods or services free from competition and with no incentive to be efficient. Neither are such cases rare; the histories of the American and European capitalist economies are filled with cases where monopolies and monopsonies emerged through the concentration of wealth (in railroads, meat packing, and communication, among many). For environmental goods and services, the record has been equally spotty. Most municipal water provision in the United States, for example, was developed by private companies in the 1800s. The failure of these utility monopolies to efficiently manage and price water, however, led to the transition of most such utilities to state control.

A further problem is raised if we consider that many of the potential parties in a contractual arrangement or in a market have not yet been born. People may negotiate with one another over the relative value of cutting down a forest or enjoying its timber for construction, but what about people a hundred years from now? Do they have a place in such a market? A strict adherent to market logics would make no provision for such people. Getting environmental economics right is difficult enough without considering future generations, after all! Alternatively, it could be argued that both economic development and conservation in the present, in whatever market-negotiated combination, are always in the interest of future generations, who benefit from better economic and environmental conditions.

Market-Based Solutions to Environmental Problems

We have seen that markets can fail and even vociferous supporters of market environmentalism admit the necessity of some form of regulatory guidance of the economy. Nevertheless, a range of market-based policy solutions have been introduced in recent years to solve countless environmental problems. These each, in some way, for better or for worse, use the concepts of incentives, ownership, pricing, and trading to address environmental problems ( Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Market-based solutions. An overview of some dominant environmental regulatory mechanisms that involve market components and are based in part on market logics. Note that in all cases the state remains an important player in making markets work and achieving environmental goals

| Regulatory mechanism |

Concept |

Market component |

Role of the state |

| Green taxes |

Individuals or firms participate in “greener” behavior by avoiding more costly “brown” alternatives |

Incentivized behavior |

Sets and collects taxes |

| Cap and trade |

Total amount of pollutant or other “bad” is limited and tradable rights to pollute are distributed to polluters |

Rewarding efficiency |

Sets limits and enforces contracts |

| Green consumption |

Individual consumers choose goods or services based on their certified environmental impacts, typically paying more for more benign commodities |

Willingness to pay |

Oversees and authenticates claims of producers and sellers |

One of the most direct ways to harness the market, and therefore to influence environmental decision-making by people and firms, is through artificially altering prices. According to the market response model, after all, it is increasing prices that drive providers to search for new sources, innovators to substitute, consumers to conserve, and alternatives to emerge. Taxing certain goods or services, and so increasing prices, should result in either decreased use of these resources or creative innovation of new sources or options. The money raised through the tax can be used directly by the government either to provision services or to search for alternatives.

Many examples of such “green taxes” exist. Facing landfill costs, labor expenses, and related costs in the provision of garbage disposal, for example, some municipalities have required households to dispose of all waste in special trash bags, purchased by consumers themselves, and often costing a dollar or more each. The results have been greatly increased recycling and more careful attention by consumers to packaging and waste. By internalizing the costs of trash to consumers, there has been an observed decrease in the flow of garbage from households.

More radically, such taxes have been proposed for the control of greenhouse gases that drive global warming. Sweden enacted a carbon tax in 1991, followed by other countries, including the Netherlands, Finland, and Norway. This tax is leveled against oil, natural gas, coal, and a range of fuels. Such taxes have also been considered in the United States and the European Union, although they face significant political opposition.

Trading and Banking Environmental “Bads”

Also prominent among these market approaches are policy efforts that draw upon Coase’s insights to reduce environmental problems as efficiently as possible, using contractual exchange. Such mechanisms usually take the form of “ cap and trade.” Here, the state determines a regulatory maximum for emissions of an environmental hazard and allows firms to meet the goal themselves or to pay other firms, who are able to reduce outputs more efficiently, to do so for them. This achieves the same results as traditional regulation, but does so at lower overall cost (and so economists describe this outcome as “more efficient”).

Cap and TradeA market-based system to manage environmental pollutants where a total limit is placed on all emissions in a jurisdiction (state, country, worldwide, etc.), and individual people or firms possess transferable shares of that total, theoretically leading to the most efficient overall system to maintain and reduce pollution levels overall

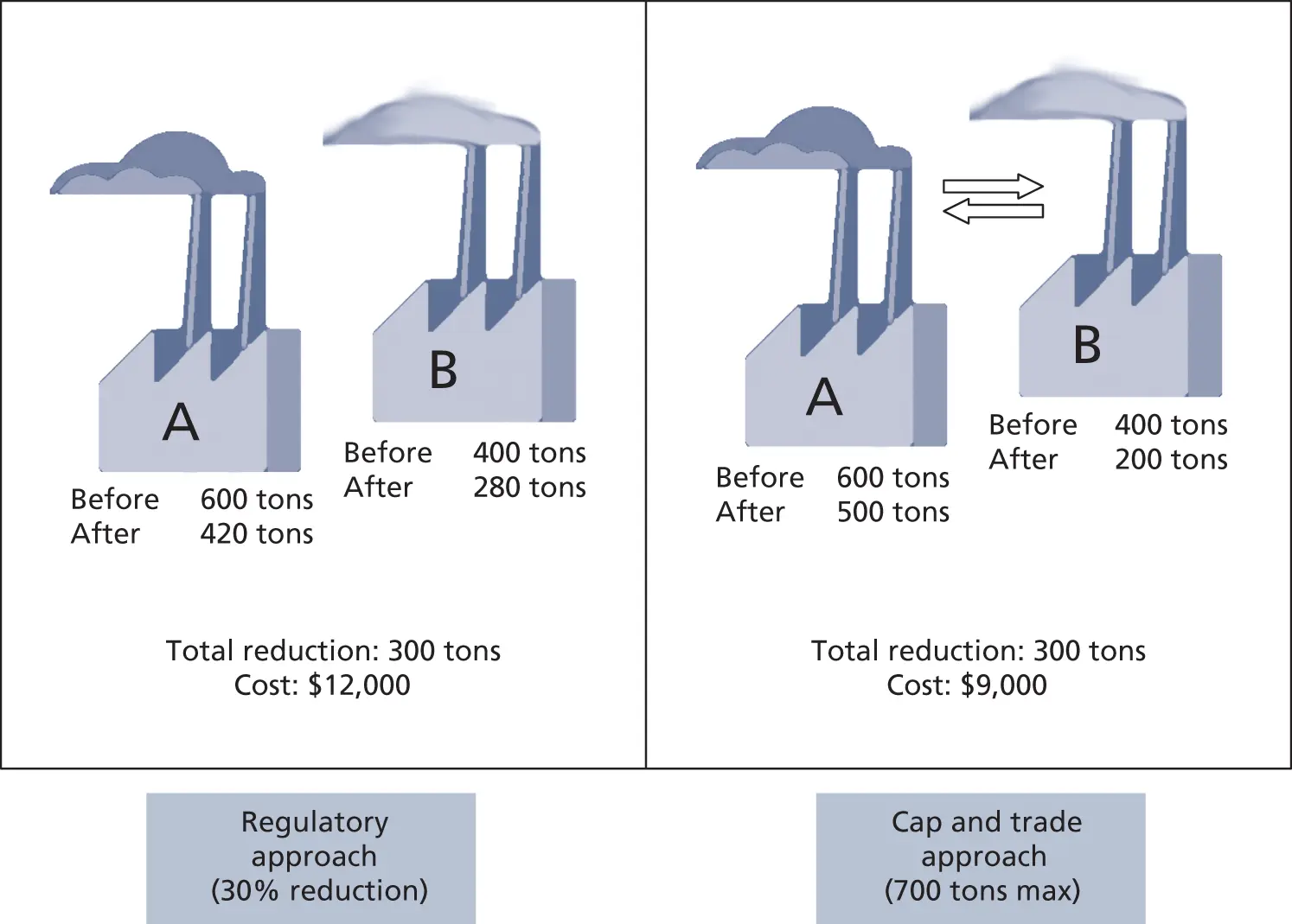

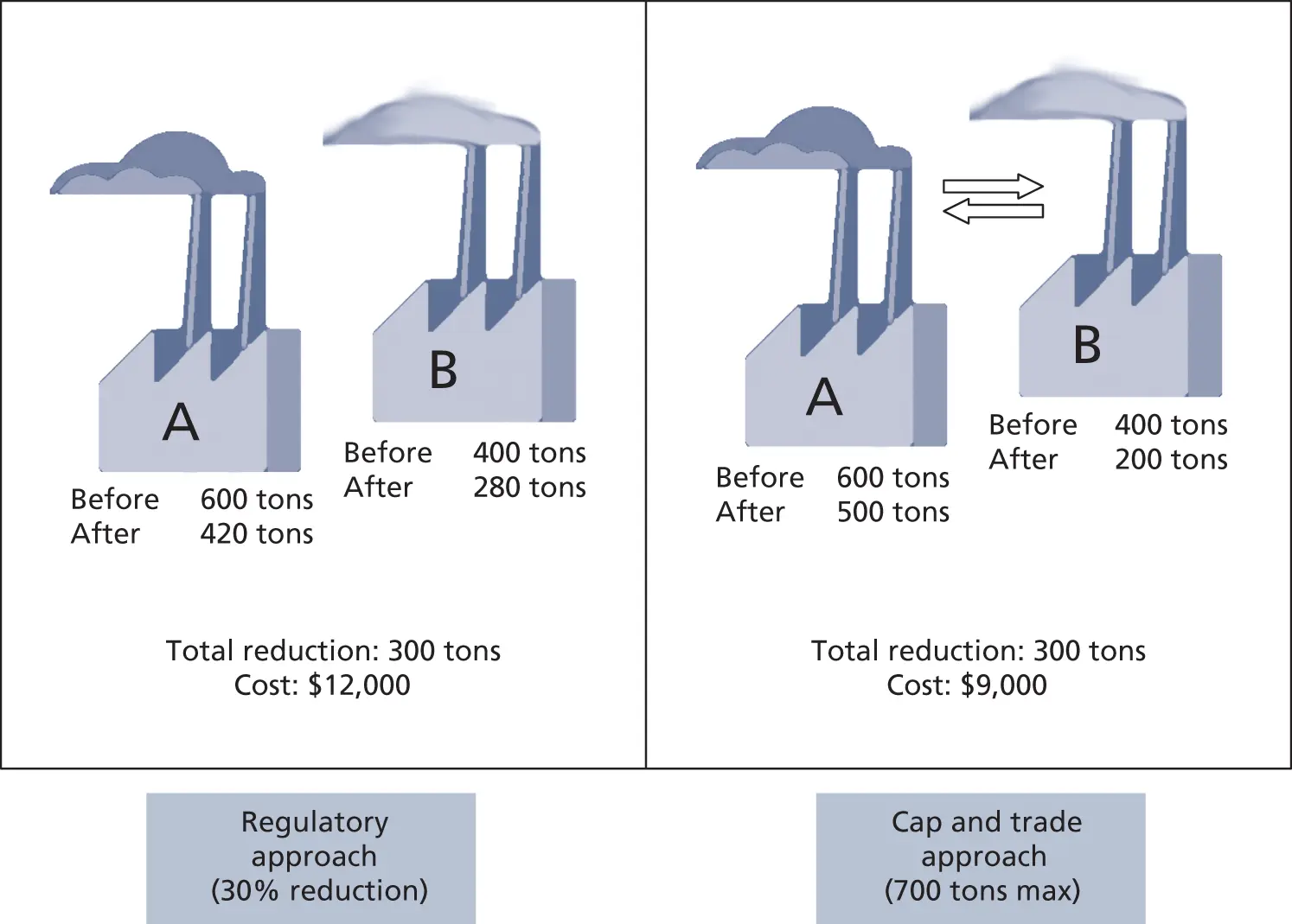

As shown in Figure 3.3, regulation can be used to reduce emissions in an industrial setting by demanding a 30% cut in tons of pollutants for both factories A and B, resulting in a total removal of 300 tons of pollution from the atmosphere, leaving 700 tons overall. Significantly, however, Factory B, owing to its technology and system of production, can eliminate pollution at a cost of $25 per ton, while the older Factory A requires $50 per ton invested to do the same. Rather than spending an overall total of $12 000 to reduce pollution, therefore, it would be more efficient to simply cap the total amount of pollution at 700 total tons and allow the two firms to trade permits if they desire. In that case, Factory A might make some reductions of its own, but purchase the remainder of pollution credits from the more efficient Factory B, whose aggressive reductions result in meeting the net target. Both systems then result in the same amount of pollution reduction, but cap and trade does so more efficiently.

Figure 3.3 Regulation versus cap and trade. Both approaches result in net desired pollution reduction, but the cap-and-trade approach is theoretically cheaper overall.

The basic idea is that firms who are able to reduce emissions more cheaply (because of available technology, know-how, or experience) can do so for other firms who are less able, and then be paid for the trouble. The US SO 2“Acid Rain” trading system began in 1995 and reports significant emissions reduction. Proponents claim that the trading system yielded 30% more reductions than non-flexible methods, where every factory had to meet the exact same requirements. Even where operational costs increase somewhat, this provides new incentives to innovate cleaner production and tranportation. Consider the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), which is boldly predicted to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the shipping sector by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels ( https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport/shipping_en).

Читать дальше